As I sit down at Joshua’s Cafe in Woodstock with Eisner Award-winning artist Ramona Fradon, 91, I can see her sizing up our surroundings. The small, gray-haired comics legend is dressed in the relaxed, Bohemian-looking layers favored by Hudson Valley residents, but her eyes are on high alert, watching the patrons and passersby. As a server pours water, she clocks three women in maxi dresses standing outside, settling their lunch plans. “Wherever you go in Woodstock,” Fradon tells me with a conspiratorial smirk, “you see clusters of women talking intently.”

Fradon couldn’t be nicer, but she has the canniness of a woman who survived the some of the nation’s hardest decades — and the pressures of an all-male industry — by her own wits. I confess to her that I’m only a casual comics reader; my husband is the one with a passion for superhero stories. “Could you explain that to me?” she asks with a smile. “I just do not understand the grown men who are so into comics.”

It’s not that Fradon doesn’t appreciate her fans. The artist, who drew DC’s Aquaman for most of the 1950s, enjoys appearing at conventions (though of late, she’ll only attend those in driving distance of her Catskills home). She gets a kick out of the occasional hyperspecific commission request, like the person who asked her to draw Batman, Plastic Man, and Aquaman at a family barbeque. And she’s proud of her work for Marvel and DC, which includes original creations like shape-shifter Metamorpho, superhero team the Elementals, and Aquaman’s mother Atlanna. It’s just — when she started drawing superhero comics in 1951, she never imagined that her work would have an audience over the age of 10, let alone that one of her characters would be played by Nicole Kidman in a $160 million motion picture.

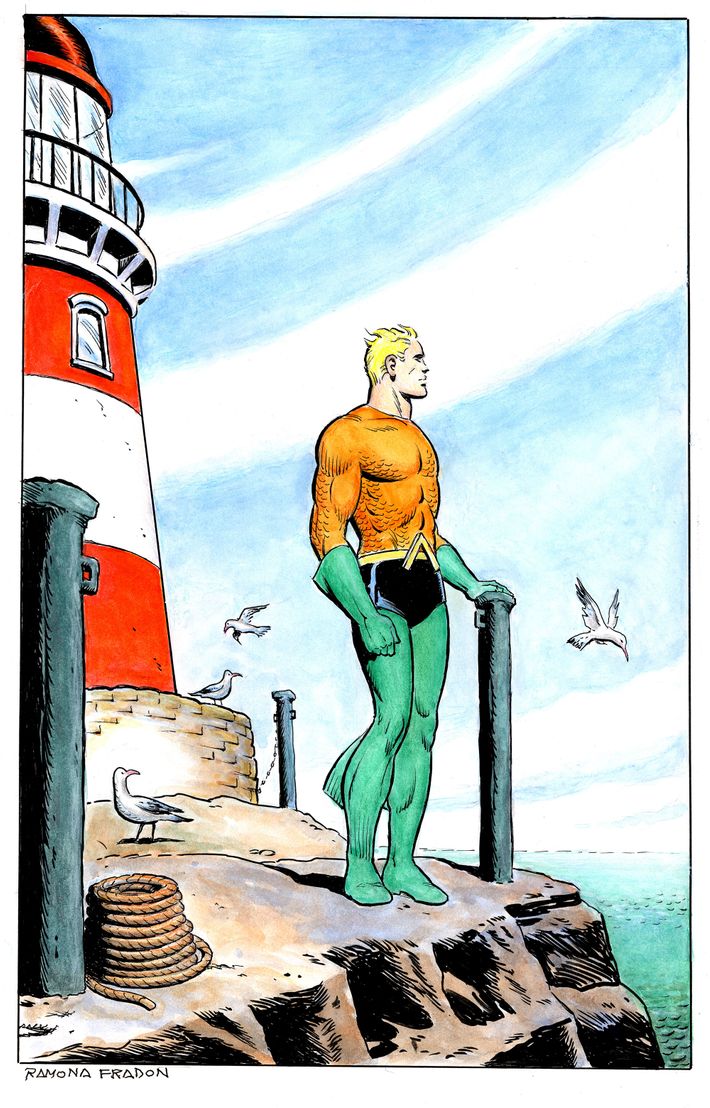

But Fradon also knows, perhaps better than anyone, how quickly and dramatically the comics industry can change. “Aquaman is a good marker of what’s happened,” she tells me over the restaurant’s famous zucchini fritters. “When I was drawing him back in the ’50s, he was nice and wholesome, with a nice haircut and pink cheeks. Very handsome. I had a crush on him. And you can see what happened to him! It got more and more violent, and then he lost his hand, then he had a beard and he looked psychotic.” She laughs. “You know what? I don’t get it.”

Fradon drew Aquaman like a ’50s matinee idol seen through soft-focus saltwater. “Some people have accused me of making him look gay, but I don’t think he looks gay,” she says with a shrug. “He’s just good-looking.” In fact, Silver Age Aquaman resembles Troy Donahue or young Burt Lancaster, but chiseled like Rock Hudson with eyes like Paul Newman. For decades, this clean-cut, tights-wearing blonde is what DC comics readers, and anyone who watched the Super Friends cartoon, pictured when they heard the name “Aquaman.” That began to change last year, when the DC Extended Universe introduced its big-screen sea king, played by Jason Momoa. If Fradon’s Aquaman was the perfect mid-century star, Momoa is everything a millennial could wish for: tattooed and caramel-skinned, with soulful eyes, sculpted abs, and hair that’s begging to be pulled into a man-bun. The star of this December’s Aquaman is a new century’s model of superhuman beauty.

Born in 1926, Fradon is several generations removed from Aquaman’s target audience. When she started drawing the character for DC Comics, she and then-husband Dana Fradon (who later became a New Yorker cartoonist) were among the many young couples struggling to make ends meet in post–WWII New York City. An art school graduate with no particular career ambitions, Fradon left her cold-water flat on 14th Street and began knocking on the doors of comics publishers. “I made up some samples and got jobs everywhere I went,” she says, still surprised at her luck. “Later on, I heard it wasn’t that easy to do! I guess I was just destined to be a cartoonist.”

It was a while before Fradon realized that there were virtually no other female artists in the 1950s comics industry. “There were two of us,” she says, referring to colorist Marie Severin, who worked primarily for EC and Marvel. “As soon as I got up to DC, people started asking me if I knew Marie, because she was, you know, the only other one.” Severin passed away in August (shortly after this interview) and oddly enough, the two women didn’t meet until a 1995 event at San Diego Comic-Con. “I’m sorry I didn’t know her all those years,” Fradon says regretfully. “We would have had a lot of fun together.”

Although she’s heard the stories of gender discrimination in the comics industry, Fradon says she was rarely treated differently than the male artists. “There was one jerk who used to come up behind me and kiss me on the neck,” she recalls. “But that was it.” She also steered clear of the testosterone pileup that was the DC bullpen. “I used to get in around 3 in the afternoon when they were all going a little crazy from doing all the comics, and they began to throw all these ethnic jokes around, and erasers and things would fly through the air, and I thought, My God, if they see me I’m finished,” she says with a laugh. “So I would creep in the back and put the drawing board up, so they wouldn’t see me. I mean, I was scared. And I was shy.”

Then, in 1959, Fradon encountered a career obstacle that most of her colleagues would never face: She became pregnant. Per the convention of the day, she retired to Connecticut after having her daughter Amy. “I just became a suburban mom. You know, I drove Amy everywhere, threw dinner parties, all that,” she says. Eventually, she found herself “feeling kind of trapped, because I wasn’t working and I was just being a chauffeur.” She wrote a children’s book, The Dinosaur That Got Tired of Being Extinct (finally published in 2012), about a fossil who breaks out of a museum to find some friends. “I was expressing my feelings, I guess,” she says with a satisfied smile.

In 1963, Fradon got a call from a DC Comics editor who wanted her to create a new character: the experimental, shape-shifting superhero Metamorpho. Intrigued by the challenge, she worked on Metamorpho between those school pick-ups and dinner parties. In 1973 she returned full-time to DC — and was astonished at all the changes that had taken place in her absence.

“Up at DC when I was there in the ’50s, it was very staid. You had hallways and office doors, and the office was relatively small. There would always be a file cabinet and a desk or two. And that was it. Very simple. And the men all wore suits and ties and sat behind the desks,” she says. “And then when I came back in the early ’70s, it was just like a bomb had dropped. There were no offices, it was all cubicles, and there were cartoonists in there somewhere, but there were papers and coffee cups and just complete chaos.”

The comics had changed too; they were less rigidly scripted, more violent, occasionally political. Readers now preferred Stan Lee’s conflicted, superpowered teens to the godlike heroes of DC. And there would be another major shift when Superman opened in theaters in 1978. “That changed everything,” she says. “They reached a whole new audience and then started writing for that audience.” As far as Fradon is concerned, the appeal of the best superhero characters — and “DC has by far the best characters,” she declares matter-of-factly — lies in their simplicity, the “mythic quality” that distinguishes them from the humans they’re sworn to save. By giving them ordinary faults and insecurities, both the modern comics industry and Hollywood have cut down the godlike heroes in a way that Fradon finds unappealing. “They decided to psychoanalyze the superheroes,” she says. “And to me, that ruins it.”

Throughout all this, Fradon’s work remained in demand. It’s not hard to see why. After lunch, we drive to her family’s house, one of those old Catskill homes that looks like it grew from the side of the mountain. There she shows me piles of sketches, mostly copies of recent commissions. Every pencil line is clean and full of energy. Perhaps owing to that art school education, her sense of composition is flawless. Her heroes, by design, are all just a little more perfect than ordinary humans, more symmetrical, their perfectly arched feet and balletic arms suggesting graceful movements across the page. Even when the characters are still, there is a sense of kinetic energy. You can practically see them breathing.

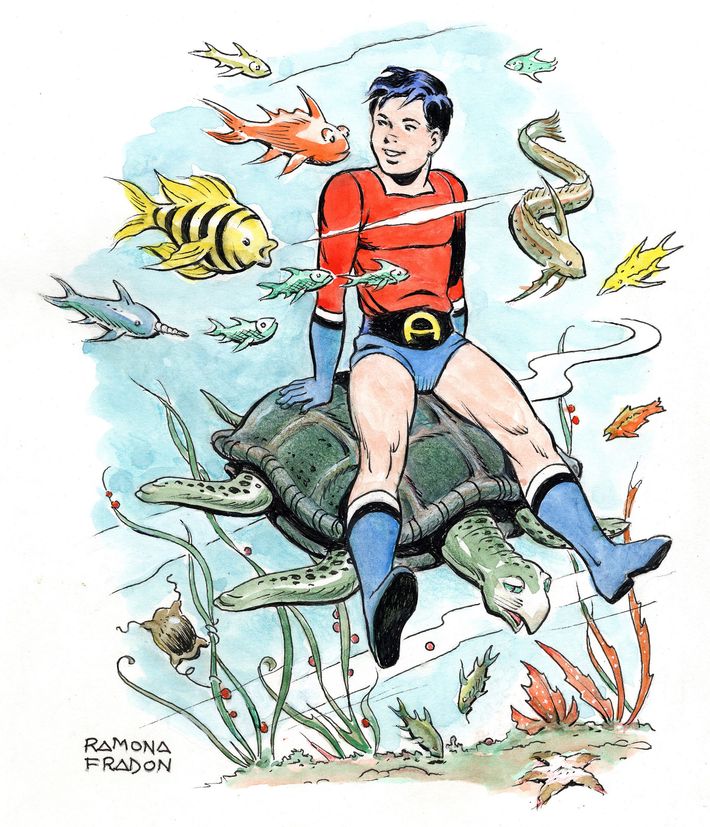

Drawings of Aquaman are her most requested fan commissions. (She actively accepts these via the Catskill Comics website.) In one of the pages she shows me, he’s riding on a dolphin; in another, a seahorse. In one drawing, he gazes down at his undersea kingdom like Ozymandias before the fall. “This is my favorite one,” she tells me, pulling out a beautifully shaded sketch of Aquaman swimming with a sea turtle and a school of exotic fish. I tell her I love her undersea creatures.

“I made up a lot of them,” she admits. “Because you know, I figure there’s so much variety under the sea that if I make it up, I’m liable to hit on one that’s right.” It’s clear that she finds a certain joy and artistic freedom in making art for fans — which is why she’s still doing it, more than 20 years after her official retirement in 1995.

I ask if she’d like to see the Aquaman trailer. She’s skeptical; she hasn’t seen a superhero movie since Superman, and she doesn’t think she’s missing out. But within a few seconds of my loading the video, she’s smiling ear-to-ear.

“This looks like fun. It does!” she exclaims. But, she adds of Momoa, “He should be blond.”

This article originally misidentified the dates of Ramona Fradon’s pregnancy and Metamorpho creation. It has since been corrected.