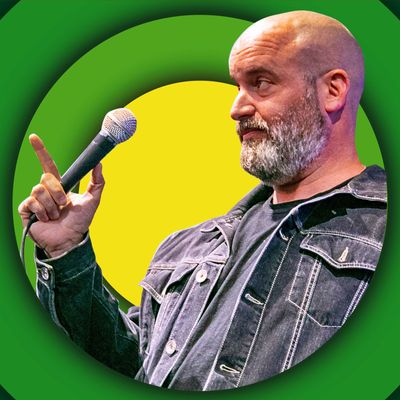

Ever since he was young, Tom Segura has liked to disgust people he cared about. Finding the boundaries between what would get his mom to roll her eyes and what would get him in trouble was how he played. Now that four Netflix specials have made him one of the biggest touring acts in the country, he has turned this sensibility on his fans, especially the white ones. Like when he starts a joke on his 2016 special, Mostly Stories, by appearing to sympathize with how hard white guys have it these days (Segura’s father was a white American, his mother a darker-skinned white Peruvian), only to turn it back on the part of the audience who cheered along.

On Good One, Segura talks about how to tell a story, messing with his audience, and how he developed his outsider’s perspective. You can listen to the full episode below and tune in to Good One every Thursday wherever you get your podcasts.

Good One

Subscribe on:

I want to talk about your experience of whiteness. Your mother is Peruvian, but you always call yourself white. You moved a lot but spent summers in Peru. Do you feel like you have an outsider’s perspective on whiteness?

I actually get to experience the world through two lenses. People who know me know I have this Latin side. They always introduce me as Spanish: “This is Tom, he’s Spanish.” Some of them see that as a huge benefit, but why? They say, “You have this diversity that no one can see but we know is inside.” Which I understand. I get it. I’ve been able to navigate the world in the easiest way, like a white male. Super-easy.

But it’s funny because we used to have to tell my mother, “You’re not white.” And she’d say, “What are you talking about?” She would probably put down “Hispanic” or whatever, but when she goes to Peru she’s considered white. Here, she’s not. She has an olive complexion to her and an accent. My father was super white — a white, white American guy. I’ve seen people treat my mother differently from him. These are things you never think about, but it doesn’t register to you until you’re actually witnessing it. It’s very sobering in the moment — snaps you right out of it.

That’s why I ask. Because this joke has both the perspective of being a white guy and the perspective of seeing how white guys act with white guys and being like, I’m not like that.

I do feel like I’m not that white guy. I get that I’m white. People will say, “You present white.” And I totally get that. I also feel like there’s a different group of white guys that are white-white guys and, yeah, I’m not them. Those dudes are a separate class from me. I have too much flavor in my background to be like that. When I went to college, the white-white southern dudes were pledging fraternities, and that’s like the highest form of white kid. I remember thinking, I’m not in that category.

Do you feel like those experiences have affected how comfortable you feel addressing race in your act?

I just feel like it’s part of life. It’s like how I talk about my kids a lot now. If you have kids, it’s weird to not talk about them. Race is universal. It’s part of our history. It’s part of everyday life. Why would I not talk about it?

A few years ago it was announced that you were going to do a bilingual special. Are you still going to do that?

I don’t think so. I got the offer to do it, and we had set up a tour. When I do an English special, I have to run that hour fucking 150, 200 times. That’s what it deserves. And I wanted to run this thing in Spanish, if I can, at least 50 times, right? The tour was all set to go — starting in February of 2020. I was able to do a couple shows in March and April at places that stayed open during the pandemic. But as things progressed, most of the tour couldn’t happen.

Is doing a bilingual special at some point important to you?

I was really excited about it at the time. I was missing how close I used to be with my mother’s side of the family, my Latin family. I would spend so much time there as a kid, and then my cousins would spend so much time in the States. They would come to school with us, and we would go with them. That part of my life was really important, and I got excited about it being united. I started doing the podcast in Spanish. I started doing these shows in Spanish. I’m hanging out with Latin people all the time, going on the road with them. And it was very fun. It was really exciting to have that back, to feel closer to that side of my roots. But you can’t predict a global pandemic. But I would love to do a bilingual special. I’ve always wanted to do something in Spanish as an actor, as a comedian, as something. So I hope I get to do it at some point.

You start Mostly Stories by saying, “If you’re white, do you ever get tired for being blamed for every racial injustice?” There’s part of the audience that starts cheering, and then you turn it back on them. Is that a piece of it — to find the people in your audience who might be “that white guy”?

Yes. And I just remembered I have a huge racial thing that I forgot that I’m doing right now. I don’t want to give it away, but it is the most that type of thing that I’ve done. It is so fun to trick somebody into revealing who they are. You hear a hint of a prejudice — what are you going to do? What I’ll do is be like, “Yeah, I know what you’re saying.” And then you let them show you know who they are. When people cheer at the wrong stuff, it’s very fun.

Do you think about what they thought of the show? Do you imagine them going home thinking, Tom sucks. I thought he was a guy like me?

Oh, no, I don’t care. Sometimes it’s somebody who gets very mad about the fact that I’m mocking them for something terrible. And I don’t care if that person is like, I hate Tom now.

On your podcast you say you love to see people aghast, which I thought was really funny way of putting it. Is that what you’re going for when you’re performing and you’re doing a joke that you know might make the audience recoil?

It makes me feel warm. I love that.

Your book talks a little bit about how the name of your 2018 Netflix special, Disgraceful, is a reference to your mom and sort of things that she would say about you and your material. Does making the audience recoil feel like love?

My mom is a traditional South American woman, super Catholic old-school conservative. She finds me funny but absolutely disgusting. And I could not enjoy that more. It is the greatest joy for me to see her upset about my act. I’m really going to miss her when she dies because she really, really makes me laugh at that stuff. To get somebody to gasp and laugh, or drop their head and laugh, there’s something like that in that moment that feels very much like love.

In the past few years, especially post-Trump, certain comedians have given their specials edgy names like Triggered and spent a lot of their act bragging about they’re so edgy and so challenging to an audience that seems very excited to hear them. I think of these comedians as Bad Little Boys more than anything else, but I feel like you avoid that. You’re right up to what those people are trying to do, but you’re not indulging it, you’re not self-satisfied. Is it intentional?

In comedy, when you hear a certain premise or topic addressed, you’re like, It’s been covered. So I really do try to stick to my jokes, my observations, my stories. I try to get fuel for everything I’m saying from what’s actually happening, that’s observationally unique to me. That whole self-satisfied thing, I’ve seen it too. I had my own touch into it five or six years ago: You can’t say these words. But you can say all of those things. What happens is that everybody’s going to yell at you, and maybe that’s not going to be enjoyable. But the reality is you can definitely still say the wildest shit. It’s just that people are going to fucking scream about it. And that’s the new part.

This interview excerpt has been condensed and edited.

More From This Series

- How to Turn a Comedy Podcast Into a Comedy Documentary

- This Is Judd

- Ramy Youssef on the First Israel-Palestine Joke He Wrote After 10/7