Disappointingly in some ways, Danai Gurira does not show up to meet me on Macdougal Street leading a pair of armless zombies on leashes, their jaws hacked off for safety. That’s how she first appeared, a hooded savior in the postapocalyptic Georgia woods, to the millions of hungry fans of The Walking Dead, which returns in October for its fourth season. In fact, a few wandering packs of disoriented tourists aside, it couldn’t be a less apocalyptic late-summer day. Everything is bright and pleasant, including Gurira, who doesn’t come off nearly as tough as her TV character Michonne, a wary, truth-telling, katana-sword-wielding badass who has been known to spit out her lines while simultaneously doing crunches.

Over lunch, Gurira shows me photos on her iPhone of fan tributes to Michonne: “This is someone who I guess created a ‘Single Ladies’ thing out of me and my zombies. It’s hilarious.” There are viewer-made T-shirts for an imaginary Michonne self-defense school, and a creepy homemade version of something gross her character does in the show: spell out go back in zombie body parts. “Then this is the fan who tattooed me on his shin. That was a little scary … I’m like, ‘Guys, if I go missing …’ ”

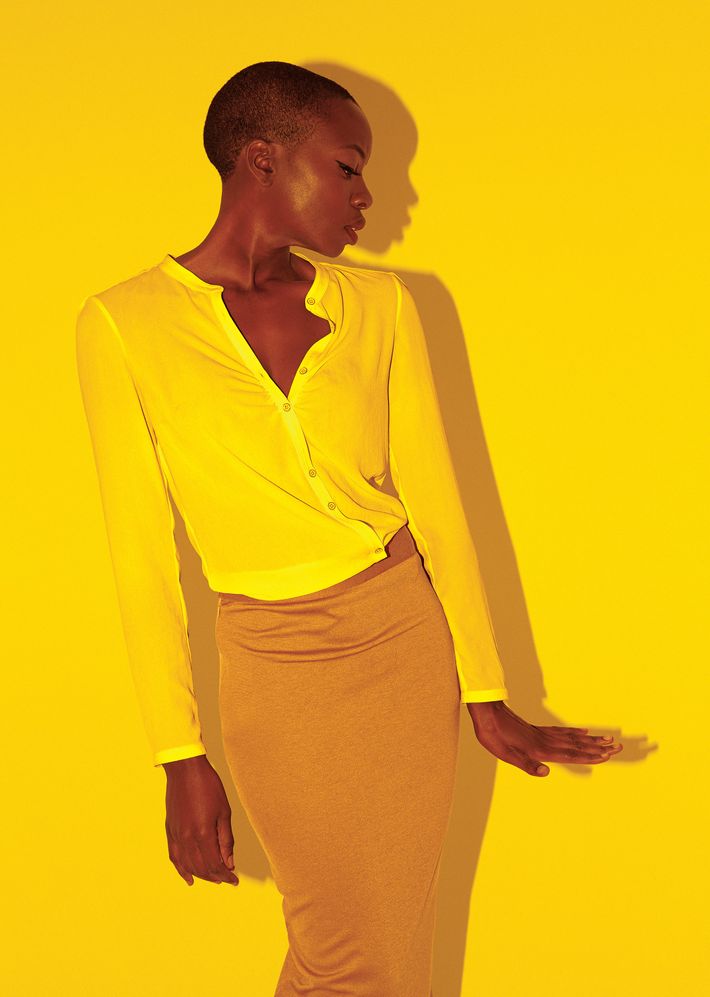

Gurira, 35, is trim and precisely presented: She’s wearing jewelry from South Africa and her native Zimbabwe; her shirt is by Suno, a brand inspired by the traditional prints of Kenya. Her parents, like Obama’s father (as she points out), came to the United States in the sixties to get graduate degrees, returning to Zimbabwe when she was 5 to work at a university there. She moved back to the U.S. for college, and her family members later returned too. It was in Africa that she first started acting, imitating Dynasty’s Alexis Colby in her backyard—not that she was inspired to emulate Joan Collins’s Machiavellian socialite, but it was what was on TV at the time.

Many of the roles Gurira’s done since then, like the 2007 film The Visitor, in which she plays a Senegalese jewelry designer and illegal immigrant in New York City, are carefully chosen to have different stakes than those that emerged from Aaron Spelling’s glitter-soap imagination. Gurira has written some of them, too. Her first play, In the Continuum, which she co-wrote while studying acting at NYU’s Tisch School, was about two women, one in Africa and one in the United States, confronting an HIV diagnosis. It won an Obie in 2006 and has been widely produced. And even while she’s de-braining the undead on basic cable—not to mention being swarmed at Comic-Con—she has two other plays being workshopped this year.

Gurira is also the lead in Mother of George, an entrancingly indirect film by Nigerian-American director Andrew Dosunmu that comes out this week. Her character, Adenike, moves to Crown Heights from Africa to wed her longtime long-distance fiancé, who owns a restaurant there. It’s a muffled, hermetic film about family expectations in an immigrant community, and every shot is artfully framed—often off center, through a window, doorway, or curtain, as if avoiding looking you right in the eye. For Adenike, “I always thought they were going to go to Nigeria and pluck out a girl who’d never acted in her life,” Gurira says, and in fact she is so demure in her depiction that you forget she’s inhabited any other role; Michonne (much less Alexis Colby) is the last person on your mind.

Mother of George is the second film Gurira has made with Dosunmu, a fashion photographer. She had a small role in 2011’s Restless City; the whole team behind it, from the costume designer to the director of photography, became her “family,” she says: “A family of people who are working to tell African stories” that are “on the ground,” based on actual experiences.

“The thing I’m against is the inauthentic portrayal of Africans,” Gurira says—roles in which she’s supposed to play a woman who’s waiting for her husband to bring her home a fish, for example. “I’m like, African women don’t wait for men to bring them home fish. They go and plow the fucking land and make their own food. You don’t know what the hell you’re talking about. I’m not doing that. There are tons of things that I turn down based on the fact that this portrayal of the African woman is so pathetic.”

Given how thoughtfully Gurira vets her other roles, Michonne might seem like an avatar out of a video game; The Walking Dead’s source material is a graphic novel, and at times it can feel like survivalist, first-person-shooter fantasia. I ask Gurira whether she worries Michonne is too much of a comic-book character—the tough, butch-sexy, fatally decisive black girl with the dramatic dreads.

“She wasn’t cartoonish to me at all,” she says. “The rage in her is connected to the trauma of women in war. I read the comic book after I got the job, and other than just seeing how they drew her eyes, I wasn’t looking at it.”

For Gurira, her approach to the role was based on her research for a play. She’d been studying Liberian women rebel soldiers she’d read about in the New York Times in 2003, who’d become a formidable force. “I had been to Liberia, and it had became a horror show, because the rules were gone, the structures were gone. It was a free-for-all.” And these women she read about, “they were fierce, and they were African, and they had AK-47s, and they had cute little outfits on at the same time, and they were really scary chicks. When I saw The Walking Dead and I started to read about the show, I said, ‘Oh, she’s one of them chicks.’ ” So this is where Michonne is coming from: stylish self-preservation. “It might make you someone who’s not willing to be messed with. It might make you someone who lashes out in order to protect yourself, because you know what has happened to you and what you’re never going to let happen again.”

What is often so great about Gurira’s Michonne is that she seems like she’s lived through something impossibly horrible. The show at its best is a tour de force of PTSD, helping elevate it beyond the typical horror-movie unspooling of who-will-die-next. It asks the question, Gurira says, “Who will you become? You won’t be who you are today, I promise you that.”

The funny thing is, as popular as Michonne is, fans keep telling Gurira they wish she were more vulnerable. “She’s had vulnerable moments, but I always wonder, Do you want her to walk around crying all the time?”

They also want her to hook up with the male lead of her band of still-human survivors, Rick. In other words, they hope for a happy ending to the end of the world.

This is what any TV star would want: to be beloved, to give people what they expect, what they’ve been given before. And Gurira is eager to satisfy her fans. Her TV popularity will get the word out about Mother of George, and it gives her the time and pull to help her get her plays produced. There’s still more fighting to do for her as well as Michonne. “At the end of the day, she feels herself as a warrior.”

*This article originally appeared in the September 16, 2013 issue of New York Magazine.