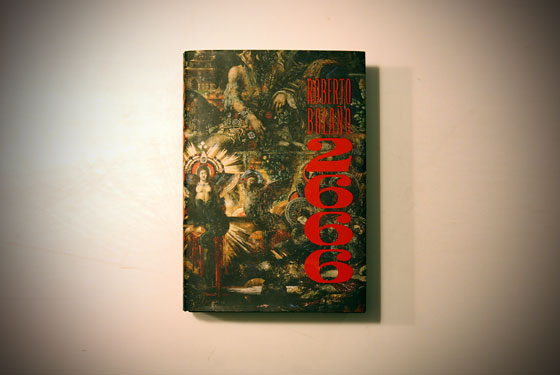

Any reader currently having orgasms over Roberto Bolaño novels in English should throw a mental bouquet to Natasha Wimmer, who spent the last several years translating his two biggest and most style-heavy books, The Savage Detectives and 2666. Bolaño puts extra stress on translation: His Spanish ranges from journalistic detachment to poetic theory to filthy Mexican street slang; his characters include literary critics, German soldiers, Mexican cops, and an African-American reporter from Harlem. We asked Alan Page, translator of the screenplays 21 Grams and Babel, to find out how Wimmer did it.

Given that it’s never referenced in the book, what’s your interpretation of the book’s title?

It’s equal parts ominous and obscure. It contains the number of the beast, but it also designates a year so far in the future that it recedes from view. To me, it signifies remote, incomprehensible malevolence.

What would you say makes for an English that is “Bolañesco”?

Many of the same things that make for Bolañesco Spanish: extravagant metaphors, deadpan non sequiturs, heterogeneous sentences, an underlying plainness.

After your work on the Savage Detectives, did 2666 come easily, or did you find new resistances?

I wouldn’t say it came easily, but it did come more easily. Partly because I had the benefit of experience, but partly because of the nature of 2666. Despite the subject matter, 2666 is cooler in tone and more formal than The Savage Detectives. The section I was most worried about — “The Part About the Crimes” — actually wasn’t too bad. “The Part About Fate” was easily the trickiest — try channeling an African-American narrator as imagined by a transplanted Chilean who never set foot in the United States.

Reading Bolaño in Mexico, one is struck by the force of the narrator’s Mexican Spanish. It’s direct to the point of seeming almost like a kind of neutral reportage, but at the same time, the voice feels authoritatively Mexican. How did the narrator’s “Mexican” affect the cadence or tone of your narrator’s English?

The voice might be Mexican, but the language generally wasn’t — or at least not as slangily as in parts of The Savage Detectives. My sense of Bolaño’s Spanish is that it is a real blend. He lived in Spain for the last twenty-some years of his life, and I think you can feel the influence of Castilian Spanish at least as strongly as Mexican Spanish.

There are a range of different tones and “Spanishes” coming from so many characters. How do you go about ventriloquising a master ventriloquist?

Mostly I just try to follow Bolaño’s lead — which sounds like a cop-out but is the truth. I did do a fair bit of forensic science research for “The Part About the Crimes,” because Bolaño gets quite technical. “The Part About the Critics” is satirical and cerebral; “The Part About Archimboldi” is epic but also often whimsical; “The Part About Amalfitano,” which I love, is tender and urgent and lyrical. Anyway, those were the registers I sensed and tried to capture.

Were there any voices that were particularly resistant to translation? Why?

Florita, the TV seer who has visions of the women killed in Santa Teresa. Florita’s speech is folksy, which I always find difficult, and her syntax was also tricky — she speaks in endless sentences. The Fate section in general was full of difficulties: the boxing scenes, Barry Seaman’s talk, Fate himself. Part of the problem is that there are so many levels of reference, from hard-boiled crime fiction to postmodern horror.

The young Archimboldi’s dialect, which is based on puns — how did you go about transferring Spanish puns (spoken by a German character) into English?

Is it really puns? I just looked back over the dialogue, and I’m not sure what you mean. You strike fear into me! Missing things like that is the translator’s great dread, but it’s probably inevitable occasionally, especially with Bolaño.

What was your experience of translating the ex–Black Panther’s ten-page monologue?

To be frank, lots of back and forth with my editor, Lorin Stein, whose counsel was invaluable here and elsewhere. I reworked this section more thoroughly than most, trying to triangulate between the Spanish and the language a U.S. reader might expect an ex–Black Panther — and barbecue master — to speak. Bolaño’s cues here are ambiguous. I tried to capture that eccentricity with some slightly folksy, again, American English, but I didn’t want to take it too far.

As any translator will tell you, it’s quite an experience to live for a protracted period of time with a half-foreign, half-appropriated voice coursing through your head. How has it affected you?

What I remember better is how I felt after the first time I read The Savage Detectives, which was euphoric and full of the uneven, lyrical beauty of Bolaño’s sentences, which seemed to perfectly mirror their content. Like all great books, it altered the shape of things around me for days after I read it.

Are there any other great Spanish-language authors that you think should be known more widely in English?

Horacio Castellanos Moya’s Senselessness, published last year in English by New Directions, is about a writer who takes a job as the copy editor of a report on mass killings in Central America, and it’s a tour de force of paranoid humor. I loved the irreverence.

Related: Prose Poem [NYM]

The Bolaño Industry [NYM]