Around the midpoint of The Motherf**ker with the Hat — the highly entertaining yet frustratingly evanescent new black comedy from verbal pugilist Stephen Adly Guirgis — Jackie (Bobby Cannavale) lays out the play’s major point of debate: “Even though we’re fucked up, we got a code. It’s a fucked up code, but still, it’s a code.” Jackie, like everyone else in Motherfucker, is an addict. He’s recently paroled and in AA, a selective and unpredictable romantic, a sometimes womanizer and always self-pitier, with a less-than-dependable co-dependent in Veronica (Elizabeth Rodriguez), his high-school sweetheart and longtime squeeze, and, on her own, a highly accomplished drug abuser. Jackie puts himself in the hands of his sponsor, Ralph D. (Chris Rock), a man he trusts implicitly, a man who has all the answers — including answers to questions that Jackie, in his behind-the-curve naïveté, hasn’t thought to ask. (These include: Who’s been sleeping with my girlfriend? And: Might it be someone I trust implicitly? Someone who has all the answers?) Needless to say, “the code,” such as it is, is broken over and over, and its very existence thrown into irretrievable doubt. “You fake AA motherfuckers make me sick,” spits Veronica. “Y’all all the time preaching honesty and selflessness, meanwhile y’all more dishonest and selfish than half of C block at fuckin’ Rikers.”

In a good Guirgis play (and my favorite is The Last Days of Judas Iscariot, overstuffed and Wiki-stubbed as it was), there’s always some glimmering, bobbing moral buoy that recedes but never vanishes as the bumptious, hair-trigger characters kick up waves of slangy chaos. Here, as Jackie faces off against a bottomless pit of moral relativism (“What are we, Europeans or some shit?”), the buoy goes under and, for the most part, stays there. But the play really doesn’t have the heft to earn the death of hope, nor does it have the stones or the seriousness to declare hope officially dead. Motherf**ker mainly concerns itself with a lot of big, mordant laughs (with Yul Vazquez, as Jackie’s slightly Aspie ex-sex-addict cousin Julio, walking away with the show’s chewy center). Jabbing exchanges like “I coulda fucked your wife the other night!” / “Shit, I coulda fucked your girl the other day — and I did!” land solidly in the audience’s breadbasket, yet overall, the play feels jumpy and scant. Anna D. Shapiro hops from laugh to laugh at such a workmanlike tempo, the characters sometimes feel on the verge of urban blue-collar caricature. Despite the monumental pain they feel, these people lack the savor we hear in Guirgis’s best stuff.

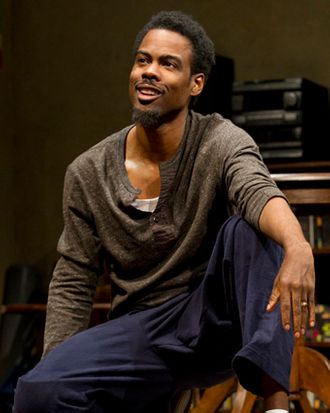

The fact that the play’s most dramatically consequential figure is also its most morally elusive probably doesn’t help; the fact that this character is played by a rather chilly, rather remote comedian helps even less. I’m not saying Rock isn’t funny: His specialties include flawless timing and devastating delivery, and on these scores, he delivers. He also manages a few impressively realist moments. But he’s just not a natural, and Ralph’s increasingly alien presence onstage — as his true motives are revealed — becomes a bit more alien than necessary. Ralph turns into a creature of pure irony, hardly the soul-sucking threat he’s purported to be. Instead he comes off as just another amusing character in a play that, by rights, should be his to haunt. We’re mightily relieved when Ralph’s long-suffering wife, played with alluring weariness and great authenticity by Annabella Sciorra, explains her life mate’s deep, weirdly impersonal, utterly rage-free misanthropy. Oh, we realize, so that’s who this guy is! Wow!

In fact, all of the most interesting insights into the motherfuckers of Motherf**ker emanate from adjoining characters, not from the mofos themselves. Cannavale’s Jackie, who spends most of the play dashing around trying to find himself, is a case in point: The stories cousin Julio tells about their childhood in Puerto Rican Morningside Heights are far more engaging than any case Jackie makes for himself. Cannavale controls the stage, but he’s pushing so hard, physically and vocally — the cords in his neck pulled bridle-tight at all times — he feels like he’s jockeying for a martyrdom when the character isn’t eligible for one. Jackie and Veronica, their profane and passionate glissandos, their arpeggiated hatreds notwithstanding, are no Frankie and Johnny. They’re not a couple for the ages, and the contest of their longtime love simply isn’t enough to keep Motherf**ker from drifting. For all they yack, for all we hear, we just don’t know them the way we should. As Jackie warns Ralph in the play’s payoff scene (which is, thanks to some awkward fight choreography, also somewhat anticlimactic): “Nobody knows nobody.” That may be even more true than the playwright intended.