Before saying why Lucian Freud, who died today, is the strangest case of my own personal artistic taste, let’s first remember a few things. It is difficult to imagine anyone in the profoundly homogenous, deeply tribal English art world of the mid-twentieth century, becoming as well-known and respected an artist as the German-born grandson of the founder of psychoanalysis, someone with the last name Freud. It’s like being a Plato, as unthinkable as a Rockefeller’s becoming a famous bohemian Abstract Expressionist in fifties America. As if the burden of a royal bloodline were not enough, few world-renowned artists strike me as having less inborn talent than Freud. His genius, such as it is, seems the direct result of someone willing himself to accomplishment.

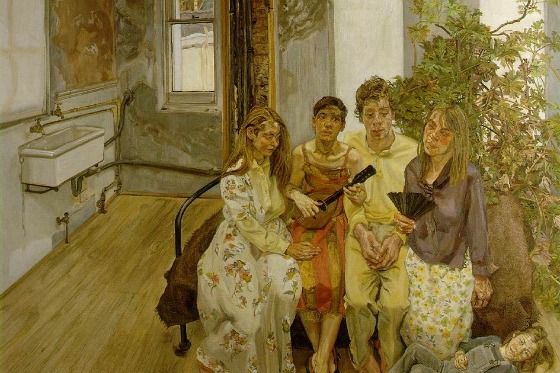

Which brings me to my personal taste. While I don’t particularly like Freud’s work (just last week I saw the Met’s current Freud show and thought, “Meh”). Yet then as now, I admire him greatly. I look at Freud’s intensely worked, eternally noodling oozey surfaces, the incessantly teeming little paint-brush strokes, the Morandi-like limited palette of flesh tones, and his claustrophobic vision of naked models forever posing in his famously dilapidated London studio, and am often struck by how the life of his art seems to drain away. Mostly what I see is nearly maniacal painterly control. Yet Freud is an important touchstone for the many of us who secretly fear that we are not naturally gifted; we who are not precocious geniuses, we non-Picassos who are always unsure that we even are what we say we are.

Thus I love Freud, even though I don’t love his work. Francis Bacon also came from moneyed roots, took his place in the cloistered English art world of the postwar years, and was a personal hero to Freud. But Bacon visibly struggled, labored, doubted. Although he made work that seemed to get into painterly ruts, he also had bursts of painterly exuberance, broke free of his repetition, arrived at highly original even revolutionary colors, and made stained surfaces that were as risky and flat Rothko’s. Freud, on the other hand, comes at you in the same ways every time; flesh for flesh’s sake; physical fervor; psychic frayed nerves.

There’s also the matter that, as an American, I may be prejudiced against Freud simply because he was so English. I often find myself privately stewing about much British art, thinking that except for their tremendous gardens, that the English are not primarily visual artists, and are, in nearly unsurpassable ways, literary. Yet this too connects to Freud, whose work—as admittedly visceral, gooey, and about “the flesh” as it is—is highly cerebral. For the longest time, Freud seemed a throwback, someone who addressed and battled School of Paris painting. As the world lurched away from French traditions, toward abstraction, pop, and beyond, Freud seemed to stand still.

Yet this is his salvation—and what makes him such an important artist to come to terms with. He is so dogmatic and insistent on doing what he does in spite of whatever trends come and go, while at the same time being world-famous and famously consistent, that his art now exists as a champion island in the mainstream for artists. Every artist will one day face the moment when he or she is doing what he or she does after the style has passed and the art-world heat-seeking machine has moved on. Lucian Freud’s career affirms that the only thing an artist can do is remain true to whatever vision, (lack of) talent, or ideas that happened to pick them in order to be made known to the world.