For a long time — probably too long — not enough people have thought about the far-reaching accomplishments of Helen Frankenthaler, foremost inventor in the fifties of what is variously called American Color Field painting and post-painterly abstraction. Whatever you call this short-lived movement, Frankenthaler used it to throw up an artistic bridge allowing artists to cross the blood-and-thunder-encumbered cosmos of Abstract Expressionism into a new world of Minimalism. Painter Morris Louis called her “a bridge between Pollock and what was possible.” Minimalist painter Kenneth Noland wrote, “We were interested in Pollock but could gain no lead from him. He was too personal. Frankenthaler showed us a way … to think about, and use color.” She did something else, too, although it’s even less obvious now. Frankenthaler may have been the first artist not regularly referred to, demeaned, neutralized, and made safe with the label “woman artist.” Before her, Frida Kahlo, Alice Neel, and Louise Nevelson regularly were relegated to the ghetto. Georgia O’Keeffe was said to feel “through the womb”; her paintings were a “revelation of the very essence of woman as Life Giver”; her “outpouring of sexual juices”; “loamy hungers of the flesh” were evidence of “one long, loud blast of sex, sex in youth, sex in adolescence, sex in maturity … sex bulging, sex tumescent, sex deflated.”

The sailing wasn’t easy. Frankenthaler was often belittled, her work called merely decorative. Critics said she made pretty wallpaper. Her marriage to A-list artist Robert Motherwell was often sniggered about, as was her five-year relationship with the critic Clement Greenberg. Charges of being a privileged rich girl were common, as were the laughably literal readings of her work, which said she was “about menstruation and the liquid world of the feminine.” Frankenthaler had to read dismissals of her work, often contrasting it with Pollock’s, like this: “Her work excites without quite satisfying … she can make a paint-mass spurt like a dike and yet control it till it laps the canvas like a spent wave.” Others fretted over the differences between ejaculation and menstruation. (Oy.) Yet Frankenthaler’s formal accomplishments somehow broke free of all of this.

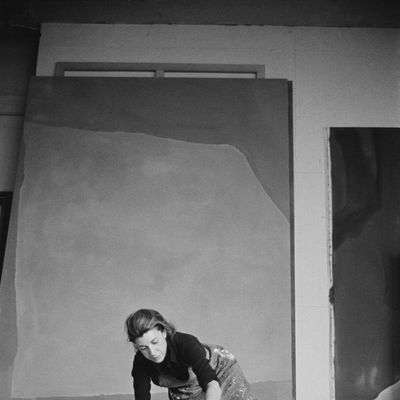

She blurred the borders between geometry, order, chaos, the body, atmosphere, and ground. She shunned the overemotional hysteria of Abstract Expressionism, pouring thinned, watered down, and turpentine-laden mixes of color directly onto raw canvas. Her structures and shapes were open, controlled by natural forces while also describing them. Her paint and canvass became one surface. This was a big deal back in the day. Edges evaporated; accident was visible; so were her means and intentions. Pooling paint created varying viscosities of thickness and thinness; paint dried into imagistic river beds, isolated islands, clouds, continental masses that all evoked landscape without depicting it or engaging any abstract sublime. There was no paint-flinging or implied dance around the canvas. There was picture-making, pure and simple. And beauty. Lots of it. Which of course made people run back to labels like feminine.

It’s easy to forget how radical it was for an artist to let go of structure, forsake known geometries, stop using the sides of the painting to define the image, move away from enclosed forms, and meld background and image, all while enthralling the eye, enticing the mind, and allowing others to use the work as a passage to a not-quite-known imaginary place. I think of artists as varied as Pipilotti Rist, Lynda Benglis, Albert Oehlen, Sigmar Polke, and Laura Owens catching glimpses of the possibilities in all this. I don’t think about Frankenthaler’s work often, but whenever I do, these things come rushing back into me.