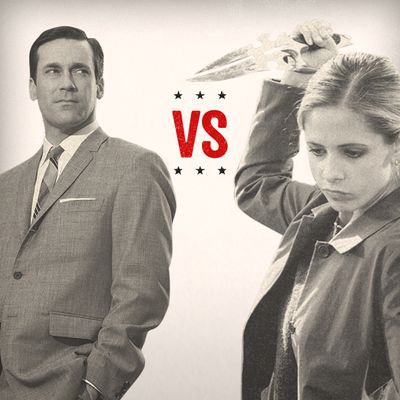

Vulture is holding the ultimate Drama Derby to determine the greatest TV drama of the past 25 years. Each day a different notable writer will be charged with determining the winner of a round of the bracket, until New York Magazine TV critic Matt Zoller Seitz judges the finals on March 23. Today’s battle: Playwright Stephen Karam judges Mad Men versus Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Make sure to head over to Facebook to vote in our Readers Bracket, where Vulture fans’ votes have already diverged from our judges’. We also invite tweeted opinions with the #dramaderby hashtag.

Buffy kicks ass. Literally. For seven years, her primary occupation was obliterating vampires, demons, and other forces of darkness with an astonishing array of flip-kicks, all with nary a blonde hair out of place. Plucky, sassy, and sexy, Buffy’s powers enabled her to destroy a demon in mid-air, land arms akimbo, and still have sufficient wind to deliver a game-ending, withering retort. Pitting a Slayer against any opponent seems unfair. But, as mere mortals go, Don Draper is a more than worthy opponent. While he isn’t adept at defeating the supernatural, the man has been busy battling his own personal demons during the first four seasons of Mad Men, also with nary a hair out of place. So let the (admittedly absurd) death match between Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Mad Men begin.

Despite their disparate genres — one show features a sexy woman who slays vampires; the other, a man who slays sexy women — both shows share key strengths and weaknesses. Chief among their joint assets is their ability to marry deft drama with rhythmically charged, unexpected comedy. Buffy’s comic chops are more readily apparent, and creator Joss Whedon unabashedly announces the camp factor in his show’s title and no doubt loses many adult viewers in the process. That’s a shame, because once you accept that Sunnydale, California, is located above the mouth of Hell, the show is more adept at capturing humanity than most naturalistic dramas.

That’s partly because Whedon knows the rocky road of adolescence can be a kind of hell on Earth, where every cruel joke and gym class has the potential to plunge you into the emotional abyss. The show sneakily uses the horror and teen genres to upend our expectations about both, painting an amusing and frequently poignant look at adolescent angst. Buffy and her friends struggle to connect with their parents, to fit in, and to find a date for the prom — all while struggling to prevent the apocalypse. It’s an ingenious concoction that works.

In its best moments, Buffy’s action-packed episodes are also packed full of surprising laughs thanks to Whedon’s silly-but-sharp wordplay. Take “Graduation Day, Part Two,” the show’s third-season finale, in which Buffy’s trusted friends Cordelia and Oz (a cheerleader and werewolf, respectively; just accept it) respond to her risky strategy to thwart the Mayor, who’s actually an evil demon determined to take over the world (again, accept):

Cordelia: I personally don’t think it’s possible to come up with a crazier plan.

Oz: We attack the Mayor with hummus.

(Pause as everyone takes this in.)

Cordelia: I stand corrected.

Or consider season five’s “Real Me,” in which Buffy learns an unlikable female vampire named Harmony has recruited followers in an attempt to kill her:

Buffy: Harmony has minions?

Xander: Yeah, that was pretty much my reaction.

Buffy: I’m sorry, I’m sorry, it’s just … Harmony has minions!

Xander: And Ruffles have ridges. Buffy, there’s actually a more serious side to all this.

Buffy: I sure hope so, ‘cause I’m having trouble breathing …

Buffy’s breakthrough badinage felt fresh because it effortlessly meshed top-notch teen-talk with matters more preternatural. (Buffy’s sister, Dawn, after witnessing her kill several demons: “I’m telling Mom you slayed in front of me.”)

Scoring a well-timed laugh in the midst of Sturm und Drang is one of Mad Men’s strengths as well. Note the economy and rhythm in office manager Joan’s hilarious reprimand upon learning that a fumbling new secretary, Sandy, has mishandled two crucial messages:

Joan: Sandra, everyone makes mistakes, but the fact that you’re the kind of person who cannot accept blame is egregious.

Sandy: I don’t know what that means.

Joan: It means I can’t believe I hired you.

Other times, the show radiates Wildean wit, its characters competing in a game of epigrammatic tennis:

Peggy: I know what men think of you: That you’re looking for a husband and you’re fun. And not in that order.

Joan: Peggy, this isn’t China. There’s no money in virginity.

For all of Mad Men’s laughs, creator Matthew Weiner takes the opposite tack from Whedon’s — he roots his show in drama, using a slick opening sequence to signal that “sexy seriousness” will be the prevailing tone. Dissonant chords announce the arrival of the now-iconic plummeting Hitchcockian man, a suicidal, suited silhouette. It’s all so damn beautiful. The entire show might very well work sans plot as a kind of period porn, a parade of curvaceous women, broad-shouldered men in impossibly tailored suits, original Rothkos on the walls, and Saarinen Tulip Desks. Some of the pleasure of watching Mad Men undeniably comes from the gray-green-taupe aesthetic; it’s like watching figures from a contemplative Hopper painting shake free of the canvas and come to life.

But after four seasons, it’s safe to say that the satisfying drama of Mad Men is the true secret to its success. The narrative joys are many: Pete Campbell’s rise from lowly account man to partner; Roger Sterling’s multiple falls from grace; Joan’s struggle to advance in a man’s world; hell, I’ve even enjoyed the journey of Joan’s creepy husband (known to those at Vulture as Dr. Rape) from medical resident to Vietnam soldier.

The most crucial story lines, however, belong to Peggy Olson and Don Draper, whose emotional journeys both climaxed beautifully in the show’s best episode to date, season four’s “The Suitcase.” Peggy is held captive in the office by Don, who fears being alone while awaiting imminent news of a dying friend. After Don has irrevocably ruined Peggy’s evening, the two of them, alone under the fluorescent lights of Sterling Cooper, trade breakdowns. The episode is quiet, unflashy, and stunning. Weiner gives us a chance to collectively catch our breaths and remember just how far these two have come. Peggy arrived as Don’s secretary and rose to become a valued creative employee and is now something even more — a confidant. Don and Peggy are hopelessly alone and inexorably linked.

Mad Men’s treatment of death has something in common with Buffy’s, as both series use the topic to motivate memorable drama (such as Anna Draper’s death in “The Suitcase”) as well as to land a quick laugh. In fact, for several-episode stretches on both shows, death can produce more punch lines than poignancy (i.e., on Mad Men, there’s Roger’s constant fatalism and Ida’s desktop death; on Buffy, apocalypse jokes are pretty much de rigueur). This is smart, because the moment death does cut close to home, it cuts deep. On Mad Men, the death of not only Anna, but also the fathers of both Betty and Pete proved affecting. And in one of Buffy’s best episodes, “The Body,” Whedon similarly pulls the rug out from under us. Buffy discovers her mother dead in her living room — not the victim of any supernatural forces, but rather of a brain hemorrhage. None of the one-liners we’d grown accustomed to arrive to make things better. The two-minute uninterrupted shot that charts Buffy’s discovery of her mother’s body — and the shaky 911 call and CPR attempt that follow — is devastating. Suddenly Buffy’s mom was, jarringly, just a body. The show didn’t spare its heroine the suffering of our earthly world simply because she’s fighting the demons of another.

For all their shared strengths, both shows have periodically gotten bogged down in backstory. Don Draper’s secret past (he stole his name/identity from a fallen comrade in Korea after going AWOL) is somehow never as interesting as the show’s creators think it is. Whenever the show zooms in on the who-is-the-real–Don Draper question for too long, I zone out; the show feels like it’s awkwardly merging with an episode of Lost or The Fugitive. Buffy committed a similar crime with its season-four decision to focus on the operations of “The Initiative,” an underground military organization in which commandos capture supernatural creatures to be studied by scientists for covert government operations. This time you don’t have to accept; the insertion of secret military operations into a show that was more Scooby Doo than NCIS caused the show to suffer a temporary identity crisis.

Mad Men also gets a demerit for its melodramatically pitched moments in which Don’s alluring bullshitlessness is betrayed by grandiloquent monologues. The worst offender was season one’s “Kodak Carousel speech,”* in which Don wins over his clients by talking for a really long time about Nostalgia. The pitch was written with such a heavy hand (and further underlined with manipulative music) that the moment unintentionally became less about Don’s genius and more about viewers wondering … wait, isn’t this the same music they used during Bob Saget’s lesson speeches at the end of every Full House episode?

Another forgivable fault is the arc of Don’s (now ex-) wife, Betty, whose depression became oppressive in the last season. While I have stopped thinking that January Jones is a lackluster actress and started to appreciate that her complete lack of affect has its own effect, there were nonetheless times in which I wanted to take this insufferably spoiled woman and lock her in a room with Buffy’s unforgiving Cordelia, who would serve her some useful advice: “Embrace the pain, spank your inner moppet, whatever, but get over it.” Even truthful despair can become banal if it isn’t periodically interrupted by hope. Then again, Buffy, like Betty, fell into a depression in season six (it’s complicated, but: Buffy died and was in heaven, but her friends brought her back to Earth via a powerful spell, and that was very hard for her — just allow it). Buffy’s gloom resulted in tedious plotlines even more problematic than those found in Mad Men, largely because Buffy, unlike Betty, is the show’s emotional glue. And in its seven-year run, Buffy occasionally suffered from something virtually unseen in Mad Men: bad acting. David Boreanaz (Angel) improved as the first season went on (he learned how to smolder in five ways instead of just two), but Buffy’s egregiously dull love interest Riley Finn was — to use a word coined by a friend — “borgeous.”

Buffy also lacks the overall narrative power of Mad Men. Where Buffy is quick to whip out new monsters and themed episodes each week to entertain, Mad Men is patient in its plotting. From the pilot right up until season four’s finale, Mad Men builds momentum so subtly you don’t even realize it’s happening. Weiner enables us to feel the slow passage of time via strategically placed narrative landmarks. (Lucky Strike was the first client we see Don handling, and the show took four full seasons to arrive at the dissolving of that client relationship.)

Buffy’s characters also have linear emotional journeys, of course, but the show often settles for an episode in which crafting an entertaining 48 minutes takes precedence over pushing individual characters’ plotlines forward. In fairness, being less structured allowed Whedon to fashion more unique episodes, such as the musical extravaganza “Once More With Feeling” (which is, to quote one objective YouTube commenter — “the best episode of anything ever”).

But Weiner’s patience is the more impressive skill, as is his ruthless editing. Mad Men could easily rely on padding its episodes with gratuitous nods to the sixties historical/sociological event-of-the-week. And yet, he consistently shows restraint (even when dealing with the death of JFK) and keeps his focus tightly on his characters.

Weiner’s ruthless editing is also evident in his ability to write beloved characters off the show. Buffy died twice in seven years, yet she always came back to life. Mad Men is unafraid to bid a firm adieu to those we love and love to hate (Sal, Joey, Lois, Ida, et al.); no one feels safe.

And even if the chief reason Mad Men has less fat and fewer wasted moments is thanks to its shorter seasons (Mad Men has twelve episodes versus Buffy’s 22), for me, the scales still tip firmly in Mad Men’s favor. Yet somehow choosing a winner between two distinct and deserving shows and two powerful adversaries still feels akin to deciding whether vanilla is officially better than chocolate.

So I thought about Buffy and Don’s primary strengths. Buffy consistently and reliably assails her opponents with physical force and witty repartee. Don’s battle tactics, however, are frighteningly unpredictable. This makes him far more dangerous. A particularly piercing example pops into mind: the way Don dealt with Jimmy Barrett’s wife. In the season two episode “The Benefactor,” Jimmy — a jerk comic starring in one of Don’s commercials — insults a firm client, leaving Don with the unenviable task of getting Jimmy to apologize. Predictably, he turns on his charm to win over Jimmy’s wife, Bobbie, who turns out to be a fearsome opponent in and of herself. She thinks she has Don outsmarted, and even celebrates her upper hand with a little blackmail:

Bobbie: I think an apology … has to be worth $25,000. Say it’s a bonus.

Then Don does the unthinkable: He grabs Bobbie, thrusts his hand under her dress, and — while his fingers are still seemingly deep inside her — gravely instructs:

Don: Believe me … I will ruin you. Do what I say.

Don’s dark side has proven to be, at times, pitch black, his character more coldblooded than any vampire. Buffy is a Slayer, but Don Draper is a lady-killer. An alluring, volatile character like Don in a superiorly plotted show yields superlative television. Mad Men wins by a perfectly pomaded hair. R.I.P., Buffy.

BUFFY ANNE SUMMERS

1981 – 2002

BELOVED SISTER

DEVOTED FRIEND

SHE SAVED THE WORLD

A LOT

Winner: Mad Men

Stephen Karam is the author of the plays Sons of the Prophet and Speech & Debate.

* This post has been corrected to note that the Kodak speech came during season one, not two. Also, two Anna Draper-related errors were fixed. Our apologies to her surviving relatives.