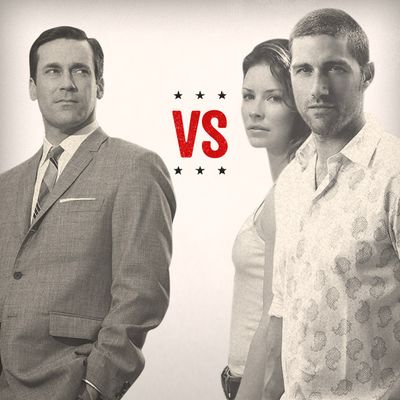

For the next three weeks, Vulture is holding the ultimate Drama Derby to determine the greatest TV drama of the past 25 years. Each day a different notable writer will be charged with determining the winner of a round of the bracket, until New York Magazine TV critic Matt Zoller Seitz judges the finals on March 23. Today’s first-round battle: TV host and Vulture recapper Dave Holmes judges Mad Men versus Lost. You can place your own vote on Facebook or tweet your opinion with the #dramaderby hashtag.

You’ve surrendered whole weekends to the DVDs. You’ve literally talked about them around the water cooler. Lost and Mad Men are two perfect examples of our current new Golden Age of Television — shows that have inspired not only loyal followings, but also countless books, podcasts, college courses, and one tasteful collection of reasonably priced workwear at Banana Republic. But only one show can win here. So let’s discuss them, starting with the time-traveling polar bear in the room: Lost.

In this Chuck Lorre–The Bachelor–NCIS: Special Victims Unit network-TV environment, it’s almost impossible to believe someone even got a meeting at ABC about a show with a smoke monster. I can’t think of a more ambitious television show than Lost, and its pilot — the most expensive in television history at the time – raised questions that kept us returning to the program, even when it was clear we weren’t going to get the answers. Its success meant even your dumbest friends were talking about flash-sidewayses, The Numbers, and faith versus reason. Lost made 2004 a deeply weird time.

We’d never seen anything quite like Lost, and though many have tried to be The Weird Show since, nothing has made the supernatural more palatable. It was, quite simply, the most batshit, mind-bendingly crazy smash-hit network show ever. Seriously, do this: Call your parents and explain the show to them. I’ll wait. See? They were out before you even got to the hatch.

But the creators of Lost — J.J. Abrams, Damon Lindelof, and first-to-make-it-off-the-island Jeffrey Lieber — knew that, as crazy and complicated as the show would get, TV audiences were intelligent enough to follow along. This was a show that had at least three separate realities going all at once, and yet was frequently TV’s top-rated drama. It gave a person faith — not just in showrunners Lindelof and Carlton Cuse’s ability to juggle competing narratives, but in our fellow audience members’ ability to keep track of what was going on. And the show’s left-field twists weren’t employed as some kind of Lady Gaga–style, weirdness-for-weirdness’s-sake crutch; such choices actually moved the story forward. Season one laid so much on the table with such confident storytelling, it established trust between the viewer and the creators, so much so that when the producers introduced time travel — four seasons in! — you would just sit back and say: “Oh, well, of course.”

Moving from hatches and smoke monsters to scotches and chain-smokers: Who among us had high hopes for a basic-cable workplace drama about misogynist executives in an early-sixties advertising agency? There’s no time travel on Mad Men, but, in some ways, it’s just as weird as Lost, anchored by creator Matthew Weiner’s subtly progressing narratives, Albee-esque dialogue, and morally elastic protagonists. Yet, like the Lost boys, Weiner has always trusted his audience to stick with him. And, on a macro level, that’s perhaps the most notable shared trait between these two shows: They both make us feel so damn smart right there on our couches.

But let’s break down the shows even further, beginning with their cast of characters. We must start with our leading men. Jack Shephard and Don Draper are both reluctant leaders with mysterious pasts and difficult fathers, each trying to keep his new family together. History will vindicate Matthew Fox, despite what Seth Rogen’s Knocked Up character might claim: His Jack, literally picked out of thin air for a leadership role he never wanted, is fully believable, human, and frequently shirtless. Isn’t this what we ask for in our protagonists? Much is made of Jack’s role as a man of science (in opposition to Locke, the man of faith) but ultimately he is, out of necessity, a man of action.

Don Draper, on the other hand, is a man of words, constantly massaging and manipulating. And Jon Hamm, on the other hand, is Jon Hamm. Does anything more need to be said at this point? He basically jumped out of the screen with a kind of fully adult masculinity and intelligence that we haven’t seen since Robert Mitchum, and the goofball extracurricular work he’s put in since season one (SNL, 30 Rock, Bridesmaids, comedy podcasts galore) has underscored the chops he’s brought to inhabiting Don Draper. This is not just a steely, slick hunk they found who fit the wool suits. His depth is never so clear as when Draper visits California and shucks off his besuited control, loosening up as Dick Whitman; it reveals the feat of this actor playing an actor. By contrast, Matthew Fox’s Jack comes off a bit dour, maybe owing to the relative scarcity of good Scotch on the Island.

Lost and Mad Men are both, in their ways, workplace dramas, and as such, they have massive, strong supporting casts. But Lost’s call sheet kept growing and growing, as Others and Tailies and Jeff Fahey popped up; such characters, spread across time and multiple universes, often didn’t have much more to do but glower and represent. But while Sterling Cooper’s client list has grown, the show has kept the focus on the (workplace) family, allowing seemingly peripheral players like Sal Romano, Harry Crane, and Lane Pryce to thrive. It could just be a matter of setting: Mad Men’s pre-sexual-revolution New York simply gives its characters an enclosed, heated space in which to interact with each other in a recognizably human way. On Lost, characters were often separated by time and space, and sometimes whisked away altogether for weeks on end. (“Waaaaaaalt! Waaaaaaalt?”)

Both shows also excel at slowly unraveling those characters’ backstories. From the start, Lost moved confidently back and forth in time and trusted us to keep up. “Walkabout,” from season one, is a perfect example: John Locke — whose on-the-nose name is the most notable example of the show’s occasional heavy-handedness — is the only one of our castaways who seems to be liberated by being stranded on an island, and the flashbacks into his life before the crash show us why. An alpha on the island, Locke was a victim in his previous life, saving up for years to go on a walkabout he’s denied at the last minute. In the episode’s closing moments, we learn that the pre-Island Locke had been confined to a wheelchair. It was one of those moments where you actually say the word AH! out loud, your wonder only slightly diminished by the fact that it would take forever to explain how he got in that chair in the first place.

Mad Men has its own mysteries: We still don’t know whether Don and Joan ever did it, or just how much Betty was in the dark about Don’s various sextracurricular activities, or get a good look at the tryst between Roger and a young Mrs. Blankenship. And we probably never will. With the exception of the occasional Dick Whitman flashback or conversational aside, Mad Men keeps moving forward. Its characters can’t suddenly drop into the desert or wind up in a magical pyramid; they’re rooted firmly in recent history. There’s only one consistent reality here, and it’s ours. Mad Men moves forward, not sideways, into the time of Medgar Evers and Lee Harvey Oswald (neither of whom, I presume, will ever be discovered pushing buttons in a hatch). We may not know where the characters are going, but at least we can relate, in some small way, to the times in which they live.

Ultimately, these are both shows about families that find each other. Mad Men’s season four masterpiece “The Suitcase” is essentially a two-person show with Elisabeth Moss’s Peggy blowing off her parents and boyfriend to brainstorm, drink, and spar with Don, and it works because despite his brusqueness, he sees her potential as a copywriter. In his almost fatherly way — but who can tell with Don? — he helps her realize her true self. Lost kept coming back to the pain of isolation as a theme; no character could survive alone. Sayid couldn’t make it on his own in season one; Charlie couldn’t find satisfaction until he created a family with Claire and Aaron; and Desmond, stranded in the hatch, almost killed himself, until he read the words that sum up the show for me: “ … all we really need to survive is one person who truly loves us.” And it was the connections these souls had to each other that allowed them to pass into the next life, according to the finale. (I think.)

Against Mad Men, Lost suffers two major handicaps. First, a major-network hit demands a grueling pace, output, and constant escalation that is less of a factor at a basic-cable boutique. The upending and hyper-tantalizing cliffhanger at the end of Lost’s season-one finale — in which Walt gets kidnapped and Jack and Locke finally blow off the lid of the hatch, then peer into a teasingly bottomless tunnel — is some of the best, most frustratingly compelling television I have ever seen, throwing out question after question and bulldozing the walls around the world we’d been shown. But fans’ voices go up an octave when they talk about season three, which began with Kate and Sawyer’s never-ending prison flirtation; the show seemed suddenly aware that it would be on for a few more seasons than it originally thought it would be, and the pacing of those questions’ answers slowed down even as the story got a little bit too busy for its own good, adding more mysteries to the mythology. If the creators had a Matthew Weiner kind of deal, under which they could have put out shorter seasons when they were good and ready, who knows how tight Lost could have been?

And then there is the ever-divisive finale, which left a vocal fan faction apoplectic, claiming that all the questions left unanswered earned the show retroactive demerits: After all, Evel Knievel didn’t get points for leaping over the Snake River just because he announced he could do it. And yet there was also the satisfied camp, who believed that the Oceanic Class of ‘04 reunion in Heaven was the perfect closure for the castaways’ tortured journeys. Either way, as judge I will order the finale stricken from the record. (Order! I demand order in my courtroom!) The finale factor makes for an unfair comparison, as Mad Men has not yet reached its endpoint: Finales of beloved dramas are dangerously combustible (Lindelof and Cuse were working with a higher-grade dynamite than that which blew up Arzt), and Weiner has not proven that he can satisfactorily bring Don Draper’s story to a close. He has recently said that he has a last scene in mind: Who’s to say it’s not Don and Peggy finding out that Sterling Cooper was the afterlife? (It would certainly explain all the ramification-free smoking.)

And yet, even with Lost’s conclusion removed from consideration, Mad Men wins. At its best, Lost was a blockbuster summer movie every week, the best kind of blockbuster: a frantic, cryptic, addictive, wonderfully imaginative adventure. It triggered hours of brow-furrowing online debates about the meaning of all those totems, asides, comic books, records and millions of other clues real and imagined. But ultimately, the “meaning” was all about the plot. Mad Men is about what we mean. It is set in nearly as exotic a land as the Lost jungle, but every un-PC, pointed, shrill remark or act of repressed discontent, every manipulative ad campaign, every wish fulfilled and not, every grope and every gasp, shines a revealing light onto our contemporary, allegedly more evolved world.

Lost held a regular debate between faith and reason, but these opposing viewpoints served mainly as antagonistic character traits; they didn’t seep into our own realities. (Unless, of course, you are stranded on a magical island with magically repaired legs, in which case: apologies. Also: Get a load of you!) Mad Men also holds an ongoing debate between faith and reason: Dick Whitman had faith that if he could only collect all the trappings of success — corporate office, trophy wife — then he would be a new, happier, more worthwhile person. And as Don Draper, the strived-for personification of those wants, Whitman wrestles to subdue the suspicions that there is something important beyond simply creating an illusion. Mad Men plays to an upscale audience, and disconcertingly picks at their very existence. It’s exhilarating to visit a world governed by magic numbers; but it’s more satisfying to visit a world in which numbers don’t solve anything.

Winner: Mad Men

Reader Winner as determined on Vulture’s Facebook page: Battlestar Galactica

Dave Holmes hosts shows on TV (FX, H2, many more) and the internet. He blogs at daveholmes.tumblr.com, tweets at @daveholmes, and performs at LA’s Upright Citizens Brigade and IO West theaters.