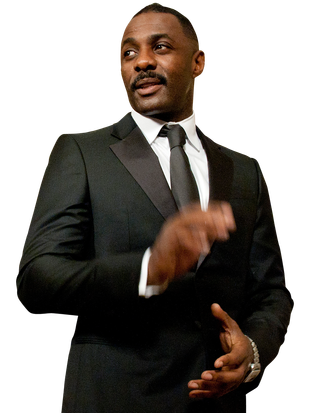

When reading this interview, please picture the man who played The Wire’s Stringer Bell sitting in front of you on a bench in the back garden of the Crosby Street Hotel. He is six-foot-three and dressed smartly and simply in a tweed cap, black Nike sneakers, gray jeans, and a black long-sleeved shirt — that fits perfectly. Have you seen him on Luther, the British TV series in which he plays a brilliant but possibly sociopathic London police detective prone to violence and fervent ardor, often in the same instance? Good. Think of that non-posh British accent caressing the words below. Throw in a brilliant smile or a hearty chuckle at will. This was what it was like, dear readers, to spend an hour and a half with Idris Elba on his whirlwind press day for Ridley Scott’s Prometheus, which also happened to be his “day off” from shooting No Good Deed, before moving to South Africa to play Nelson Mandela in The Long Walk Home. We already wrote about our Elba encounter here in detail. Below are the raw goods. Set your image of him. Is it beautiful? Now off we go.

I heard you were working until four this morning in Atlanta before taking a plane to New York. You’re shooting No Good Deed?

Yeah. We’re doing night shoots and I flew straight here. I just got some sleep, but it’s still a little foggy.

I don’t know much about the film.

It’s a thriller with Taraji P. Henson, an old-school thriller. I play a character that … well, without giving too much away, he basically breaks out of jail and then terrorizes some people. [Smiles.] I’m excited. Sam Miller, who directed the second installment of Luther, he’s directing it. It feels good. It’s a good sort of slow-boil, old-school drama.

You’re executive producing it, too?

Yeah. I want to produce and direct. This is one of the first exercises of me sort of bringing a team together to make something that I think will be good.

Give me a sense of your life right now.

I’m three people at the moment. So, the person that you see in front of you, the character that I’m playing in No Good Deed, and I’m prepping for Mandela as well at the same time. I’m sort of split. I’ve been training quite a bit as well, so trying to fit that in, because Mandela used to box. So, I’ve been boxing. There’s not much sleep right now. Not many friends around me. There’s not really any time. I’m sort of doing, like, 28-hour days.

When I think of Nelson Mandela, his being a fit guy is not the first thing that comes to mind.

When he was younger he was incredibly fit. He used to run four miles every day at four in the morning. His lifestyle back then mirrors my lifestyle now. Just very busy.

You spend half your time in Atlanta, right? Which is where you’re shooting No Good Deed.

No. I don’t. I just own a home there and my daughter, Isan, lives with family there. I’m in and out there, and she’s in and out to see me.

She’s 10 now and you’re working all the time. So how do you manage to see her?

A lot of organization. Sort of time management, basically. It doesn’t feel as organic as normal parenting. It’s like, “Oh, Dad, can I talk to you?” Yeah. You have to sort of allocate time and do things in a way that allows me and her to hang out. But we manage it. This shoot was definitely designed so that I could be at home for a while.

You’re going to have to go to South Africa a few days from now?

Next week, yeah. For seventeen weeks.

Are you at all prepared for that much time there?

We knew when we sort of sewed these jobs together that this was going to be a bit of a really challenging time. It really is. But, mentally, I’m prepared for it.

Have you packed?

No. I haven’t packed. I’m still suitcases. I mean, I went straight from Prometheus to Pacific Rim in Toronto for five months. I literally left there and came to work in Atlanta.

Are you sick of all your clothes at this point?

Yeah. I’ve worn this outfit a million times.

You just try to go with the black-gray combo.

I do. The only thing I change mainly is my sneakers. I love sneakers. But everything’s sort of black or jeans. Jeans, always.

Well, those are pretty nice sneakers. Are you, like, Nike obsessed?

Not obsessed with particularly Nike, but sneakers in general. I love them.

Do you have a separate suitcase for the sneakers?

I tend not to bring my really fly sneakers with me, otherwise they get ruined. I just bring an assortment.

Where are you living? Is London home now?

No. No fixed abode, to be honest.

You don’t actually have an apartment?

No. [Laughs.]

Where do you keep all your shit?

In storage. I don’t have a place that I call home at the moment because there’s no point. I mean, I’m a traveling circus for a while. It’s weird. Like, if I wanted to go home, there’s nowhere to go. I just go to a hotel. But I’ve kind of gotten used to it.

Your Mandela schedule means you’re missing the Prometheus premiere and the London Olympics.

I’m not upset. It’s just one of those things, the biggest film in the world and biggest event of the world and I can’t be at either. I definitely wanted to be at the Olympics. It’s in my neighborhood where I grew up, in Hackney, and I’ve done some work with the Olympic team as an ambassador. So I certainly feel like I should be there.

Tell me about shooting Prometheus.

I play Captain Janek, who is the captain of the ship basically, central to most story lines but not heavy in all story lines. Good part. Very much a working man. Everyone else in the film has sort of a scientific background or whatever. But my guy’s an engineer. He’s a pilot, flew war planes and now flies spaceships.

He wears a hoodie sweatshirt while everyone else seems to be in more standard space uniforms.

That’s the idea. We want you to feel like you’re looking at longshoremen or sea men that travel for long periods of time.

It seems like a lot of what you had to do was maybe stand in front of a green screen and pretend like you were seeing space. What was it like to shoot all that stuff?

Well, the actual spaceship was built. Not in its entirety, but all its interiors are full formed, built to scale, real size, functional. Ridley [Scott] wants the actors to feel as real as it can be. The green-screen acting was only outside of the windows, when I did the spaceship taking off and landing, that type of stuff. To be honest, it didn’t affect me this much. In Thor, for example, when I was in that, there was a lot of green screen. You’re literally talking to an actor with nothing around you.

What made you want to do Prometheus?

I wanted to work with Ridley again. I loved working with him the first time [in American Gangster]. His return to this genre is a landmark in filmmaking. So to be a part of that certainly it feels like a big achievement for me. Ridley called me and said, “Look, this film isn’t about Captain Janek at all. But I want a really good actor to play this part.” So, he gave me the job and it was great.

This might be, like, your biggest movie.

Biggest movie that I’m in, not biggest part.

You did two sci-fi things back-to-back, Pacific Rim and this. How did the monsters compare?

Well, Guillermo del Toro’s film is much more an Earth/human story with the looming attack of another race. Very different. Guillermo del Toro is an amazing director to work with. I learned so much about precision from him — about looking at you now and then looking one layer behind you at the leaves and then looking at the wall behind you and then looking at shadows on the wall. My depth of field is now so unbelievably clear I feel like I want to direct now because of what Guillermo taught me.

Really? What were the various things that you learned from him?

His attention to detail is amazing. His attention to sort of how to manipulate the audience to keep driving them forward in the story. As an actor, you kind of say the words, but he wanted us to really connect to each emotion. Whether the last time you saw me on the screen was six minutes ago or not, there was a real sort of connection to each one any time you were seeing me. That’s not something you teach, but it’s something that I was aware that he was paying attention to. It was interesting.

What does your character do?

He’s yet another man of authority, but this time much higher up. He’s the head of the army and the army is the essential fighting force against these monsters. The world is crumbled and this alien lived underneath the surface of the Earth for a long time. Our only defense has been these massive robots that fight back — they’re basically tanks that are put together to look like men and can walk. I play the leader of that sort of movement. Then we lose our funding, basically, and the world decides to build walls around countries, which basically means the rich can get in and the poor can’t. So our characters go, “No. We’re going to fight this our way.” It could be a box-standard, fight-against-the-aliens sort of film, but not with Guillermo.

It sounds like it’s almost a commentary on class and immigration.

Well, it’s certainly a commentary on if the world were under attack who would survive and who wouldn’t. Interestingly enough, the poor would probably more survive than the rich.

Why is that?

Because they have less and are used to less; therefore, more resilient and more tough. If an alien attacks a big skyscraper, people in the skyscraper are going to die. The people on the floor may not.

Pac Rim takes place 20 to 30 years in the future. Where are you going to be 20, 30 years from now?

Twenty or 30 years from now I’m going to be on a beach in Jamaica.

Doing what?

Nothing. [Laughs.] No. I’ll probably still be a filmmaker, if I’m still alive. I’d love to be able to make films until the day I die.

So the goal is to make enough money that you can sit in Jamaica and not worry about invading aliens?

Not money. I’ve been acting for twenty years. What keeps me going is the fact that I want to do something I haven’t done before. I’m not a household name and I love that because it keeps me … it allows me to keep growing and breathing. No one goes, “Oh, it’s Idris Elba’s movie.” Or “It’s an Elba picture,” or “It’s typical Elba.” At this point, even though the films are getting bigger, I’m not getting more famous. That’s an interesting position it be in as an actor. You’re doing more, you’re recognized as a great actor, but you’re not a household name.

You’re kind of a household name in the households that I know.

Really?

I mean, all my friends love The Wire. You’ll never be able to do anything wrong after you did that role.

Right. Okay. But my thing is, like, they know Luther, they know Stringer. I mean, I don’t know whether they do or not. But I suspect that … I’ve got a publicist and I’ve had one for two years. She’s like, “Sometimes they don’t get it. They’re like, ‘Ee-dris Elba?’ ‘You know, the guy from The Wire.’”

So do you pronounce it Ee-dris or Id-ris?

Id-ris. I was saying Ee-dris because that’s how most people pronounce it in America. I guess my perspective of it is that I don’t see myself [as famous]. I see myself as an actor people know, popular perhaps. What’s his name again? — it’s that.

Where did your name come from?

West Africa.

What does it mean?

Idrissa is my name. Idrissa is sort of like a firstborn son.

Why’d you take off the A at the end?

It used to get me in trouble at school. It was very feminine sounding. I’d get teased and end up beating someone up.

This happened often?

As a kid, yeah. I was really conscious that my name was so different. Everyone was called Jason or Terry or James or Michael. Then there’d be Idris. My name would always get a snicker or two when I was a little kid.

I don’t know London, but from what I’ve read, the neighborhoods you grew up in were kind of rough.

I was born in Forest Gate and lived in Hackeny and in Canning Town. We moved to Canning Town when I was going into the first year of high school.

Because it was nicer than Hackney?

According to my parents it was nicer, but it was just as poor. It was mainly white and Indian, as opposed to Hackney, which is very mixed. Canning Town was like a slap in the face, like, “Wake up! This is the rest of the world.” I was very much a Hackney lad.

What does that mean?

Do you know who the National Front are? They’re an extreme right-wing party. Their beliefs are: Keep Britain White. Well, Canning Town was a hub for the National Front. So when I got there, I realized that there was that tension there. But I wasn’t going to be a part of that at all. I’m from Hackney, you’re telling me to — I used to get in fights with white kids all the time because they were stamping all over people. I was like, Fuck that.

But they weren’t picking fights with you?

They were picking fights with me. Walking down the street someone would call you a black cunt. “What? Who the fuck you talking to?” Then mum [says], “No, no, no, leave it, leave it. It’s all right. Leave it.” “No! What? It ain’t all right. Who you talking to?” Fight. I got quickly well-known in my neighborhood because I was a tall guy but I just wasn’t taking any shit.

So maybe this is why you now get all these authority figure roles.

Maybe. Well, yeah. I guess Luther and Stringer are sort of …

I think they’re both leaders. Stringer’s a leader.

Yeah. But he was second in command.

He wanted to be first in command.

I think Idris Elba, in reality, I don’t know if I’m a leader. I don’t follow many people. I lead myself, if you like. I’m one of those people that if I was to sit on a team and the team leader was no good, I’d quickly switch off. I would be like, “No. I’m going to do something else.” I wouldn’t become the leader, though.

When you got the Golden Globe for best actor in a miniseries, I remember you saying that Luther changed your life. How’s that?

Prior to Luther, I was doing sort of like drop-in film work: Obsessed, Takers, This Christmas — films that were sort of more in a space that was skewed urban, if you like, and smaller films. Good parts, but smaller. Luther gave me an opportunity to show that I love to act. I’m a character actor in my heart of hearts. So, Luther gave me not only a confidence, but a showcase to kind of go, Oh yeah, that’s right, I do make up these other characters and can act. Plus, it changed the kind of people that were calling. I got Pac Rim because Guillermo loved the show. Ridley saw me again in Luther and was like, “Oh my God, I promised Idris he and I would work together again.” Because he did. And then we did.

Luther really let you fly off the handle, whereas Stringer always seemed in control.

I think with Stringer, I brought an English sensibility to an American character, and with Luther, I bring American sensibilities to an English character. Stringer, on the page, he read like the consigliore, the man next to the man. But I sophisticated Stringer up with how subtle he was. Luther — he’s way bigger [in his reactions] than an English cop would ever be. He’s very American-esque in that way. I think part of the TV show’s popularity in England is that it’s sort of ridiculous to see an Englishman that big in a lot of these scenes. But it actually works because of how grandiose some of the crimes are.

Sometimes Luther seems mentally disturbed.

I think he had some sort of trauma. The thing about being traumatized, if you’re a size 12 and you traumatize your shoes, when you put your shoes back on, they’re probably bigger than the last time you wore them. I think that’s what happened with Luther. I think he just didn’t come back to his ground zero after some really traumatic things in his life.

A friend of mine said if anyone wanted proof you’re a great actor, they should watch Stringer’s death scene.

I can’t even remember.

You can’t remember the death scene?

I can. But it’s so long ago now. It’s been seven years.

You had a small role in American Gangster, but other than that you haven’t played a gangster since Stringer, right?

Yeah. I was getting offered that type of role again and again. I was like, “Ahhh, done it. Can’t top something like that.”

I guess maybe Luther brings you up in conversations for leading man parts more now.

Yeah. For sure. Yeah. You’re a lead in a show and you’re seen in that world.

Was getting lead roles before Luther hard because you’re not a household name, as you say, or is it also a function of race and discrimination?

Maybe a combination of all of the above. Not to mention that America has hamburgers, so why do they need any more?

You mean, why do they need a British guy when an American can do it?

Why do they need more actors? Why do they need more leading men? Every leading man — black, white, or other — is fighting for a handful of spots now. In fact, the tradition of the leading man is dying. That sort of handsome leading-man actor with a lifelong career because everyone adores him, audiences have moved on from that. They like more fresh faces. I’m not saying that’s over completely, but it’s definitely not as abundant as it was before. I feel like I come from a school of actors like — what’s my man’s name? — Bradley Cooper. It’s a school that’s come from good ensemble acting and television backgrounds. It’s just a longer process. They don’t pop up in one movie and suddenly they’re a superstar. Bradley’s part of a franchise, The Hangover, which is bigger than him as a leading man.

Well, how do you feel about opportunities for black actors right now?

Next question.

What?

I’m so bored of answering that.

Please, do tell me why.

Because it’s asked every time. I mean, I said it in an interview once or twice that opportunities are not the same. It becomes a place where every journalist wants to go to. It’s just boring now.

I love that you’re telling me that.

It’s true. There’s no such thing as a black actor or a white actor. We’re just actors. Are there differences between black actor’s opportunities? Yes, there are. It’s been said.

I guess it came up again because Samuel L. Jackson wrote in a letter to the Oscars in 2011, something like, Why isn’t there a single black presenter at the Oscars? There were articles about it recently.

I don’t know. Let the work do the talking. For a younger actor that is black and reading this article, I’d rather him hear about the success than about how tough it was. I just feel like we’ve had those moments, hugely. Anyway, everyone’s going to be brown one way or another. It’s true. It’s just a fact. It’s the way the human race is going. Everyone’s going to be brown.

You mean mixed race? I’m mixed race.

Yeah. Right. The term brown means there’s so many different cultures mixing now. Who’s who? So I tend not to answer that question anymore.

What do you think does attribute to your success? Was it just keeping your head down and hard work?

Luther, Stringer Bell, being awarded jobs where the character wasn’t neither black nor white — those are success stories to me. Stringer Bell is a drug dealer.

But there’s no way a white actor could have played that role.

Yeah. But I have more white fans of Stringer than I have black fans. You know what I mean? It has nothing to do with the fact that he’s black at all. It wasn’t that Stringer was black or white that made him attractive or appealing. It was his situation and the way he dealt with that. If anything, the whole Wire clan was more reminiscent of a classic Italian gangster family than it was what we see in the stereotypical drug family. I lost my train of thought.

I think you were talking about just getting roles and how that’s success.

Yeah. I get these roles because I can act and that’s it. [Pauses, laughs.] Hopefully that’s it. I think the less I talk about being black, so to speak, the better.

You started off D.J.-ing weddings as a teenager with your uncle, right?

Yeah, big African weddings, lots of Calypso and African music, the electric slide. I get asked all the time, “Mr. Elba, can you come D.J at my wedding?” [Laughs.] D.J.-ing was the way I really made my money as a young actor, even when I got to go to the States. I brought my records because I couldn’t afford to just sit around waiting for auditions all day.

Now that you’re so busy with movies, has D.J.-ing been put on hold?

Just taking a different form. I live virally more than I actually do in clubs now. I just D.J. on mixtapes and send the mixes out. I’m currently working on three mixes [house, dub-step, and hip-hop] for Prometheus — and wait for it — I did a play on the words. You’re going to look at the title and you’ll say it says Prometheus but it doesn’t. It says “Pre-mixed for Us.” Isn’t that clever?

Ha. Yes.

Anyway, I’m doing a series of mixtapes for this film. I love it. I mean, in my bag upstairs you’ll get the clothes that I’ve been wearing for months. Then you’ll get my little D.J. unit that I mix in my bedrooms.

How are you mixing? What do you use?

Right now I’m using Traktor, which is a software made by Native Instruments. It’s just a D.J. software where all MP3s live on a hard drive, drag them into files.

Are these licensed or unlicensed Prometheus mixtapes?

Funny enough, I had to ask permission because … I mean, I think because a D.J. is kind of taste-maker and being in one of the biggest films of the year is a great synergy for both them and me. I don’t D.J. under Idris Elba. I D.J. under 7 Wallace.

I thought you had a different D.J. name, or at least Wikipedia thinks you do.

It’s just Idris or Big Dris. Someone said my D.J. name was Dris the Londoner, which isn’t true.

What does 7 Wallace mean?

It’s an address that I lived at during the first season of Luther. It was a party house.

You had a party house?

Yeah. Even while I was working.

Did you have roommates?

No. But my house was big enough that all my mates moved in, practically. When you watch season one of Luther, understand most of those scenes were with a hangover [laughs], which is what made it more grumpy and interesting to watch, I think. But 7 Wallace, everyone was like, “We’re going to 7 Wallace tonight, 7 Wallace tonight.” It just stuck as a D.J. name.

Was the party house planned?

Yes and no. As soon as I saw the place I was like, “Okay, this is huge. I could fill it and have fun in it,” and I certainly did.

Were you throwing all-night ragers? I think this is really interesting.

Well, it was basically I had all my mates — here we are in this big old house. “Let’s have a drink.” That’s how it became. Then every other weekend, basically the turntables were out. We had a Luther wrap party at 7 Wallace, which was bananas. Interesting enough, when I talk about 7 Wallace, people always think it’s about Stringer. Like, “Oh, where’s Wallace, String? Where’s Wallace?” Or they go, “Is that an ode to Biggie Smalls, Christopher Wallace?” No. But in 7 Wallace, we had a Christopher Wallace suite, which was the living room, which was for Christopher Wallace–type activities.

What are those?

See, you’re going to have to use your imagination. [Grins.] If you know who he is, then you’ll know.

Are you going to continue this party house in South Africa? Do you have a plan on where you’re going to live?

I’m going to be all over. I’m going to be in Cape Town a lot and Johannesburg a lot. I can’t really talk about the process of that film yet. It’s just one of my biggest opportunities, you know.

You can’t speak about how it’s been preparing for that?

Yeah. I can’t think about where my head is at for it, what I’m doing to prepare. I just get this sinking feeling as soon as I open my mouth.

That you’ll fail?

No. It’s kind of like I just want to get off to the races. I don’t want to talk about it. I just want to do it.

Are you nervous?

I wouldn’t say I was nervous, but I recognize the responsibility attached to the role. If I had it any other way, I wish I had designed it differently in that I wasn’t working directly up to it.

But you have been preparing boxing. I heard you’re obsessed.

I am. Yeah. I’m actually training for a charity fight in the New Year. Mandela has gotten me so obsessed with it I actually want to fight. I’m two minutes away from commissioning a documentary about my journey as a fighter. I’m 39 years old and now would not be the ideal time to start boxing. [Laughs.] But I just find it so fascinating, the conditioning. And I’m dog tired right now, but I’m fighting through that. Usually I give up, I just want to go to bed, and will. I’ll say no to interviews. But at the moment I’m using this fact that I’m working as hard as I’ve ever worked in a gym. It parallels the hard work that I’m putting into my film work right now. It’s sort of like the discipline it takes to play these different characters is similar to the discipline it takes to get up and do two hours of really hard labor in a gym.

So, I want to make a documentary about my journey. It’s going to be a year. I’m working with two trainers, a boxing training and a fitness trainer. I’m going to bring them to me wherever I’m filming, from Mandela in South Africa to Thor 2 and Luther [season] three in London. I’m really excited about that fight. My parents are from Sierra Leone and I’m trying to build this children’s charity because kids there tend to die very young. I want to use the boxing as a way to raise money for it. Plus, it’s just a huge challenge for myself as a man hitting 40.

What is it about boxing do you think that is so appealing to you? Is it like Luther, a regulated outlet to unleash anger?

I’m not a violent man. I can be, but I have to get over the mental barrier of, like, “I don’t really want to hit this guy.” My draw into it is about the physical challenges to a man my age. Everyone thinks they can box: Come on, left, right — whatever. But the measure of sort of fitness is what’s really incredibly appealing to me. When they say a fighter is fighting fit — I mean, if an alien craft was to come down and go, “We want the fittest people in the world to come,” [it would be] a bunch of soldiers and a bunch of boxers and fighters. I’m serious. Their endurance and level of fitness is out there. I want to take my body there. I really do.

Is there any worry that as somebody who makes his living off his face, you should not get totally pummeled in this match?

Well, if I made my living off my face alone I don’t think I’d be here talking to you right now. I don’t think I’ve got much to lose.

You don’t want to go down the Mickey Rourke route.

Mickey changed his face. I think me and my one or two charity fights, I don’t think are going to change me drastically. But even if it did, oh well. There are characters out there that have crooked noses. I think I’ll get those characters.

Can you tell me anything about what’s going to happen with Luther in the third season?

Well, we’re going back to a four-episode format, high-octane Luther stuff. We’re going to close out a couple of story lines. We’re really preparing for the big-screen Luther. It’s a goal. A very strong goal. It’s not in stone yet, but it’s something we definitely want to aim towards.

When you say that you want to just keep playing things you haven’t played before, what are the roles that you need to tick off on your bucket list?

I haven’t done any romantic comedies. I haven’t done many comedies. I’d like to do some films skewed towards children. I love kids and kids like me, so I’d like to do something a bit silly and in that world.

I wonder if Stringer or Luther sort of makes people not think of you in those?

Yeah. I’m not getting offered roles by Disney at all. [Laughs.] But I’d love to try something like that. I admire Dwayne Johnson, the Rock, and those type of films are such fun. My daughter loves those type of films.

What do you admire about Dwayne Johnson?

Oh, just his fearlessness in taking roles like that. He’s known for being a hard man and he has a fearless approach to playing roles that are the opposite of that. That’s great to me. That shows versatility. I like him, I like that.

I don’t know if you know about this, but there’s a bit of an online movement to get you on The Good Wife. Do you know that show?

I know what it is. I haven’t seen it.

There’s this badass character, Kalinda, played by the British actress Archie Panjabi. Kalinda’s husband, who is a dangerous man we’ve never met, just returned in the season finale. We hear the knock on the door, but we don’t know who will play him. And every message board was like, “Idris Elba.” You’re at the top of everyone’s wish list.

Really? No way. Good Wife’s a good show, right?

Really good. Think about it! Though I think you’ll be shooting Mandela when they’d need you. Is TV still something that interests you or are you sort of straight on movies now?

No. I did The Big C just before I did Prometheus. I love TV. It’s my world. As long as I don’t have to play the same characters over and over again.

I wonder if The Good Wife would skew too closely to what you’re sick of playing: a sexy, dangerous man.

I’m playing a sexy, dangerous man in this film right now, though I don’t find him sexy at all. I just find him depraved and horrible. But our goal is the audience has to like him even though they know he’s done heinous shit. That’s quite an interesting thing to play, actually.

When you go back for the third season of Luther, are you going to resurrect the 7 Wallace party house?

I’m probably going to get a residency D.J.-ing at a club somewhere as opposed to my house. I won’t be drinking at all. I’ll be training all the way to the charity fight, which will be in March or April [of next year].

So September is when you come back from South Africa. Then right after that is Thor, then Luther season three, then the fight.

Yeah. In London. I’d rather be on a beach in Jamaica.

Not yet. Not until twenty years from now.

Can I just have a week off? That’s my goal right now.