How Edward Albee Was Still Redefining Himself

Edward Albee died today in his Long Island home at age 88. We are republishing this piece, which originally ran on September 30, 2012.

African sculptures lined up in ranks as if at a tribunal glare implacably at visitors to Edward Albee’s Tribeca loft. Albee himself, though noticeably frailer since undergoing open-heart surgery in June, nevertheless holds his own among them. He sits quite erect in a black leather chair, hawkeyed and beaky, all but growing into his collection. For someone whose 30 or so plays — including such masterworks as The Zoo Story, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, A Delicate Balance, and Three Tall Women — amount to an encyclopedia of human weakness, he remains at 84 reassuringly tough, both with himself and with others. His cane, that ancient sign of human decline, could still, the way he wields it, be a weapon.

But his toughness does seem to have changed in recent years. Both halves of his enfant terrible reputation have finally worn off. He no longer wastes much time on cut-glass insults meant to open veins or jeremiads against stupid critics and obtuse colleagues. These were behaviors that once led people to assume that the shocking, merciless characters of his breakthrough plays — like George and Martha, the apocalyptically bickering spouses of Virginia Woolf — were disguised self-portraits. Those characters remain shocking today; Albee less obviously so. Perhaps because he stopped drinking in the mid-eighties, and has never, he says, fallen off the wagon, or perhaps because of his grief over the death, in 2005, of his partner of nearly 35 years, the sculptor Jonathan Thomas, what once seemed galactically cold in him has been rubbed down and polished so much that it almost passes for warmth.

Almost. During a recent conversation, occasioned by the latest revival of Virginia Woolf — it opens on October 13, exactly 50 years since its Broadway debut — he twinkles but also jousts. There’s nothing vague or grandparental about him. Despite some hearing loss and the occasional “trouble concentrating” in conversation (though not, he says, in writing), he is the opposite of fading. He’s intensifying, saturating. Even his witticisms have achieved a deeper economy, beyond which you’d think communication might cease entirely.

And, in a way, it does. When I try to get him to discuss the fluctuating reputation of his plays, he leads me merrily around many barns.

“You’ve had several phases of more and less acclaim in your career,” I start.

“Yes, and not always justified in either case. Sometimes the critics let me off too easy. And some of my least popular plays are by far my most accomplished.”

“Was The Lady From Dubuque, which we saw rescued from anonymity earlier this year by the Signature Theatre Company, one of those?”

“It wasn’t rescued from anonymity, except in some people’s opinion.”

“Revived then, brought back to life.”

“But it was never dead. Any more than it is now.”

“Well, it could finally be appreciated by people who didn’t know the play before.”

“Then how come they had an opinion of it?” He relents a bit. “I do think that my plays, for some reason, have been more completely understood in second and third productions, when they are seen in a different time period, by different people, who have been trained to have different responses.”

“Trained in part by you.”

“Yes, I know.”

“So which are the plays you would most like to put back before the public?”

“The ones that have been before the public least.”

“And what about highly exposed plays like Virginia Woolf?” — the last major New York revival, starring Kathleen Turner and Bill Irwin, was just seven years ago. “How often do you think it’s good to have them produced on Broadway?”

“Whenever there’s a good production.”

Albee makes it sound as if that were left to chance. In fact, ever since The Zoo Story in 1958, he has been known for controlling whatever is possible for a playwright to control — and then some. The choice of directors, of course. The casting, sure. But also what the directors and cast actually do. He famously encourages them to experiment as much as they like as long as the result, down to the last scripted pause, exactly resembles his intentions.

During our conversation, he hands down several tabletsful of similarly exacting commandments, about playwriting and life. Never work on anything you’re not enjoying; “otherwise it’s just typing.” Never criticize what you’re writing while you’re writing it. Live in the reality of what’s happening, not in your interpretation of it. Every time you write a play, write the first play anybody’s ever written. Don’t strategize your feelings; just feel. Don’t write to solve your problems; you won’t.

The aim seems to be to plant his flag in an eternal present in which there is no expectation and no second-guessing. Still, he has often violated his proscription against revising old plays. In 2004, the one-act Zoo Story got sutured to a new one-act called Homelife to form an entity now known officially (and tellingly) as Edward Albee’s At Home at the Zoo. And most major productions of Virginia Woolf — his first full-length work and still his most famous—have endured his fiddling. For the 2005 version, he omitted several pages at the end of Act Two that he thought were overwritten. The current revival, starring Tracy Letts and Amy Morton, may well see the benefit of even further compression. “I don’t want to bore me or anyone else,” he says. Which is why the revisions, he insists, “are always cutting.”

“Always cutting” might well be his watch cry, if not yet his epitaph. There was some doubt about that earlier this year as his heart wound down. “I knew my body was getting weaker,” he says, “and I knew I was going to have to have something done. And they finally said to me, ‘Edward, you need open-heart surgery.’ When they rip your chest open and do all sorts of silly stuff to it. And my reaction to that was, ‘What will happen if I don’t?’ ‘You’ll probably die in a year.’ ‘Oh. Then I guess there’s no choice’ ” — and therefore, he assures me, no reason for him to have been afraid as he lay in bed this summer awaiting surgery. “Either the operation will succeed and I’ll have a few more years,” he recalls thinking, “or it won’t and I won’t know it.” In such a situation, fear must give way to objectivity, he concludes, because “objectivity insists on it.”

If he sounds like his dialogue, that’s his privilege. As a master of dramatic sleight-of-word, and arguably the most influential playwright of the last 50 years, he is partly responsible (with a hat-tip to Wilde and a low bow to Beckett) for creating a world in which it’s no longer surprising when conversation becomes a con. Virginia Woolf, which begins as naturalistically as an episode of The Honeymooners, soon jumps the tracks into a kind of sadistic surrealism in which a college-town couple, George and Martha, torment their guests and each other over a long evening of “fun and games.”

The wild invention of Albee’s language has lost none of its freshness, even as George and Martha have become American archetypes. (Given their names, it’s clear that’s what Albee intended.) In a PBS interview aired in connection with the recent Steppenwolf Theatre Company production on which the current Broadway incarnation is based, Letts, the author of plays including August: Osage County and Killer Joe, said that Albee’s style has become part of our theatrical, and by implication our national, genetic code. Albee, he added, has a way of making mundane moments pop, of “making them interesting, and especially humorous for an audience. He has a great wry sense of humor. Sometimes even silly, but almost always very smart.”

When I read this to Albee, he responds drily, “That was almost really smart.” And then another game begins.

“In playing George,” I ask, “is Letts’s being a playwright helpful?”

“I hope it’s helpful to him. Hasn’t always been. I like some of his plays more than others.”

“Which ones?”

“The better ones. The ones that interest me more.”

“Is that all we can ever mean by a ‘better’ play? One that interests us more?”

“Of course.”

“There’s no objective way to distinguish between what one enjoys and what is good?”

“No.”

“When you teach, you must be handed many bad plays. Perhaps almost exclusively. Are you sure that they’re bad?”

He makes an abstract sound that means yes and brooks no contradiction.

If his rules are circular, he nevertheless follows them. His most coruscating plays, including Virginia Woolf, are also his most entertaining. This seems to be a law of nature, or his nature at least. Enjoyment may be priced at a premium for a man who once had so little of it. (His parents let him know in a thousand ways that they’d made a mistake in adopting him.) At any rate, wherever pleasure might be found, he is unafraid to leap — even with a cane.

“For five years after Jonathan died,” he says, “I didn’t want to do much of anything. I certainly didn’t think I’d be capable of ever caring much for anybody else or feeling amazing responses to things. But two and a half years ago now, I suddenly, one day, realized that I had fallen hopelessly in love. And really seriously, not just infatuation. Somebody not only beautiful and sexy but enormously talented, genuine, generous. I didn’t think I was going to do that anymore. It was joyous. ‘My God,’ I thought, ‘you’re capable of this still?’

“And at the same time, I realized a couple of problems. I mean, I am 84 now. He’s 24.” He corrects himself. “In a couple of weeks, he will be 24. I knew it was absolutely foolish. He’s too young. He’s too this, he’s too that, he’s all sorts of stuff” — including, apparently, “not that way.” “It wasn’t going to work in that sense. It wasn’t going to be a great, wonderful sexual relationship. But, wow, wasn’t that interesting when I thought it was! Isn’t kidding yourself fun?”

A look of wonder passes over his face. “And so I am getting myself — not out of it … but out of concerning myself with it.”

You could argue that most of Albee’s plays — certainly Virginia Woolf — are variations on the theme of people being stuck in something (often a family) they can neither get out of nor stop concerning themselves with. Hence all the drinking and screaming. But paradoxically, as time grows shorter, Albee seems to favor more wait-and-see solutions. He applies a terrible, willful patience to the working out of his plots, whether real or fictional. A play called Laying an Egg, about a middle-aged woman’s attempts to conceive a child, was scheduled for a run at the Signature earlier this year but withdrawn as unready. It is now, he says, nine-tenths finished; he would like to see it produced, “and possibly have it partially understood,” in 2013 or 2014. Soon, he thinks he may be ready for a play arising from the death of his partner, or from his late experiment in love, or from one of the other ideas that keep being born in his head. And though he’d “be unhappy if they didn’t get written,” he refuses to worry about things that cannot be done. If some ideas die with him, he says, “no one’s going to know anyway.”

Of course, that’s not so; perhaps, I suggest, if he is so fecund with ideas, he should just give some of the excess to other playwrights, who have so few.

“Yes, except that I am not me.”

“ ‘I am not me’?”

“I didn’t mean that.”

“You meant, ‘They are not you.’ But ‘I am not me’ sounded so much better.”

“Well, I’ll say it next time.”

And then, as I laugh, something extraordinary happens. He chooses to stand by his mistake.

“Maybe I’m not me,” he considers. “Maybe I’m the result of what I need to appear as. I don’t know.” He twinkles one last time. “None of us ever knows that.”

*This article originally appeared in the October 8, 2012 issue of New York Magazine.

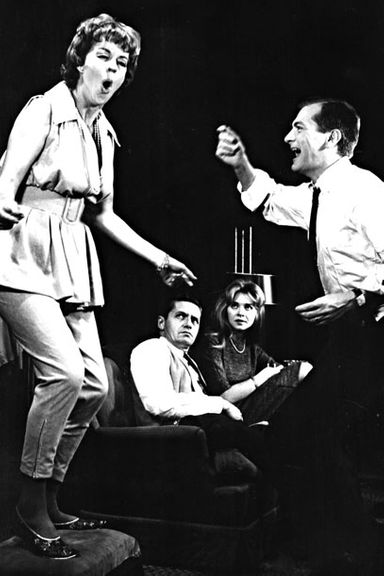

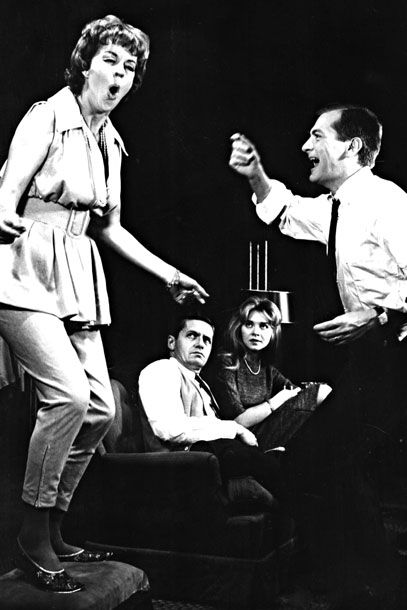

Uta Hagen as Martha and Arthur Hill as George in the original stage production in New York (1962).

Photo: Everett Collection / Rex USA...

Uta Hagen as Martha and Arthur Hill as George in the original stage production in New York (1962).

Photo: Everett Collection / Rex USA/Copyright (c) 1962 Rex USA. No use without permission.

Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton in the film adaptation (1966).

Photo: ? Corbis. All Rights Reserved.

Alan Dobie and Rachel Roberts in an English production (1969).

Photo: Central Press

Kathleen Turner and Bill Irwin in New York (2005).

Katja Riemann and Peter René Lüedicke in Germany (2011).

Photo: Britta Pedersen/? Corbis. All Rights Reserved.

Tracy Letts and Amy Morton in Chicago (2011).