Cowboy Pizza anchors Clinton Street’s southernmost cluster of gentrification, about a block away from the La Guardia Houses. Its distressed picnic tables, soundtrack by Bon Iver, and framed photos of the bad old Lower East Side might recall the set of your typical Jesse Eisenberg vehicle, and in fact it’s one of the actor’s favorite lunch spots. Nervously cradling a slice on a recent frigid Sunday, he’s wearing the same navy cap, two-tone hoodie, and maroon New Balances his character dons in The Revisionist, Eisenberg’s second outing as a playwright. Co-starring with him is a more uptown class of celebrity, Vanessa Redgrave.

Eisenberg and I had our first, wide-ranging chat two days earlier in a Cherry Lane Theater dressing room—maybe too wide-ranging, because this time he’s brought along a chaperone. His close friend Lee, 43 to Eisenberg’s 29*, shakes hands and ebulliently offers his last name: “G as in gorgeous, A as in amazing, B as in booyah, A as in … amazing, Y as in yes!”

Eisenberg and Gabay met through their mutual friend, the actor Paul Dano. They spend most of their time together watching basketball, talking about basketball, and playing basketball. “Jesse has a good offensive game, but his defense could be fixed,” says Gabay, who’s taken to calling me “Bo.” “His rebounding skills are terrible.” Judging by his performance in interviews, Gabay seems best at blocking and running out the clock.

“I’m trying to protect the instrument,” Eisenberg parries, in the blinky, rapid-fire patter so familiar to fans of the archetypal Eisenberg role. He’s made his career as the younger alter ego of a parade of geek auteurs—The Squid and the Whale’s Noah Baumbach, Adventureland’s Greg Mottola, Woody Allen in To Rome With Love—culminating in the Oscar-nominated part of a real-life geek, Mark Zuckerberg, in The Social Network. Now, as a playwright, he’s written two avatars of his own, both of whom he’s played himself: pathetic, sycophantic Edgar in 2011’s Asuncion and pathetic, selfish David in The Revisionist.

Gabay paints a picture of the real Eisenberg as a brainy Everyman, more confident than his characters but no cockier than the average urban creative. “One thing that really says who he is: I remember on Oscar Night, when the other dude won, he sent me a text—”

“Wait, wait, what did I say?” Eisenberg interjects. Gabay whispers into his ear. “Oh, okay.” Eisenberg gives the go-ahead.

“He said, ‘I just want to remind you to feed my cat.’ And then he said—can I say the rest?” More whispering. “Then he said, ‘I was gonna remind you in a speech, but I was denied.’ That was cute.”

Gabay is clearly here to run interference, even at risk to his own “instrument.” When I bring up a big no-no—the older woman with whom Eisenberg lives in Chelsea—both of their eyes widen. When I ask if Eisenberg wants a family, he says, “Yeah, sure, yeah—and you?” seeming almost genuinely curious.

“If she’s mentioned, she gets mad at him—or me,” Gabay says, cutting us both off. “But that’s my problem with Angelica,” he adds—of his girlfriend, a pianist and yogi. “I want a family, and she doesn’t.”

After Gabay leaves, Eisenberg fiddles absently with a pen I’ve left on the table. Eventually, he brings up our earlier interview. “I don’t know what I’m doing here really,” he says. “I felt bad the other day after we left. I felt really guilty all night. Why did I say that stuff? Why did I talk about myself and my life? No one wants to know—maybe they do want to know, but I don’t want them to know … I wish I didn’t have to—I’m sorry. Yeah. And I shouldn’t have this kind of—yeah, it’s embarrassing, even now. Yeah, right.” He sniffs his artisanal pizza. He studies the pen. “I’m wondering whether I can extricate myself.” He runs out of words.

It says a lot about Eisenberg—his extreme decency and his extreme neurosis—that the avatars he’s created for the stage are sadder and less admirable than the sly, nebbishy parts he’s played in movies. But that’s always been the fascinating paradox of Eisenberg’s life, the source of his strange charisma. He got into acting because it gave him a script at a time when he never knew what to say. Now his growing success only leaves him more exposed, his skin as thin as ever. It’s a paradox he should probably explore further, especially now that he’s writing scripts of his own.

Eisenberg hardly ever watches movies, especially those in which he stars. Though he grew up idolizing Woody Allen, his first love was musical theater. Born in Queens and raised in New Jersey, he could easily write an indie quirkfest about his upbringing. His father drove taxis before eventually becoming a sociology professor. His mother worked children’s parties as what he calls “an unintimidating clown”—no scary red noses or floppy shoes. Big sister Kerri wrote musicals; baby sister Hallie Kate did a famous Pepsi ad campaign. Jesse began acting at 9 and spent his teenage Saturdays in midtown, soaking up such Broadway classics as Titanic, Footloose, and The Civil War. He’s recently finished his own musical, Me Time, which he describes as a parody of bridge-and-tunnel nineties fare like I Love You, You’re Perfect, Now Change.

Offstage, though, he was hardly a showman. Acting was his escape from a painfully awkward existence. He dealt with the transition to middle school “a little more histrionically than other kids,” he says, “and let it get out of control.” He had to skip part of the sixth grade for a home-school tutor, which “inadvertently perpetuated unhealthy behavior.” The only way to fight social anxiety, he realized, was to leave the house—and, eventually, New Jersey. He wound up transferring to Manhattan’s Professional Performing Arts School.* “I feel apprehensive to change,” he says now. “But if you can persevere and get over the uncomfortable hump, you’ll inevitably find something a little more satisfying than had you stayed home.”

Eisenberg vaulted his first great hump—a defining debut—at age 18, playing Campbell Scott’s endearing virgin nephew in the breakout indie film Roger Dodger. Three years later, in The Squid and the Whale, he embodied a Park Slope fraud-in-training, awkward but sharp-elbowed and just slightly smarmy. With nerd culture ascendant, the aughts were ripe for actors who could walk the line between stuttering and wit, passivity and aggression.

The next major hump came in 2009 with an odd pair of films. Adventureland, Greg Mottola’s follow-up to Superbad, was a perfect fit—which was the problem: “I became very self-conscious. It just felt very close.” With Zombieland, an apocalyptic farce, he had the opposite problem: the dread of anchoring a potential blockbuster. “It seemed like it could be a popular thing,” he says, “and I was just overwhelmed.”

He considered quitting acting, but decided instead to adjust his attitude. “I do something different now,” he says. “I don’t concern myself with thinking ahead to the finished product. I focus more specifically on what the character is experiencing. Once you relieve yourself of the very arbitrary and always punishing pressure of what an audience is expecting you to do, acting becomes a lot more fun and pure.”

Back at Cowboy Pizza, I asked Gabay how close Eisenberg is to his twitchy roles. “Jesse’s a lot more confident in real life—he has a vision, he’s strong,” said Gabay. “And unfortunately, whatever the powers that be, who put people in movies …”

“No,” Eisenberg interrupted. “Don’t say it—no. I don’t know.” Eisenberg later asks me to leave out Gabay’s aborted rant on typecasting, because “I don’t watch the movies, so I don’t know how I’m perceived in them.” Never mind that he’s written two of his own socially stunted characters. Any attempt to group them together will box Eisenberg in—as an actor and a person. “It’s gonna be reductive in a way that is not in line with how I see myself.”

Eisenberg concedes that his part in the forthcoming film Now You See Me feels refreshing: a magician-showman in a dystopian Las Vegas, clad in shiny suits, a sleek goatee, and some very grown-up cheekbones. The role has even bled into his real life. Eisenberg’s trademark curls were straightened for the movie with “poison,” as he puts it. But bits of the old Jewfro are reemerging like sidewalk weeds. When Gabay and I begin discussing the new ’do, Eisenberg again interjects: “That’s enough. Who cares about it? It’s stupid.”

In writing, Eisenberg’s screw-the-audience attitude adjustment came even earlier. In his early twenties, he tried to write romantic comedies and spent months in fruitless rewrites. He sent a script to Bob Odenkirk, hoping the comedy writer would pass it on to Adam Sandler. “You don’t need to write this,” Eisenberg remembers him saying. “You should write something personal.” So Eisenberg shifted to plays, which he eventually showed to David Van Asselt, the artistic director of the Rattlestick Theater. “His notes were geared toward making it more true to what it was,” says Eisenberg, “rather than placating an audience.”

What inspired his first produced play, Asuncion, was getting jumped on a late-night bike ride with Gabay in 2007. They caught one of the muggers but decided not to prosecute. Gabay teaches Brooklyn kids headed for juvenile detention, and Eisenberg often pops into his classes to read from audiobooks he’s recorded. (Repeat offenders who see Gabay often ask after “J-Dog.”)

Soon after the scrap, Eisenberg told this magazine that it was “more than understandable” that disadvantaged kids would beat him up. Someone wrote him a letter calling him an “ignorant, racist idiot,” blinded by political correctness. Agreeing, he gave the incident to Asuncion’s Edgar, a college grad so naïve that he assumes his Filipina sister-in-law is a mail-order bride.

“I don’t think [Asuncion] went completely into the places where he wanted to go,” says Van Asselt, “but there’s plenty of fascinating stuff in there.” Rattlestick generally commits to two plays by a newcomer, because a writer needs “the freedom to fail,” and Eisenberg was no exception. “I want to push him a little bit to become that writer that I think he can become.”

When Asuncion opened at the Cherry Lane Theatre in the fall of 2011, many reviews noted its sharp dialogue but also its gossamer plot. Then the Times’ Charles Isherwood cited it in a blog post on actors turned playwrights, concluding, “I would hate to see the not-for-profit theaters … start turning their stages over to marginal plays that stand out from the pack only because the playwright’s name might sell a few tickets to fan-club members.”

When I tried to read Eisenberg that quote in his dressing room, he flinched and begged me not to. But he defended himself: “I’ve tried to rewrite [plays] for dumb theater companies that don’t even have a theater, that don’t accept the changes I made for them anyway. This is not happening rashly.” A couple of days later, at Cowboy, he says my questions were hostile; when I explain why I asked, he unleashes a string of Eisenbergese: “I hear what you’re saying. Yeah, yeah, I guess so, I guess so. Yeah, I guess so. Yeah, I see what you’re saying. I guess so. I mean, I’m not, like, Lance Armstrong. But I understand.”

The Revisionist was actually the first play Eisenberg showed Rattlestick five years ago, and it’s been intermittently workshopped since then. It’s a big step up from Asuncion, if not a quantum leap. Eisenberg plays David, who’s written one successful novel but just missed the revision deadline on a new one that his publisher hates. He jets off to Poland on the pretext of visiting a distant, elderly cousin, a Holocaust survivor. She wants to bond, but he prefers to smoke pot in her threadbare guest room while pretending to revise. Eventually, their relationship thaws and long-buried horrors surface, breaking through David’s pretension.

The Revisionist sprang, like Asuncion, from Eisenberg’s guilt. He was visiting Venezuela in 2004 when the tsunami hit Indonesia, and a British traveler shamed him for not being able to locate Sri Lanka on a map. “You fucking ignorant idiot” is how Eisenberg remembers the exchange. David is that idiot. Maria, his cousin, is based on a beloved great-aunt, as well as some relatives Eisenberg met on a real trip to Poland.

For Maria, Eisenberg set his sights on Redgrave after seeing her in the intense, mournful monologue The Year of Magical Thinking. After an agent sent her the script, Redgrave came immediately onboard. “It’s just incredible, brilliant,” says the actress, who’s only seen Eisenberg act in The Squid and the Whale. “I always look for the play, and the rest follows.” They met in London and talked for several hours—“about everything,” she says.

Van Asselt and Revisionist director Kip Fagan have advised Eisenberg not to star in his work—“to sit outside the process,” Van Asselt says. Eisenberg says he’d prefer not to be in a third play he’s already written. Many actors read for the part of The Revisionist’s David, including Girls’ Christopher Abbott. But after Redgrave signed on, Eisenberg had to have it. “I’m still too close to it to relinquish that kind of control,” he says.

Redgrave only met me for eight fleeting minutes at the theater, on a break from rehearsals with Eisenberg. Every morning she brings in new research on her character’s background. She’s even suggested a key change in the script; suffice it to say, as Fagan does, that it “increases her character’s culpability.” As a playwright, Eisenberg was perfectly willing to relinquish control—at least to Redgrave.

“This is a difficult play,” she says, “all the more so because it’s also a very funny play. So the process is difficult, but the working is easy—the being together, responding to each other, listening to each other. It appears like rain when you really need it, like a good nourishing rain.”

“They speak each other’s language, they get each other’s humor, and they understand each other’s rhythms,” says Fagan. There’s no way to witness the interaction, because Redgrave doesn’t allow press at rehearsals. There’s that, too, in their odd-couple mind-meld. Eisenberg would love to limit his public exposure to eight-minute interviews. That’s one of the reasons he bikes everywhere; he’d rather risk a car door to the head than a subway Instagram spy.

But Redgrave no longer needs the attention that Eisenberg does. All of her uncomfortable humps are behind her. Eisenberg’s latest, playwriting, may be his biggest since the sixth grade. When I ask Gabay about his friend’s weaknesses, he ventures beyond Eisenberg’s rebounds. “He thinks too much,” Gabay says. “And, um, not self-deprecating, but—he’s cautious.”

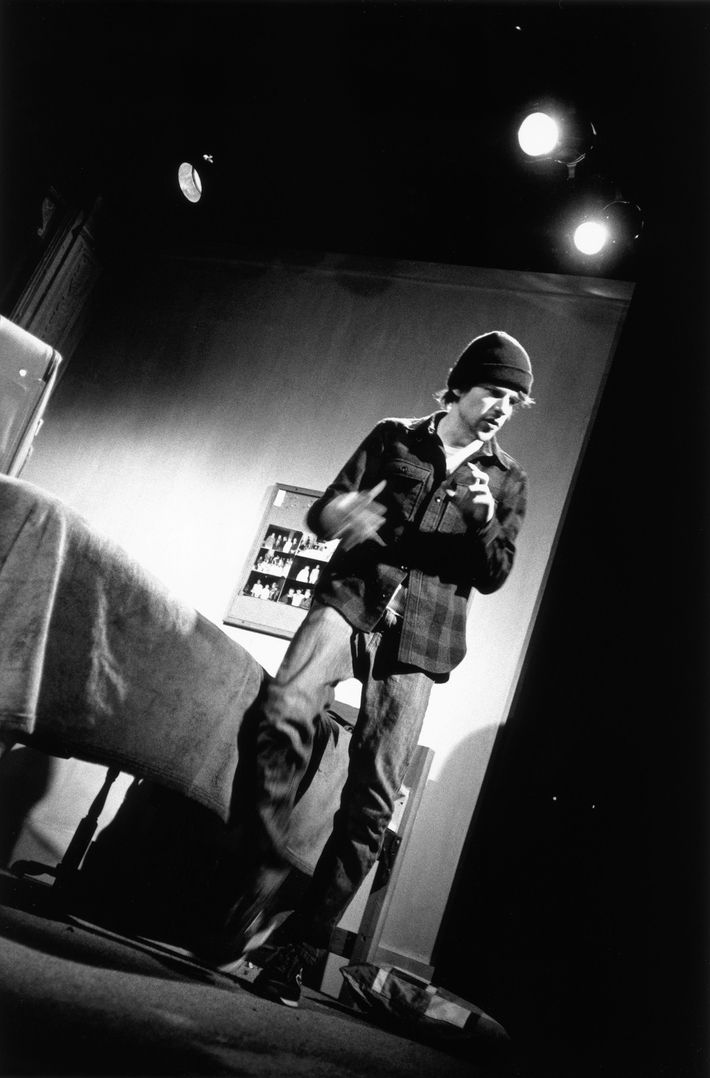

There is one brief rehearsal I’m allowed to see, a “fight rehearsal” that doesn’t involve Redgrave. In the scene, Eisenberg’s character confronts a surly Polish cabdriver, Zenon, played by Dan Oreskes, and they fight over a suitcase. It’s a telling moment for both the character and his author-portrayer, both of them too tentative about the impact they make on the world.

David is supposed to push past Zenon in a rare outburst of rage. Eisenberg attempts a two-handed open smack to the chest of Oreskes, who towers over him. “Get the fuck out of my way,” Eisenberg says—then breaks character—“Oh, sorry.”

“No, perfect, that was perfect,” says Oreskes, who’s barely budged. “And you’ll get some of that in a minute,” he jokes. Zenon will soon throw him against a wall.

“Yeah,” Eisenberg quips. “So when I push too hard, I’ll know!” Everyone laughs, and they try it again.

*This article originally appeared in the February 18, 2013 issue of New York Magazine.

* The post originally incorrectly listed his age as 28, not 29 and his high school as the High School of Performing Arts, not the Professional Performing Arts School.