Happy birthday, modern America! For all practical purposes, you were born 100 years ago this month. After February 17, 1913—the opening of what’s now simply called the Armory Show—you have never been the same. Thank God!

Originally called the International Exhibition of Modern Art, the show included around 1,200 works of art by more than 300 artists. Two thirds of the pieces on view were by Americans. Staged on the drill floor of the new 69th Regiment Armory on Lexington Avenue and East 25th Street, the show afforded America its first in-depth look at the art of Picasso, Braque, Duchamp, and many others. (Today’s Armory Show, the art fair held annually on the West Side piers, is unrelated.) By the time the show closed on March 15, 70,500 people had poured through. The last day’s attendance was said to be 10,000. When it went to Chicago after that, the attendance was estimated at 188,000.

How significant was the show? Salon impresario Mabel Dodge wrote to Gertrude Stein that it was “the most important public event … since the signing of the Declaration of Independence” and predicted it would cause “a riot and a revolution and things will never be the same afterwards.” One New York critic wrote that “American artists did not so much visit the exhibition as live at it.” Albert C. Barnes, Henry Frick, and the Met bought some of the work. The founding of MoMA, the Whitney, and much else stems directly from those 27 Earth-shaking days. And you can revisit them right now in Montclair, New Jersey: Thanks to the acumen of curators Laurette McCarthy and Gail Stavitsky and the foresight of one little institution that could, the Montclair Art Museum has mounted a small, smart, brassy show. Here, a tiny tip of the iceberg is on view: 40 works that were actually in the show by 38 artists, mostly Americans. Why no major New York art museum tried to do this is baffling.

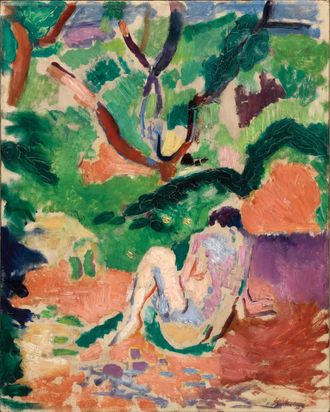

Why did the original set off such an atom bomb of anger? The New York Times headlined one story “Cubism and Futurism Are Making Insanity Pay.” (There were no Futurists on hand. They were invited, but their consigliere, Filippo Marinetti, wouldn’t mingle with Cubists.) The press lambasted artists as “paranoiacs,” “degenerates,” and “dangerous.” The show was like “visiting a lunatic asylum,” filled with the “chatter of anarchistic monkeys.” The art was “epileptic.” Conservative American painter William Merritt Chase clucked that Matisse was a charlatan. Indeed, Matisse came in for especially harsh criticism. (More, even, than Duchamp’s sensation-causing Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2.) When the show reached Chicago, art students tried Matisse in absentia for “artistic murder, pictorial arson … criminal misuse of line,” and burned copies of his paintings. They tried to burn him in effigy, too, but were thwarted by local authorities. Critics opined that Matisse’s were “the most hideous monstrosities ever perpetrated” and “poisonous.” The former president Teddy Roosevelt barked that the art was “repellent from every standpoint,” and concluded that there’s “no reason why people should not call themselves Cubists, or Octagonists, or Parallelopipedonists, or Knights of the Isosceles Triangle … one term is as fatuous as another.”

A hundred years later, the received wisdom is different, but it’s still wrong. Most art historians today say that, in 1913, American artists were yokels, and the Armory Show marked the arrival of European sophistication on our shores. Although the Montclair curators accept that America was behind the curve, they also note that Americans knew change was afoot. By 1913, they were—apart from the academicians—keen on the European vanguard. Numerous Americans had studied, worked, or exhibited in Europe, including many women. (Almost 20 percent of the Americans in the Armory Show were female—a better ratio than we often see today.) Between 1907 and 1913, there were more than 60 exhibitions of “modern art” in New York. In 1905, Alfred Stieglitz had opened a tiny gallery at 291 Fifth Avenue that had almost as big an effect as the Armory Show, championing Americans like Georgia O’Keeffe, John Marin, Paul Strand, and Marsden Hartley, who is my favorite prewar American painter. Stieglitz also showed Europeans like Picasso, Matisse, and Brancusi.

The Montclair exhibition is a blast of fresh scholarship and a godsend of celebration. It also reveals that the original show was uneven. Much of what’s on view is competent and striving but conservative. You’ll see pictures of puppies and sunsets, rustic towns and mystic seashores. Just as the Armory Show ruthlessly exposed the difference between what “modern” meant in Europe and what it meant here, the new show does the same. In the U.S., realists like William Glackens, Robert Henri, and George Bellows were called “modern,” but only because of their subject matter—vernacular street scenes, prostitutes, boxers—and Manet-like greasy paint and post-Impressionist brushwork. All but a very few American artists were trying to be “modern” without Cubism, Fauvism, and Futurism, and most of them fell into obscurity as those isms made their way across the ocean to us.

That said, there are lots of yummy exceptions. I love John Marin’s mad quasi-Cubistic watercolor of New York’s St. Paul’s; Kathleen McEnery’s nudes standing in the super-condensed flat space of Picasso’s Blue Period; Oscar Bluemner’s flat planes depicting the Hackensack River; Edward Hopper’s sailboat, which isn’t modern but already shows signs of the implacable isolation that would later make his paintings quake; and Maurice Prendergast’s street scene, probably the most fully realized modern picture here. But mainly you’ll see why the Armory Show changed everything—why American art altered its essential course. The lessons of the Armory are the ones all moments of change provide.

I’ve lived through a couple of artistic shifts and have gleaned some intelligence about which artists get left behind. They’re often the ones who don’t press extra-hard on their work. I’m not talking about changing one’s core or following fads for their own sake. I mean questioning what’s contemporary about what one is saying. In the early eighties, I watched excellent artists of the seventies fade away as they couldn’t accommodate the ideas of irony, feminism, and neo-conceptualism that were taking the stage. They refused to, or couldn’t, engage with the culture, and that culture passed them by.

Legions of American artists were lost, too, after the Armory Show. But many adjusted to the shock, discovered a strong fresh footing, and found a new faith in the powers of art. The Montclair show is a cautionary tale to artists everywhere to be alert to moments like this—to have the wherewithal to perceive metapatterns reforming, tendencies in motion, and your own insides being twisted inside out.

The New Spirit: American Art in the Armory Show, 1913; Montclair Art Museum, Montclair, New Jersey; Through June 16.

*This article originally appeared in the March 4, 2013 issue of New York Magazine.