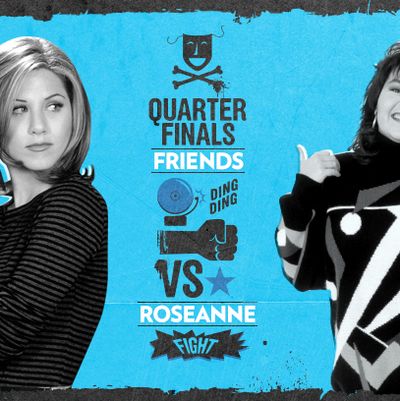

Vulture is holding the ultimate Sitcom Smackdown to determine the greatest TV comedy of the past 30 years. Each day, a different notable writer will be charged with determining the winner of a round of the bracket, until New York Magazine TV critic Matt Zoller Seitz judges the finals on March 18. Today is the second match of the quarterfinals, with critic Ken Tucker pitting Friends against Roseanne. Make sure to head over to Facebook to vote in our Readers Bracket, which has already veered from our critics’ choices. We also invite tweeted opinions with the #sitcomsmackdown hashtag.

To compare and contrast and ultimately declare a “winner” between Friends and Roseanne means grappling with a bigger issue than the differences in quality between two sitcoms. Indeed, what we must grapple with here are two interpretations of cultural excellence that have bedeviled art, literary, and music critics long before it drifted down to TV criticism. I speak, of course, about the Unruly Masterpiece versus the Well-Wrought Masterpiece. Moby Dick, say, versus The Great Gatsby. Infinite Jest versus White Noise.

For the purposes of this argument, though, let’s dispense with the label “masterpiece.” Both Roseanne (1988–97) and Friends (1994–2004) are superb television series, but neither is a masterpiece in the unified, complete sense that The Wire or Lisa Kudrow’s second series, The Comeback, are worthy of that title. Nevertheless, both shows were and are, when watched now, exceedingly funny, and fascinatingly divergent examples of how sitcoms with ensemble casts come to be experienced as families — either in the literal sense in Roseanne or in the tight-buds-hanging-out sense in Friends — with whom we form tight bonds.

Roseanne was conceived as a showcase deriving from Roseanne Barr’s stand-up comedy act. The self-styled “domestic goddess” — “a term of self-definition, rebellion, and truth-telling,” as Roseanne would later define it — became a hit with Johnny Carson and on other talk shows for her braying jokes about how tough it is to be a woman, a wife, and a mother. She was at once part of a tradition — her immediate forebears were Phyllis Diller and Totie Fields, stand-ups who wielded aggressive sarcasm and declined to fit conventional showbiz standards of attractiveness — and the creator of her own, new paradigm. While other stand-up comics before her (Redd Foxx, for example) and after her (Tim Allen) had sitcoms built around their nightclub personas, Roseanne took the care and feeding of her TV-show image to a new level of creative control.

If the show had the look of a conventional sitcom — Lanford, Illinois, housewife and menial-job holder Roseanne Conner, married to John Goodman’s Dan Conner, their three boisterous children, and her sister Jackie (Laurie Metcalf) — Roseanne soon made the Conners’ ratty living-room sofa and its crumb-encrusted kitchen table the sites for discussions and arguments about class, child-rearing, labor politics, sexual identity, and (as the seasons went on) anything else that was on Roseanne’s restless mind. A ratings hit from the start, the show became a vehicle for Roseanne Barr/Pentland/Arnold/Thomas to exert a power she never felt she’d had in her life, and at times her behind-the-scenes run-ins and firings with producers and writers threatened to overshadow the achievement of what she did.

Seen now, Roseanne remains an uneven but engrossing mishmash of sitcom one-liners about lazy husbands and surly teens, and acute glimpses into revolving-job lives (at various times Roseanne worked on an assembly line, in a beauty parlor, a bar, a fast-food restaurant, a department store, and a lunch counter) that seems more timely now, in the present economy, than ever. Among other things, the show is striking for the way it constantly plays with sexual identity. In the 1990 Halloween episode, for example, her son D.J. (played by Michael Fishman) wanted to go out trick-or-treating as a witch, which freaked out Dan (”Boys are supposed to be warlocks!”), and Roseanne dressed up as a very convincing male lumberjack. The half-hour reached its peak with Goodman defending his bearded wife from being punched out in a bar. Looking the potential attacker straight in the eye, Goodman snarled, “Hands off. That’s my husband over there!”

Through the sheer force of its star’s personality and the attitude that permeated the show, Roseanne as a studio-audience, multi-camera sitcom achieved the kind of intimacy and self-awareness that later characterized single-camera shows such as The Office and Curb Your Enthusiasm. Beneath her persistently and gloriously crude exterior, Barr was shrewd-with-a-mission: “I wanted [Roseanne] … to explode the traditional media image of a woman. And family. And work.” At the height of Roseanne mania, she was our Elvis Presley — a unique artist who is unable, but also unwilling, to escape the constraints of class, because to do so would feel like a betrayal. Like Elvis, she has created two huge audiences: one that thought of her as a figure for derision, and another that reveled in the associative pride of her achievements.

Friends, too, began its existence looking more conventional than it proved to be. In 1994, a show about a bunch of attractive yuppies sitting around talking — what did that make viewers think of? thirtysomething, Seinfeld, and Mad About You, among many other, lesser shows. Created by writers Marta Kauffman and David Crane (Dream On), Friends was custom-made for NBC as a show that would appeal to the young demo that was starting to dominate advertisers’ minds as the sole audience that needed to be wooed for maximum profit. But fairly quickly, Friends evinced a captivating polish and style (much of it because of the regular direction of James Burrows) that made it operate like a first-rate Broadway farce, complete with slamming doors, twisty plots, and intricately strung-together jokes. In other words, necessity (in this case, the quest for ad dollars) became the mother of invention — art, even. Kauffman and Crane’s writing and casting and Burrows’s direction gave Friends a momentum and charm that permitted the cast of mostly unknown actors the time to settle into the roles they are spending the rest of their careers trying to divest themselves of.

The six actors were all relative unknowns: Jennifer Aniston had been frequently brilliant on Fox’s short-lived sketch-comedy show The Edge in 1993, and Courteney Cox had some recognition for bopping with Bruce Springsteen in his “Dancing in the Dark” video and playing Michael J. Fox’s girlfriend for the last two seasons of Family Ties. For a brief time, Cox’s Monica was the primary character, but before long the actors’ chemistry and individual talent turned them into a cast of equals. Aniston brought a prickliness to Rachel that belied her prettiness. Matthew Perry managed to find layer after subtle layer in Chandler, and ended up playing the most complex self-loather on TV. Matt LeBlanc was that rarity, a hunk with a gift for deadpan comedy; his aspiring actor Joey might have started out as just a lummox, but LeBlanc turned him into the ne plus ultra of lummoxes. David Schwimmer — who played PhD-holding Ross with a mixture of intelligent-man condescension and social-idiot neediness — made hangdog depression seem like a new notion in comedy. Lisa Kudrow’s Phoebe, imported as the identical twin of a ditzy character she had played on Mad About You, started out as something of a sixth-wheel novelty act until Kudrow made her a deeply eccentric woman whose kindness and apparent innocence masked a shrewd understanding of human nature. As for Cox, she played straight woman to this bunch with alluring modesty.

Friends operated on two levels simultaneously: as a mass-audience big-network crowd-pleaser sitcom and as a private club for initiates who’d followed the mythology-before-it-was-called-mythology of the show, and therefore knew things such as the “way of giving the finger” that Monica and Ross had made up as children. The series was capable of a finely grained romanticism, as in one of my favorite episodes, the fourth-season “The One With Chandler in a Box,” in which Joey, angry at Chandler for kissing his girlfriend Kathy (Paget Brewster), consigns Chandler to remain silent while locked in a box in the apartment. Kathy breaks up with Chandler while he’s in the box, and his continued silence, even as his love affair is dissolving, moves Joey to both forgive his friend and urge him to pursue Kathy. In many ways, Friends presaged the late-nineties rom-com trend in movies, often doing it as well as any feature film.

Unlike Roseanne, Friends became slicker, more streamlined and more knowing about its endgame (the pairing off of Ross and Rachel, then Monica and Chandler), as it proceeded. By contrast, Roseanne went reliably haywire. The Conners won $108 million in the Illinois lottery, and the series took on a surreal randomness that many people find impossible to square with the shrewdly realistic show that Roseanne had been. To me, the show’s final season was like Roseanne’s crotch-grabbing rendition of ”The Star-Spangled Banner” at a 1990 San Diego Padres game: It was a shock, I winced, but I was thrilled by the combination of rage, guts, and screw-’em-all joy that compelled her to do it.

I almost can’t believe I’m arguing from the position I’m about to take. In lit and music, I’m a Tidy Great Works man: I prize the meticulous class-bound novels of Anthony Powell and the precise concision of Chuck Berry and Steely Dan over the sprawl of Gravity’s Rainbow and Nirvana and the best of the Grateful Dead. But my head, gut, and eyes tell me that Roseanne is the Great White Whale of Television, the Moby Dick of Vaginal Politics, and for that it deserves to move on in this competition.

Winner: Roseanne

Ken Tucker is a cultural critic who has been writing about TV for, like, years. You can hear him regularly on NPR’s “Fresh Air.”