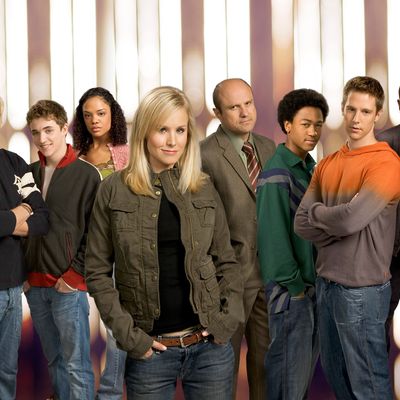

It only took eleven hours for Veronica Mars fans to collectively bid the $2 million on Kickstarter that would get a movie sequel made to Kristen Bell’s defunct WB show: While Warner Bros. would pay for distribution and marketing, the contributions would be funding all of the production costs. Yesterday, it became the fastest Kickstarter project to hit $1 million (doing so in just under four and a half hours), cementing hopes that, after more moderate success for original projects like Charlie Kaufman’s stop-motion film ($406,000) or Amanda Palmer’s Theatre Is Evil ($1.2 million), the site was now officially a viable power-to-the-people tool that could wrest decisions and creative dilution from micromanaging Hollywood executives. However, before proclaiming a new dawn in which studios and music labels atrophy as decisions are completely commandeered by artists and audiences, it’s important to point out that Veronica Mars is a very specific case. It crosses the streams of the Internet’s two most powerful by-products: overpowering nostalgia and impatience.

It may seem strange to call love of Veronica Mars “nostalgia,” since it only went off the air six years ago, but the window between pop-culture farewells and moony, idyllic remembrance has shrunk so much that the lag between sign-offs and sanctification is about eight months, depending on the number of catchphrases the show in question spawned. Just as online comments sections are now forums for people to voice the most polemic versions of their own beliefs, so too has the internet escalated people’s public and mutually enabled love of the past, be it from their childhood or last year. Old shows aren’t great, they’re the best show in the world ever! (See comments from fans of losing shows in our Sitcom Smackdown: The anger was so vitriolic that you would think the match had been “Tuna sandwich versus Your Beloved Grandmother. Winner: tuna sandwich!”)

Fans want their favorite shows to come back with a passion that goes past bemused fantasizing. The increasing occurrence of cult shows or long-dormant franchises returning from the dead (Family Guy, Arrested Development, Star Wars, Indiana Jones) has made pop-culture reincarnation a truth. Get the grass rooted, and it’ll happen: Get us more Pushing Daisies, Deadwood, Gilmore Girls! And as a result, fans get all the more engaged in the quest, to the point where they’ll chip in to make it happen if they have to. They are as desperate as if they were addicts suffering the D.T.’s: They were entwined with these shows, deeply invested in the story that was abruptly cut off.

But if Veronica Mars creator Rob Thomas and Kristen Bell announced they were collaborating on an unrelated project, the donations would be far less. It’s the difference between telling someone “Give me $100 to try cocaine for the first time” and “Give me $100 for more cocaine.” Yes, artists with devoted fans will always be able to rally them to open their wallets for new, interesting work. But these same artists will get their acolytes to empty their bank accounts if they promise more of something familiar. Put another way: Had Martin Scorsese tried to crowd-fund his upcoming movie Wolf of Wall Street, he would have made a scrappy indie. But if he put Goodfellas 2 up on Kickstarter, he might raise enough to set it in space.

Fans of defunct TV shows have been empowered by their previous successes. (“You won’t give me more Bluth family, Fox? Fine, we’ll take that shit to Netflix and then you’ll be sorry! Don’t worry, we’ll visit you and the rest of network TV in the retirement home, where you’ll be playing pinochle in the common room with an old Betamax and the cast of Silk Stalkings!”) But it’s more than that: A generation accustomed to streaming what it wants when it wants, and being able to instantly summon and binge-watch entire seasons in a week, gets agitated when “more” is out of reach. It seems irrational that you can’t have more; it’s as if the timeline has stalled. Where is the button that teleports all the actors back onto my screen and makes them act out new stories? We’ve already done away with all the other limits of time and space (screw you, TV schedule), so why have we suddenly hit a wall? So when someone gives us an option to get more, the reaction is “Finally! Yes, take what you need, just get this going again!”

A debate has ensued about whether it’s ridiculous for fans to have to pay twice (lower-tier donors don’t get the free DVD or digital version) to subsidize a movie that a major studio stands to profit from. But realistically, the studio is not likely to make much of a profit on a Veronica Mars movie. The 43,000-plus donators (as of Thursday at noon) do not necessarily portend huge numbers at the box office, even if they all bring three friends. (When Universal* capitulated to the constant stomping for a Firefly movie and made Joss Whedon’s Serenity for $39 million, it only brought in $26 million in the U.S.)

Internet nostalgia is a double-edged sword. The very escalating group pining that happens in relation to old projects does not necessarily mean they want to see more; as Matt Zoller Seitz wrote, beloved shows should remain dead. Nostalgia is grasping for the impossible: You don’t want more of what you remember fondly; you want to be back at the time when you enjoyed it, which is an impossibility. Fervent campaigning for more, more, more is really a rally for time to move backward. The disappointment of the Star Wars prequels wasn’t entirely the fault of the subpar movies, it’s that adults would never be able to see them with the same wonderment that they did when they were kids and played Luke and Han in their backyards. It was fun to beg for more Indiana Jones adventures, but Kingdom of the Crystal Skull was unsettling: Old Indiana Jones? We’re old — I don’t want to be reminded of that! Make him young; make us young! Witness the mass mind-losing over Girl Meets World. Once the thrill fades of first seeing the old Boy Meets World faces reunite, will there be any reward to seeing them deliver TGIF-caliber humor? And if it suddenly becomes smart, adult comedy, wouldn’t that feel just as wrong?

But no matter history; the prospect of any old show returning is always greeted with prayers-are-answered hosannahs and a just tell us what we have to do battle stance. Ponce de León never faltered in his quest for the Fountain of Youth; Kickstarter is our path to that magical oasis.

* This post originally mistakenly credited Serenity to Fox, not Universal.