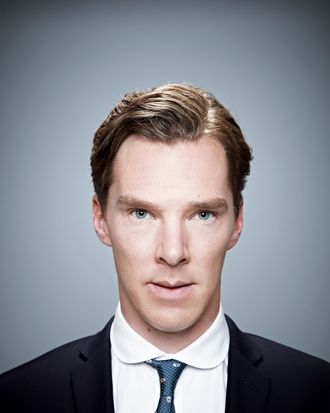

I meet Benedict Cumberbatch the afternoon after an awkward appearance on Letterman, where he was promoting his part as John Harrison, an intergalactic terrorist, in J. J. Abrams’s Star Trek Into Darkness. It’s a summery spring day in New York, and we’re on the patio of his room at the Bowery Hotel. Cumberbatch—his dead-white complexion shaded by a newsboy cap—is “chuffed” by his posh digs; it’s his first starring role in a blockbuster, and he’s not used to this level of star treatment—well, from everyone except David Letterman, who has not, apparently, been following the actor’s rise as avidly as the actor’s Internet fan club, the Cumberbitches. Not only did Cumberbatch have to follow an animal act, but Letterman, who began by referring to Star Trek as Star Wars, asked his guest—a veteran of twenty movies, including Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy and War Horse—if he was new to major motion pictures. (The actor, being the polite, Harrow-educated Brit that he is, jumped in to save his host: “This major? Yes!”) I tell Cumberbatch that, given Letterman’s cluelessness, I was surprised there weren’t the usual efforts to wring a laugh from his name.

“Well, since he couldn’t even say it,” says the actor. “At one point, before I came on, he announced me as ‘Benedict Cumber… ,’ and his voice sort of trailed off. My friends said, ‘What the fuck was that? It was like his batteries ran out.’ But that’s the sort of thing that’s been happening here, where I’m not as well known,” he continues. “It’s strange to be 36 and still explaining the weirdness of my name.”

Cumberbatch is very well known in Britain and practically a superstar online thanks to his Golden Globe–nominated role as Sherlock Holmes in the BBC’s high-tech, modern-day Sherlock, which debuted in 2010. (It’s more of a cult hit here, where it airs on PBS.) “I generally don’t look to see what people are saying about me,” he says. “But when the show started to explode in Britain, and I was reading stuff online, I started to think it was real. I thought I’d walk outside my door and hundreds of people would be lining the streets, cameras would be flashing. I quickly realized the audience was virtual.”

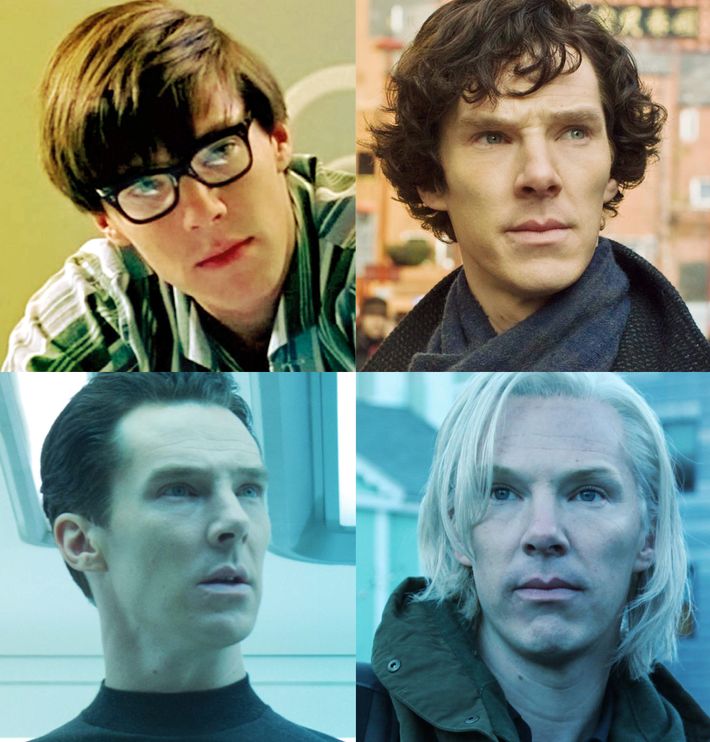

Well, not really. Those are flesh-and-blood fans huddled outside the London locations of Sherlock, which is currently shooting its third season. “That’s why I have this ridiculous length and color,” says Cumberbatch, tugging at his black hair (he’s naturally auburn). “Every time I take Sherlock out of the box, I have to put the fucking hair dye on.”

This is a man who lives for details. His breakout role in Britain was the young Stephen Hawking in the BBC’s 2004 film Hawking. It introduced one of his great talents—humanizing the analytical—and a reputation for precision and obsessive preparation. To wit, this description of his Star Trek villain, a genetically engineered superman: “I wanted Harrison’s voice to have something slightly manufactured and odd, that sounded test-tube-made, where every word was sort of etched,” Cumberbatch explains. “I was keen to make his violence quick—not balletic, but purposeful. And his physique—he’s not Bane, he’s not this unsurpassable physical entity. He’s a warrior, a spearhead—someone who just carves his way through and doesn’t stop. There had to be emotion in the movement as well, and when he was at rest, it was more reptilian.”

Cumberbatch prefers the hows to the whys of acting, and he found a kindred spirit in Meryl Streep, his co-star in this fall’s August: Osage County. “I asked her how she approached the multiple layers of her part,” says Cumberbatch. “And she said, ‘I don’t know. I don’t have a process. It changes with every job, doesn’t it?’ And I thought, Oh, thank God, to hear her say it. This whole thing about technique or method? It’s bullshit. People say, ‘Oh, you’re so precise.’ But within that I work very hard to give every part a heartbeat. I learned a lot from just watching Meryl in repose. It was a bit like a Sherlock deduction actually.”

Once people have digested the absurdity of his name, the next reaction generally goes like this: “Oh, yeah, he’s good. But he’s so strange-looking.” Letterman featured the Tumblr, Otters Who Look Like Benedict Cumberbatch, which the actor considers “utterly brilliant.” To my mind, his big, impacted features are more reminiscent of an Easter Island head—a near parody of good looks that can have the effect of making more traditionally movie-star handsome actors (say, Star Trek’s Chris Pine) look dull by comparison. They can also distract from the transformative physicality he brings to every part, from buttoned-up brainiacs (Christopher Tietjens in the recent BBC Two mini-series Parade’s End) to the more explosive demands of Danny Boyle’s 2011 stage production of Frankenstein, in which Cumberbatch and Jonny Lee Miller alternately played Victor Frankenstein and his creature.

What are the odds, I ask Cumberbatch, that you and your friend Miller would both end up playing Sherlock Holmes? (Miller is the star of the CBS hit Elementary.) “We laughed about it a lot,” he says. “I love his show. It’s a deviation, a beautiful and interesting one. Our Sherlock chimes much more with Conan Doyle’s original—I don’t think Jonny would mind me saying that.”

Where Cumberbatch’s Holmes is notably asexual (while still managing to be sexy), Miller’s is the opposite. Yet, curiously, the former has more chemistry with his Watson, played by Martin Freeman, than the latter has with his, played by Lucy Liu. Cumberbatch has a history of compelling rapports with his male co-stars. “I’m basically gay, is that what you’re saying?” he says with a laugh. No, it’s not sexual chemistry, just a more delicate version of male friendship than we’re used to seeing in American films, where relationships between bros tend to be warier and more superficial. “I see a similar tenderness between Kirk and Spock,” he says. “It speaks to the sort of friendship you’re talking about, and maybe that was part of my appeal for J.J.”

If Harrison is a bit of an enigma, the intentions of Cumberbatch’s next character, Julian Assange, were crystal clear. This time the challenges were less physical than moral. The script for November’s The Fifth Estate is based on two one-sided accounts that are not pro-Assange, a man the actor admires: “No matter how you cut it, he’s done us a massive service, to wake us up to the zombielike way we absorb our news.”

Though he and Assange have never met, Cumberbatch says the two had “a form of communication. He hates the idea of the film and asked me not to do it, and I said to him, ‘Well, somebody is going to do it, wouldn’t you rather it’s someone who has your ear, who could steer the film to a place that’s more accurate or balanced?’ The tabloid image of him, what he fears is going to be promoted—that weird, white-haired guy wanted for rape—is so far from what we did.”

Comparatively speaking, December’s The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug was just good, sweaty fun. Cumberbatch did his time at Peter Jackson’s motion-caption studio playing the titular, gold-hoarding dragon as well as the Necromancer and resents reports to the contrary. “It was publicized that I ‘voice’ Smaug, and I thought, Fucking hell. My voice, my motions—I worked my ass off to create that dragon!”

*This article originally appears in the May 27, 2013 issue of New York Magazine.