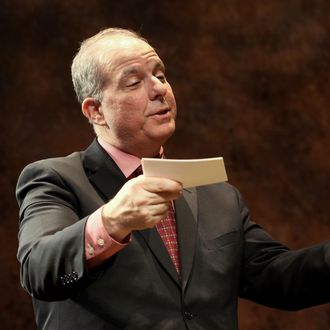

For the first time in eleven years, the hand on the tiller at Lincoln Center is changing. Reynold Levy, who raised staggering amounts of money and oversaw the $1.2 billion renovation of the campus, is retiring at the end of the year, and his successor, the Broadway impresario Jed Bernstein, now president of Above the Title Entertainment, inherits the next major construction project: the renovation of Avery Fisher Hall.* Bernstein spoke to Justin Davidson from the office that will become his on January 26, 2014.

Many years ago, Jane Jacobs predicted that Lincoln Center would isolate the arts on its own acropolis and suck the energy out of venues like Carnegie Hall and the theater district. You’ve watched the center get built and evolve into a much more open and busy organization, active in every season, indoors and out, and you’ve seen the city change around it, too. How do you think that relationship between arts center and city will continue to evolve?

I don’t think the arts are a competitive sport, so the more venues there are all around the city, the better. Lincoln Center is a jewel in the cultural world, and that means we have to be as involved with the city as we can possibly be. On Broadway my mission was to make all the constituencies feel that theater was part of their lives. I want to do the same here.

Lincoln Center is less a single organization than a collection of more than a dozen private fiefdoms, with their own audiences and often with conflicting agendas. Is that what the theater world is like, too?

Having theater owners, presenters, general managers, and producers from all over the country be part of the same organization gives me some insight into that. Sometimes it was easy to sing from the same prayer book, and other times it was much more challenging. If you can create a spirit of collaboration, that’s always the best way home.

You’ve got plenty of experience squeezing investors for commercial theatrical ventures, but now your job is going to involve getting people to give tens of millions of dollars every year — just because it’s the right thing to do. Is there a real difference between those two kinds of fund-raising, or is money always money no matter how you ask for it?

Getting people to be passionate about a play or about the mission of a nonprofit organization is at the heart of it. It’s important to understand the needs and motivations of donors — why they want to engage. In my teaching, I’ve developed a list of twelve different motivations for investing in Broadway shows, and I suspect there are at least twelve and more like twenty for investing in an organization like this. But you have to make people feel connected, they have to feel a sense of ownership of the place. The way you foster that is by being humble and accessible, and by treasuring the rituals that swirl around the place. At the same time, nothing is more off-putting than a place that has all these rituals and you don’t know who they are.

So how do you distinguish between valuable rituals and the off-putting ones?

Coming to Lincoln Center as a child, I was taught by my parents that if the music is playing, you don’t applaud. If the composer had wanted you to clap, he would have inserted a pause. And now of course in dance and certain operas, people clap when they want to clap. So how do you make people feel that they’re not doing the wrong thing? If you can be articulate about the mission and the goals you’re shooting for, that makes people feel comfortable.

“Live From Lincoln Center” has been instrumental in extending the LC brand for a long time now, but in recent years, the Metropolitan Opera has taken the technological lead with its HD broadcasts to movie theaters. Are there media and technology avenues that Lincoln Center should be taking advantage of?

The Met has definitely shown the way. Peter Gelb has been a genius both in the content of what he’s produced and the way he was able to make an argument to unions and subscribers that this was going to benefit everyone. The thing about digital technology is that if you don’t get out in front, if you don’t control the content and use it to innovate, you’re going to get run over. The rest of us need to catch up. Maybe it’s by creating a library of broadcasts, or by harnessing technology better to customer service problems like lost and found, or ticketing and marketing. But the other aspect of this is “phygitalizing” the campus with interactive screens, kiosks, things like that. Look, I was at a tennis tournament recently and, even when there were no matches going on, people were staring at a gigantic screen and reading other people’s tweets!

Obviously you have a longtime connection to theater. What’s the level of your personal interest in opera, classical music, film, or ballet?

I started coming to Lincoln Center when it was first built, and was lucky enough to be a middle-class kid who could see opera and ballet and classical music from an early age. I have no facility in these areas — I did play trumpet in middle school, and if you find the tape, burn it — but I have a crush on talent. Being around world-class artists, that’s the most exciting thing in the world to me.

Are middle-class kids growing up in New York City today going to the opera and ballet the way you did?

No, they’re not, and that’s one of the urgent issues we have to focus on. We’re losing a generation before we start. One of the things we learned on Broadway is that the likelihood of people going to the theater in their thirties depended on whether or not they had been exposed to it as a child. If you miss a generation, then you miss the next generation, too, and then there’s a downward spiral. I grew up with Leonard Bernstein teaching me about classical music on television. Today, symphonic music seems completely irrelevant to the average kid, so how can we make it accessible?

Is it really an issue of accessibility? Don’t they have just as much access to it as they do to any other form of entertainment?

If you grow up thinking, This thing is not for me; this isn’t part of my experience, and it doesn’t reflect anything I’m about, then it’s not really accessible. It’s up to us to build intellectual bridges to the next generation.

When you look around the world at other performing-arts campuses and facilities, are there any that make you envious, make you think, Yeah, we need some of that?

I haven’t looked yet — I mean, I’ve only been on the job an hour. But that’s one of the things on my agenda. I’m never too proud to steal.

* This post previously stated that Bernstein was currently the president of the Broadway League. He left that organization in 2006.