Everyone dreams of power. No one dreams of power more than children. No child dreams of power more than one who has been sexually abused.

Thus I discovered one evening to my delight, while home alone, a brand-new television program called The Incredible Hulk. It was 1978 and it was 8 p.m. and I was 9 years old. Four years had passed since the abusive episodes had occurred and I was now living in Pittsburgh with my mother in a one-bedroom apartment, small and shabby, furnished almost entirely with second-hand furniture. My mother slept in the living room and I slept in the bedroom, and two nights out of the week, sometimes three or four nights, it was up to me to put myself to bed. So I had grown quite accustomed by this time to trying to fend for myself. I had also grown accustomed to being generally bored, occasionally frightened, and always fatherless. Among the many subjects that were never addressed in our home, the sexual abuse was only one of them.

Into this void appeared the actor Bill Bixby on my thirteen-inch black-and-white television. Handsome, gentle Bill Bixby who, as the solitary Dr. David Banner, would soon undergo an astonishing physical transformation before my eyes. It was no small matter that Bixby had also starred as the widowed father in The Courtship of Eddie’s Father, a sitcom from the early seventies, which I had once watched in syndication after school — while home alone. The central premise for The Courtship of Eddie’s Father had generally revolved around 6-year-old Eddie’s clever attempts to find a new wife for his dad. The show was intended to be light, optimistic fare, but it was nearly unbearable for me to watch, beginning, most painfully, with the opening credits of Eddie and his father frolicking along a Southern California beach amid the theme song, “Best Friend.” I wanted to be Eddie, of course, who was little like me, young like me, with dark hair, and who had the great fortune of being in the presence of what was the program’s true prize: Bill Bixby. Still, I watched, as I watched everything, because the sound of the television was always a more desirable alternative to the silence of the apartment.

The Incredible Hulk was not optimistic fare. It was grave and treacherous, with the stakes being life or death. Physically unthreatening and burdened by a peaceful temperament, Dr. David Banner was in constant jeopardy of being set upon by those larger and more powerful than he. If nothing else, here was a television program that honestly reflected the natural pecking order of the world. Each episode found Banner, through no fault of his own, in yet another precarious situation, chained, caged, buried. But in the creation mythology of this show, i.e., the side effects of an overdose of gamma radiation, the natural order of things could now be turned upside down. I was too young, or too unobservant, to grasp the program’s formula: twice each episode Banner would be menaced; twice he would transform; never would he succumb. (I was also too young to perceive the poor acting and the overblown writing.) It was the repetition of the show’s scenario, with barely any variation, that made the viewing so compelling. As unsettling as it might have been for me to witness Banner imperiled again and again, it was ritual, it was cathartic. It was what I had to look forward to on Friday evenings as my mother prepared to depart. In short, I had found a way to experience what had happened to me years earlier, this time, however, with much different outcome.

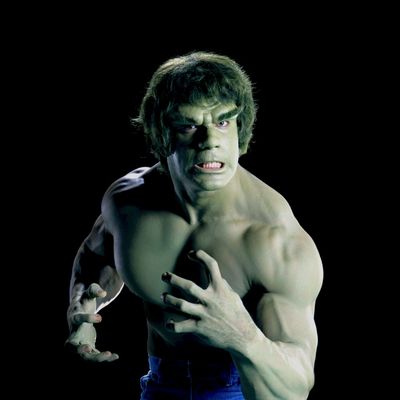

The metamorphosis came as a surprise and a relief each time. That stunning, sudden emergence of the alter ego — not a moment too soon — with the eyes turning white and the muscles bulging so tremendously that the clothes tore straight off. Out of one compromised body, emerged a second, stronger body, this one virile, with bare torso and enormous chest. Here was masculinity writ large. Also sexuality. Add to this, my inability to understand that there was a different actor playing the role of the Hulk, caused me to assume, as a matter of course, that what I was seeing was a product of special effects, through lighting or makeup, that somehow recast the slender, modest body of Bill Bixby into a magnificent, all-powerful physique. Nor was it consciously chosen, this transformation. It was not the result of actively donning a cape and mask to seek out justice like the other superheroes I loved — Superman, Batman, Spiderman, et al. Rather it was an involuntary response to outside stimuli, beyond human control, borderline shameful and embarrassing, the chemical consequence of extreme emotion, namely anger and outrage. The through line of the show is Banner’s quest to ultimately discover a way to undo the effects of the gamma radiation. (Which raises the disconcerting question: If he no longer possesses such strength, then who will be the one to save him next time?) This was a superhero who was a superhero in spite of himself, changing his skin in order to save his skin. In the aftermath of battle, Banner would invariably wake shoeless, in rags, with no memory of his heroics, all around him evidence of his outsize fury. It’s worth noting that the first thing that is seen during the opening credits of the show is the word anger flashing white on a monitor, which, when the camera pans back reveals it to be the word danger.

And then the program would come to an end, always too soon, with that impossibly slow, sad piano playing as Banner walks down another freeway in another strange city with his backpack on and his thumb out, trying to hitch a ride because he is too poor to own a car — like my mother and I. He was always en route somewhere else, where no one would know him, and where he hoped he would be able to find a cure for his malady so that he could resume living a normal life — while we, the audience, know that he will never find a cure. The message being, I suppose, that beneath our calm, rational life lies a continuous, turbulent other life, a “monstrous” life, one that will always exist, which is as real as our first life, and which we are only barely be aware of — if at all. Herewith the idea of the unconscious.

In what remains to this day a surreal and serendipitous turn of events, not long after I discovered The Incredible Hulk, I was able to meet Bill Bixby. At the time, he happened to be hosting a PBS television program that was being filmed in Pittsburgh, with which my mother, through her job as a secretary at Carnegie-Mellon University, was mildly affiliated. I recall only weeks of anticipation, and then sitting in a studio, filled with cameras and crew, as Bill Bixby tried to recite the opening introduction of the program off a TelePrompTer. He was as handsome in person as he was on television. He was also as good-natured, and he laughed at his frequent stumbles, which prolonged everything. At some point, he was brought a can of Coke by an assistant, a woman whose boys I had sometimes played with. Thanking her for the Coke, he drew her close and pretended to spill a little bit of it onto her high heel, which made her shriek, of course, and I knew that he was flirting with her, and that she was much younger and prettier than my mother.

Finally, he made it through his monologue without error and I was led over to meet him. He was sitting in a chair between takes, and he had makeup on his face, and also what looked like sleep lines on his forehead. I was preoccupied with those sleep lines and wondered if he had them all the time and if they would be visible on television. He shook my hand and asked me what grade I was in and if I’d brought a book for him to sign. The book I’d brought was a library book. I hadn’t known that was what one did when one met a celebrity. Instead, I asked him how he made his eyes turn white. I had always speculated that it must be done by way of lasers.

“Contact lenses,” Bixby said.

And I asked him how he was able to tear his shirt when he flexed his muscles.

“It’s a different actor,” he said. “A bodybuilder.” Which disappointed me.

I had many more questions for him, but the meeting was over; it was time for him to get back to work. It had been so fast and underwhelming. He shook my hand again. He wished me well. He was the type of man one might dream of growing up and becoming.

Saïd Sayrafiezadeh, the recipient of a 2010 Whiting Writers’ Award, is the author of the forthcoming story collection Brief Encounters With the Enemy (out this August) and the memoir When Skateboards Will Be Free.