There are about 1,000 reasons to see director Chen Shi-Zheng’s Monkey: Journey to the West, the gaudy, goofy flagship popera opening this year’s Lincoln Center Festival—but if you go in expecting those reasons to align in perfect concert, you’ll likely find yourself perplexed. For better or worse, Cirque du Soleil and its many imitators have taught us to think of large-scale, visually sumptuous, physically virtuoso entertainments as music videos performed live, nonsensical yet seamless and immersive. But despite some superficial similarities—reams of billowing fabric, furious action, zero body fat, abundant acrobatics and combat-dance, tricky world beats by Blur’s Damon Albarn and production design by Jamie Hewlett (the two of them make up the animated band Gorillaz)—Monkey is a different beast. It’s a motley chimera at once fluid and shambling, with roots in Chinese opera and a narrative metabolism far more jagged than Cirque’s. If its Quebeçois cognate is a luge, this is a decathlon—with some of the exhaustion that image implies.

This journey is decidedly not designed for a frictionless surface. It’s a woolly, windy, winding thing, an episodic Qing Dynasty wisdom quest–adventure tale that’s as familiar to Chinese audiences as The Wizard of Oz is to American ones. Monkey (played by the live-wire Wang Lu the night I attended; he alternates with Cao Yangyang) is a Loki-like, semi-divine trickster (and also an actual monkey, with actual monkey habits and mannerisms) who offends the Pantheon with his irreverence, ambition, and violence. Especially violence—that’s his specialty. Monkey is traditionally a representation of the fantastic, fiendish, enlightenment-resistant human mind, but this broin’-out ape isn’t a particularly deep or creative thinker, and his schemes don’t extend much further than his immediate puerile impulses. Aside from his hyperactive drive for life eternal, he wouldn’t be out of place at a neighborhood sports bar or a basement Apatow marathon. His priorities are: fun, then grandiosity (he declares himself “Great Sage Equal to Heaven,” the same thing Sylvester Stallone had on his business card between 1986 and 1989), then weaponry (a magic pole he extorts from an undersea kingdom in a bubbly, bonkers marine sequence), and, ultimately, immortality.

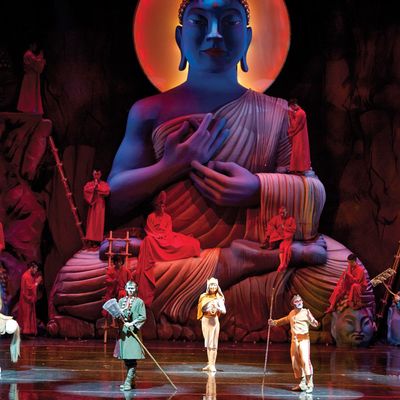

Naturally, he leaves out enlightenment, and hubris catches up. After a brief 500-year imprisonment beneath the great hand of Buddha—one of the show’s most indelible images—the scamp is offered a chance to redeem himself by accompanying a defenseless young monk called Tripitaka (Li Li) west to India, where he will seek out sutras to bring back to scripture-starved China. Along the way, Monkey gets to practice more of the violence he’s renowned for: Every demon in creation wants a bite of Tripitaka. If the Buddhist/Taoist themes, along with narrative details and even key characters, sound like they’re a bit fudged and upstaged by a blizzard of visuals, I assure you, they are. (The same was true of Mary Zimmerman’s far textier 1996 take on this same source material.) Through it all, Monkey never stops moving—physically, at least. His character seems, to these cloudy Western eyes, a little immobile. His interactions with his fellow pilgrims, both human and non—the grossly sensual Pigsy (Xu Kejia/Liu Kun), a man under a porcine curse; the low-key man-eating river demon Sandy (Dong Borui/Li Lianzheng)—are minimized here. There’s far more Monkey than Journey in this journey, and local tastes may vary. Chen has labored to create a less cute, more flawed simian than the puckish sprite of Chinese opera and folklore—and this track-suited bad boy is certainly a rogue, perhaps even a sociopath. But not, in my opinion, a terribly deep one.

Even if you do see Monkey as a glorious multidimensional character—Falstaff with a six-pack—the challenge in engaging with this happy cacophony, where the handsomely mythic and the playfully tacky fidget side by side, comes down to flow. We don’t need to know where we’re going or why—modern life and summer blockbusters have cured us of those ancient cravings—but we do need to feel the motion. Monkey, for better and worse, intentionally and unintentionally, denies Westerners their basic Freytag momentum, even as the directors and designers set up banquet after banquet of splashy cartoon set pieces. Oh yes, and actual cartoons! Hewlett covers set changes with animation, in his trademark super-2D Gorillaz style. But the fit with the theater-art, while occasionally clever, isn’t a vacuum seal—there are a lot of air bubbles in this show. Chen has a team of choreographers coordinating the spectacle, and Monkey feels like the work of a team, not the coalescing of a discrete vision: The canvas spills over with teeming activity, with little overt central planning. Sometimes the effect is powerful, a Bosch mosh pit, full of vitality. But just as often it feels like an ad hoc street fair, where you’re never quite sure where to look or what line to join. And it all seems to be very, very far away, so joining in, if you’re inclined, doesn’t feel even remotely possible. There’s an ocean of mute space between the audience and this show, and that gulf only grows.

By the time my brain realized it wasn’t being whisked along at speed but used as a flotation device, I’d already entered the trance state I generally associate with lava lamps and late-night Adult Swim cartoon binges. It’s not a bad mind space to hang out in—I just kept wishing we could all adjourn to a nice cozy planetarium. If we’re doing immersion instead of headlong hurtling, by all means, immerse me—distance is the enemy here. Problematically, the Koch, bless its big bones, is all distance, and no place to bliss out, Buddhistically or otherwise: You keep feeling like you’ll trip and hurt yourself. Which you absolutely should not do. That’s Monkey’s job.

Monkey: Journey to the West; Lincoln Center Festival, David H. Koch Theater. Through July 28.

*This article originally appears in the July 22, 2013 issue of New York Magazine.