This interview originally ran on May 1, 2014. We are republishing it now in time for this weekend’s Guardians of the Galaxy.

With the possible exception of Stan Lee, no writer has thought about Spider-Man more than Brian Michael Bendis. The 46-year-old Marvel Comics scribe has penned hundreds of issues’ worth of stories about the web-slinger since launching the ongoing series Ultimate Spider-Man in October of 2000. That title just hit 200 issues, each of which was written by Bendis. In the meantime, he’s also featured Spidey in his decade-long run as writer of multiple Avengers series, as well as in several Marvel-wide crossover events.

As you might infer, Bendis’s influence extends far beyond Spider-Man. He currently writes six monthly series, sits on a creative committee that offers consultation to the filmmakers behind the Marvel cinematic universe, and just got back from a company retreat where he helped the company plan the next few years of its future. And in a summer where Spider-Man, the X-Men, and the Guardians of the Galaxy are all headlining tentpole movies, Bendis is writing flagship titles for all three franchises. In short, he is — and has been, for many years — Marvel’s chief ambassador for converting moviegoers into comics readers.

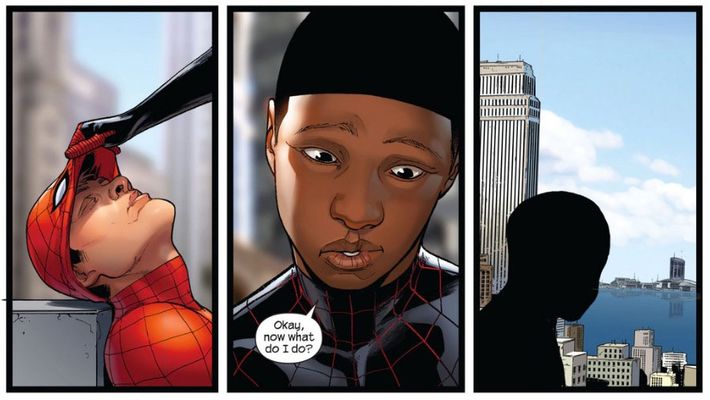

You can trace Bendis’s success to a balancing act he’s mastered: maintaining franchises while also knowing when to take huge risks. In 2011, he killed off Peter Parker in the pages of Ultimate Spider-Man (don’t worry, Peter’s alive and well — Ultimate takes place in an alternate universe) and replaced him with a half-African-American, half-Latino teenager named Miles Morales. Despite some initial uproar (Glenn Beck infamously said the character was part of a Michelle Obama–led conspiracy), Miles has become a fan favorite. In fact, Ultimate Spider-Man is being retitled next Wednesday, May 7, as Miles Morales: Ultimate Spider-Man. Bendis has quietly become a champion of diversity in superhero comics elsewhere, too — filling his ongoing titles with nonwhite, non-male protagonists.

With this summer’s big-screen Marvel movies — as well as a TV show based on his cop-superhero mash-up Powers, which will debut soon as the first original series made for PlayStation consoles — on the near horizon, we caught up with Bendis to talk about how Spider-Man has always been multicultural (despite the statements of the movie’s producers, which were delivered long after our interview), why people should care about an obscure team like the Guardians of the Galaxy, and what it was like to work for Marvel when the company was so bankrupt that it was selling its own filing cabinets.

In your 15-ish years of uninterrupted Spider-Man writing, what have you learned about the concept?

It’s a story with a very strong theme: “With great power comes great responsibility.” And that theme is so perfect in its simplicity that you could build a religion around it. As a fan, I carried it around with me, but when you start writing it, you realize, Oh, this is the most important lesson in the world. It’s not a superpower lesson. It’s a lesson about power, itself. If you have the power to sing, or to grab people’s attention, or anything, then with that comes responsibility that you need to identify and raise yourself up to. I had no children when I started [Ultimate Spider-Man], and now I have four, and it’s what I teach them.

So you’ve had the classic Peter-and–Uncle Ben talk with them?

No, because if you actually say “with great power comes great responsibility” out loud, you get murdered right after. [Laughs.] I do not want an ironic death. I don’t want to have Uncle Ben’s death as the writer of Spider-Man. I can’t handle that.

Let’s turn that previous question on its ear. In your years of writing, have you added something to the Spider-Man concept?

Y’know, my job is very unique. I write Ultimate Spider-Man, which from the get-go was supposed to be starting from scratch, asking what would happen if Spider-Man started today and was not something that started in the 1960s. And the transition that we made was based on the fact that the concept of Spider-Man wasn’t broken. The Spider-Man origin and its themes are pretty much perfect. So adaptations are much like a Shakespeare play: The trick isn’t to fix it and say you know better than Shakespeare. It’s to find the truth of it and keep the truth going for a new audience.

The most cosmetic change we made, obviously, is a couple of years ago when we made the determination that, if Spider-Man were created today, there’s a very large percentage chance that, based on where he’s living and who he is, that he would be a person of color. So we made the choice to send Peter Parker off with a heroic death and have a new young man take the mantle in the form of Miles Morales, who’s half Hispanic and half African-American. That gave a multicultural voice to Spider-Man that was always there, but never fully championed in the books themselves.

What do you mean by that? How was a multicultural aspect “always there” during decades of Spider-Man being white?

When you become the writer of Spider-Man, all of a sudden, every day, every week, every month, someone of color — all different races — comes up to you and tells you, “Spider-Man was my favorite and this is why,” and then I hear a version of this story: “My friends, when I was a kid, wouldn’t let me be Superman, wouldn’t let me be Batman, because of my skin color. But I could always be Spider-Man, and Spider-Man became my favorite. As a little kid, I didn’t even understand why he was my favorite, but it was because anybody could be Spider-Man under that costume, because it was head-to-toe.” That’s not why we created a Spider-Man who’s a person of color, but afterwards, I was like, “Oh man, this was subconsciously why we did it.”

Owing to the bizarre world of licensing disputes, Marvel Entertainment doesn’t have creative control over the Spider-Man movies. But since Sony owns the film rights to the Spider-Man characters, Miles Morales could theoretically become the onscreen Spider-Man. Do you think we’ll ever see that happen?

Hopefully, whoever’s in charge of movie and media rights will realize that they’re sitting on a goldmine and that they should pursue it as quickly as possible. I can’t imagine why they wouldn’t. We made Miles because we wanted to make Miles, but once you make Miles, you realize it was kind of an obligation to make Miles. Y’know? It was the right thing to do.

Marvel’s comics output has suddenly become very inclusive of nonwhite, non-male characters in the past five or six years. Was there a conscious effort to make that happen? Some big meeting where the editors said it was time to pay attention to inclusivity?

There was no big meeting. It’s a few things. I know I sound like I’m a hundred years old when I say this, but with the growth of the online comics community came more awareness of the world and who’s really reading these books. And y’know what? Sure, there are people who look like Captain America who read comics, but there are very few people in the world who look like Captain America. I go to conventions, and you meet hundreds of people over the course of the day, and no two of them look alike. You see women and people of color who love comics, and there’s nothing representing them in a way that isn’t sexualized or something.

Now, you can’t make these decisions [to be more inclusive] consciously, because then you’re just writing in reaction to things, and that doesn’t work out, dramatically. But subconsciously, if you look at the world around you and see your readers, you go, I wanna write something that I know is true. So you start writing women better and you write people outside of your experience better, because you look at pages of other people’s comics and you don’t recognize it as the world around you.

You attempt to rectify that — sometimes subtly, sometimes boldly — and if enough people are doing that, there’s a sea change. And then you go to the publisher and say, “Miles is gonna be half Hispanic and half African-American,” and they go, “Oh, good, we should publish more of that.” And it’s not just me: It’s [fellow Marvel writers] Matt Fraction and Kelly Sue DeConnick and Ed Brubaker and others who fight the good fight and put characters out there that don’t represent everyone, but all of them put together represent more of the world that we live in. And the response you get back is something else, boy oh boy.

Can you give me an example of that kind of response?

Sure. I don’t make a lot of appearances anymore, but I took my kids to a comics convention recently and this little African-American boy came up to me in his homemade Miles Morales Spider-Man costume, which are not available to purchase. You have to make them yourself. It was just about the cutest thing I’d ever seen in my life.

And, of course, there’s been an insane outpouring of fan support for Captain Marvel and Ms. Marvel, which both star female superheroes — and a lot of that response came before the books were even finished.

Yes! Because that fandom was there, patiently waiting for just that! Saying, “Please show us something like that,” and once it’s there, they throw their hands in the air and rush to buy it. They were always there. They were always there! Waiting for just this thing that’s fun, exciting, and representative.

Speaking of changes, you’ve been at Marvel during a period of insane transformation. When you started, Marvel was grappling with Chapter 11 bankruptcy—

This is absolutely true. It’s so the opposite now, that people don’t even know. When I got hired, I literally thought I was going to be writing one of the last, if not the last, Marvel comics.

You didn’t really think that, did you?

They were full-on in bankruptcy! My first visit to the Marvel bullpen was haunting, because they were literally selling filing cabinets.

Come on.

Dude. There was a big pile of filing cabinets back in the corner. I was like, “What’s that?” and someone said, “Oh, they’re selling them.” You’re a fan from a long time ago, right? Stan Lee sold the idea of the bullpen as being this crazy circus, and then I got there, and in the middle section of the bullpen, the lights are out and the computers are gone. There was a small row of editors there, and that’s the only place where the lights were on. So I remember saying to myself, I guess this is the end!

But they quickly turned it around by making some very good decisions, one of which was launching Ultimate Spider-Man and using that as leverage for a lot of mainstream attention and licensing. Then, quickly, the Spider-Man movie was a big component of Marvel righting itself. Riding that wave all the way through the Iron Man movie and the Avengers movie. It’s been an amazing change of course. I saw it at its absolute lowest, and now it’s one of the crown jewels.

With that enormous success of the Marvel movies, has there been a new pressure to make the comics sync up with the films? For example, you relaunched Guardians of the Galaxy as a comic just a year or so before the movie debuted. Is there a philosophy of, “These comics have to tie in to the movie somehow”?

No, actually, and that’s why I like it. If you’re seeing the movie, you don’t wanna come read the comic book and have the same experience. You want someone to go, “If you like the movie, you should see what they’re doing in the comic!” You want it to be the advanced course, or the next step. I’ve now done a bunch of franchises as they’ve been put through as movies, and I never got anything but that same note. Hopefully, it’s intriguing enough to moviegoers that they get sucked into the weekly comic-buying habits that you and I have, and which has ruined our lives. [Laughs.]

Also, I think Marvel likes that the Winter Soldier was created in a forward-thinking manner inside the books, and then it was there for them when they were thinking, “What’s the most kick-ass thing we could do with Captain America in the movies?” And it was obviously Winter Soldier! The writers don’t do that stuff with the thought of, “I want this to be in a movie.” But there’s certainly an editorial idea now that they can pluck good ideas from the comics for the movie franchises.

The great comics writer Grant Morrison once said every worthwhile superhero team should be able to be boiled down to a specific social analogue: the Fantastic Four are a family, the X-Men are a school, the Justice League are the United Nations, and so on. By that rubric, what are the Guardians of the Galaxy?

I say they’re pirates for good. But I also think there’s something — a lot of people today end up making their own family. Y’know? There’s the family you came from, and it may have been broken, or you may not have fit in it, or whatever. Then, you grow up and you make your own family. Your friends become more than just friends. The Guardians are like that. The thing that ties them together is, everything that was broken in their lives led to them meeting. They’re banded together by the idea that the world can be a lot better than it is, and we should do something about it immediately. You look at someone like [Guardians of the Galaxy protagonists] Gamora or Peter Quill, and the thing that binds them together is that their fathers really are nightmares, and they do everything they can to correct the damage that their fathers have done to the galaxy.

So it’s “space pirates for good with major daddy issues.”

Right! And nothing says “Marvel” quite like daddy issues.

Along those lines, what’s the core idea of the Avengers? I’ve always found it to be such an amorphous concept.

The essence is getting together to fight the fight they can’t fight by themselves. There’s a power to that idea. The idea of turning to your friends and saying, “I need this. We need to help each other with this.”

Do you think the wild success of the Avengers movie franchise has changed how writers approach Avengers comics?

I think there are certain actors who have embodied certain characters so perfectly that, if readers don’t see a semblance of that in the comics version of that character, they won’t see it as correct. Robert Downey Jr. is, of course, the pinnacle of this. But I think the first time it happened was with Patrick Stewart as Professor X. It could be that some people heard a voice similar to his as Professor X, but now I think it’s all they hear. And now, if you write it as not sounding like that voice, people will just see it as wrong.

Do you see fans of superhero movies become readers of superhero comics?

Oh, for sure. Y’know, there’s a frustration sometimes, where people say, “Why don’t all people who watch The Avengers start reading comics?” And I’m more like, “Why don’t all people who watch The Avengers read at all?” [Laughs.] It’s more of a problem with people not reading, in general.

The next step of what we’re really talking about, which will be very interesting, is if comics start to take over television. I actually always thought that was a more logical transition, because comics are an ongoing pile of cliff-hangers in serialized stories. I must say, it took a lot longer than I thought it was going to. I thought it’d happen ten years ago. But now, we’re on the cusp: We’ve got the Netflix Marvel shows, the Powers television show is coming, Arrow, all these other things. That pure serialized storytelling and the quiet character moments that comics do so well — that’ll fully bloom on the small screen, and that’ll be a game-changer.

What’s the superhero comics industry’s biggest challenge?

Oh, I got a pile of stuff. Just yesterday, a woman wrote an article analyzing what she thought was a poor comic book cover, and she was met with just a bunch of shitty anonymous people being awful to her online. I think that a huge problem is people who read comics and don’t understand the point of superheroes, which is to be the best version of yourself. You love Captain America? Well, you know what Captain America would never do? Go online anonymously and shit on a girl for having an opinion.

I would like there to be more of a connection between why people read these stories, and how they act. You should see Peter Parker and then want to act like Peter Parker. You shouldn’t want to be Peter Parker because you want to sling webs and punch people. It should be because you want to be someone who lives with the idea of “with great power comes great responsibility.” And that means that the power of the internet and the power of your ability to interact with people, should be treated like a power. You should treat it like a responsibility.

Wow, look at you, you really brought that full circle!

Yeah, you see what I did there? [Laughs.]