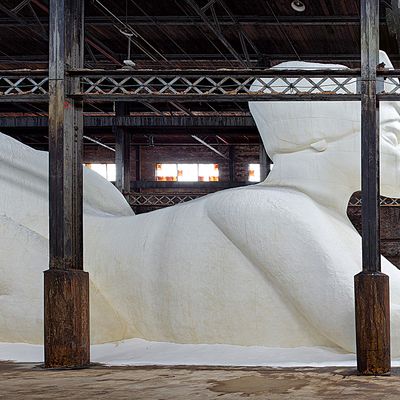

Midway through my maiden visit to the derelict Domino Sugar refinery near the Williamsburg Bridge, while gaping in awe at Kara Walker’s great gaudy monstrosity, her towering naked sphinx with the head scarf and features of a black mammy, I had something like a vision. That’s the crazy comical power Walker’s best work can have. Particularly this work, elliptically and archaically titled A Subtlety: Or the Marvelous Sugar Baby, an Homage to the unpaid and overworked Artisans who have refined our Sweet tastes from the cane fields to the Kitchens of the New World on the Occasion of the demolition of the Domino Sugar Refining Plant. This behemoth, part Cecil B. DeMille parade float, part alien, is accompanied by a retinue of life-size deformed black figures, boys carrying bananas or baskets with parts of other boys, all made from molasses and brown sugar.

I imagined this mad theatrical 35-ton thing—more than 35 feet high and 75 feet long, fashioned in refined white sugar over blocks of Styrofoam—pulled across the United States by the crew of misshapen brown attendants. I saw its ambiguous anarchic meanings, its otherness, stunning all who saw it. I fancied this an American ghost ship, never coming to rest until … what? I don’t know. I saw a new American Pequod, some Melvillian symbol for the original sin of slavery and its disquieting contemporary connections to the kind of hubris that brought us Iraq and then Abu Ghraib. Things that make America lose its humanity. Walker, who called A Subtlety “a New World sphinx,” has said that her work “is about trying to get a grasp on history … it’s kind of a trap … the meaty, unresolved, mucky blood lust of talking about race where I always feel like the conversation is inconclusive.”

That trap looms in this incredible sculpture, impeccably presented in the decrepit Domino refinery by Creative Time. This dank building, where layers of history are caked on the walls with molasses, this place where brown sugar was turned white, multiplies the lurking meanings in Walker’s work. Especially as no one captures and portrays the implicit connections between sex and power like this gifted artist. Sex is simultaneously visible and implied in her work, the abject violations of slavery and its long aftermath always close to the surface. (Her other art runs amok with mammies, pickaninnies, and Sambos being raped, beaten, or wooed by slave masters and southern belles.) Whiffs of Goya’s depictions of evil come to mind.

Walker has been an artistic force since 1992, when she first got the idea of using the so-called “minor art” of paper silhouettes to render—in vast, wall-filling panoramas—horrific, violent, and sexualized scenes of the antebellum South. I first saw her work while she was still a RISD student and hadn’t yet hit on this device, one that reduces the world to monochrome and that, she once said, “kind of saved me.” Still, I gleaned, in a large drawing of black girls, done in chocolate, what I perceived as a new barbaric yawp come into America. Since then, and after receiving a MacArthur Award in 1997 at the age of 27, Walker has only gotten better, more wicked and out-there.

A Subtlety depicts a black-featured woman with enormous hindquarters arched and exposed, her protruding vulva presented as if for sexual delectation. She crouches, her breasts visible, her left thumb thrust through split fingers in an ancient visceral symbol for sex called the fig. Walker has never worked in three dimensions like this. Maybe no one has. This massive sculptural juggernaut—all this white in the midst of this dead factory coated in congealed brown sugar—suggests hidden causes and effects, cosmic condemnations, menace, cruel pleasures, and inscrutable things. I imagined birds of prey circling over it. Vitriol, fatalism, and grandiosity merge. James Baldwin once wrote of the white American remembering slavery as “a kind of Eden in which he loved black people and they loved him … everything … is permitted him except the love he remembers and has never ceased to need.” Baldwin suggests that this is partly the malignant cause of the “hysteria” of racism. As Walker puts it more concisely, “This sugar has blood on its hands.”

As I considered this while pondering A Subtlety, allusions to the Pequod gave way. Something darker, universal, and more unknowable formed. The white sculpture morphs in the mind into a stand-in for Melville’s white whale itself. The psychic bottom falls out. I remembered D. H. Lawrence’s incredible analysis of Moby-Dick: “Doom! Doom! Doom! Something seems to whisper it in the very dark trees of America. Doom! … Doom of our white day … And the doom is in America. The doom of our white day.” Then my vision came to an end.

A Subtlety: Or the Marvelous Sugar Baby, an Homage to the unpaid and overworked Artisans who have refined our Sweet tastes from the cane fields to the Kitchens of the New World on the Occasion of the demolition of the Domino Sugar Refining Plant. Kara Walker. Domino Sugar Refinery, Williamsburg.

*This article appears in the June 2, 2014 issue of New York Magazine.