Celebrity architects are in bad odor these days. The roll call of brand-name globe-trotters is full of aging icons (Koolhaas, Gehry, Hadid, Foster, Calatrava, Safdie, Nouvel, etc.) who have committed acts of unspeakable grandiosity. Their immense white waves and shiny curves, their jaunty walls and teetering cantilevers remain popular with despots and overweening developers, but they have given many critics a hangover. Some feel our time demands a gentler architecture, more demure, self-effacing, and off the shelf: an architecture Garrison Keillor could love. Yet during a recent jaunt through Keillor country I made a pilgrimage to a series of idiosyncratic extravaganzas that remain astounding more than 50 years after the death of their creator, Frank Lloyd Wright. Fallingwater in western Pennsylvania, Taliesin in Spring Green, Wisconsin, the SC Johnson headquarters in Racine, the First Unitarian Society of Madison’s meeting house—this processional of midwestern masterpieces reminds us that great architecture is not always the most sensible solution, or the most frugal, or the sturdiest. Sometimes it’s brilliantly insane.

Famous architects can be obsessive, finicky, egotistical, and impractical. Wright was more obsessive, finicky, egotistical, and impractical. His buildings leaked and deteriorated so precipitously that restoration sometimes borders on reconstruction. His bathrooms are cramped, his ceilings low, his kitchens afterthoughts, his staircases so narrow that one has to go on a diet to climb one. These faults are the product not of sloppy thinking but of profound if perverse desire.

Taliesin expresses a powerful faith in domestic tranquillity. Nestled into a fluorescent-green fold in the Wisconsin countryside, it was a place where Wright could retreat, regroup, and gather his thoughts and his minions. It’s also a place that burned down twice, where Wright holed up after abandoning his wife and children, and where his mistress and her kids were hacked to death by an employee. Wright returned, remarried, and rebuilt, obsessively tinkering and expanding until the end of his life—and beyond. Like Fallingwater, Taliesin has required constant tending. On the day I visited, workers had just removed a plastic sheet that blocked the view from Wright’s bedroom for nearly three years, while the loggia’s flagstones were numbered, torn up, and reinstalled. Today, the home is a monument to itself and to the flawed, ornery genius who made it. Wandering from room to room, stroking the rough walls, savoring the play of ocher walls, Cherokee-red trim, and spring-green-tinted sunlight on shiny stone floors—all that sensual contact with the building makes practical objections seem beside the point. Nothing could be more sublimely pointless than the beautiful “bird walk,” a narrow cantilever jutting precipitously from one wall, like a springboard into the landscape. This rural shrine exerts a Druidic power.

Few living architects express themselves so fully and so harmoniously at the tiniest and largest scales. His archive, which recently landed at Columbia and the Museum of Modern Art, includes grandiloquent visions of ultratall skyscraper, highways, and pastoral utopias. At the same time, Wright made buildings that people want to touch; he deployed color, stitched tiny details into a grand conception, and offset grandeur with intimacy. The way a glass pane meets another at a corner, without a frame to hold them together; the way a window disappears into a stone wall or appears unexpectedly under an eave to catch an afternoon slant of sun; the way a long hallway drives through dimness to a gleaming view beyond, or a canopy dips down as if the house were reaching out to welcome a visitor inside; the way shadow and brilliance dance, and a banquette affords a pleasing panorama of a whole room—Wright could manage all these interactions of light and solid mass the way a composer handles counterpoint. We should not worship these works into a state of dusty innocuousness. They remain as radical as Beethoven symphonies, and as with those musical monuments, their radicalism has become hard to see.

Today, the biggest architects flaunt extremes of style and engineering, work on a colossal scale, and know how to awe and intimidate people but not how to soothe and embrace them. Wright’s spaces can be intimate to the point of claustrophobia—a six-foot-four man on my tour of Taliesin had to duck for low ceilings, and his head disappeared into raised ones. But, with rare exceptions (the abysmal white elephant of the Monona Terrace convention center in Madison), Wright never crushed a human soul in a huge and heavy void. You don’t feel small in a building by Frank Lloyd Wright.

In Wright’s world, behavior must adapt to a powerful artistic idea, rather than the other way around. Clients had to earn the architecture they occupied. That intransigence did not endear him to corporate America, but somehow he meshed well with SC Johnson, the Racine-based company that makes tile cleansers, floor wax, and furniture polish. The company’s chief, H. F. Johnson Jr., wanted the world’s best office building, even if that meant submitting to an imperious architect.

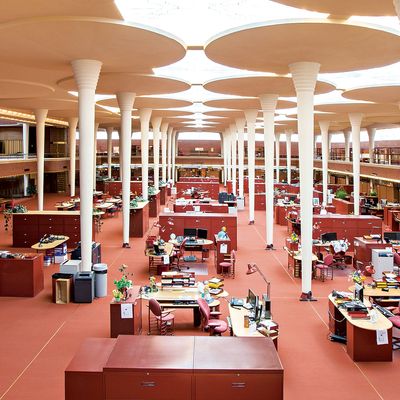

What he got was a stunning combination of the rustic and the modern. The administration building, a spacious managerial glade in a forest of sculpted pillars that spread like chestnut trees, opened in 1939. The Research Tower, which opened in 1950, stands like an air-traffic-control center over the low-lying landscape, calling attention to the dogged pursuit of a clean, shiny, and fresh-smelling future. At the same time, the complex, clad mostly in plain and simple brick, resonates with the Wisconsin countryside, which is dotted with similar combinations of low barn and cylindrical silo. The tower, balancing like an upright block on a lifted finger, is coy about the activities it contains. Translucent bands suggest plenty but reveal only the alternating rhythm of square slabs and circular mezzanines. Wright screened off the outside world by constructing windows out of stacked glass tubes, a nod both to the lab and the log cabin. The tubes leaked and fogged, until eventually the company replaced them with Pyrex and a sturdier silicone sealant developed by Dow Corning. It’s amazing how quickly advanced technology can become primitive.

By linking the administration and research buildings, Wright challenged the Great Depression with his optimism, creating a habitat for invention, paperwork, and good design that promised a happy, dustless world. But the scientists who worked in the tower begged for shade and sprinklers and air conditioning and ample elevators. Wright refused them all. He bathed the work areas in dazzling white brightness, and insisted that a fireproof building would never burn, that sprinklers were unsightly and unnecessary. A bigger elevator core would throw off the tower’s proportions. So the scientists took the stairs, sweated and squinted (and rebelliously hung curtains). Eventually, they moved out. The tower lay fallow until a few months ago, when the company opened two of the restored floors for guided tours.

Too often, the pursuit of great architecture has become an excuse for preposterously self-indulgent design, much of it built with public money. Peter Eisenman’s gargantuan City of Culture comes to mind, crouching on a hill outside Santiago de Compostela, a cold, coiled, and perpetually unfinished compendium of arcane architectural theories. Wright’s example is a corrective. He was the rare architect who felt landscape in his bones and whose buildings improve on nature, who felt no hesitation about dominating a site, but insisted on understanding it first. His greatest buildings still stand not because they earn their keep but because they make the most effective and least quantifiable claim to endurance: sheer, immoderate adoration.

*This article appears in the August 11, 2014 issue of New York Magazine.