The older the money, the stingier the meal — or so goes a persistent Wasp stereotype. Onstage, too, the rich can be unforthcoming. A.R. Gurney’s Love Letters, an epistolary play about such withholding among the upper crust, also suffers from it, partly the result of its stuntlike conception. It tells the story of stuffy but successful Andrew Makepeace Ladd III and free-spirited but doomed Melissa Gardner from the time they first encounter each other in second grade to about the age of 55, a period roughly coinciding with Earth years 1940 through 1988, when the play was first produced.

I say “story,” but of necessity Love Letters is more of a précis, dropping in on representative moments in the two characters’ lives not only through the proper letters they write but via valentines, picture postcards, RSVPs, Halloween cards, thank-you notes, condolence notes, and notes passed in class. Despite the variety of mail, this is a limited palette. For most of the show’s 90 minutes they do not even share a glance, let alone anything that passes for dialogue; there is no set but a table that cuts off their bottom halves and chairs from which they never rise. This dramaturgy, evidently meant to scrape away all distraction and focus our attention on the purity of actors reading (they have scripts on little lecterns), mostly succeeds in proving that “starve a cold, feed a fever” doesn’t apply to the theater. Starve a play and you don’t have a play. You have what even Gurney, in an introduction to the printed script, calls a “sort of” play, an “event.”

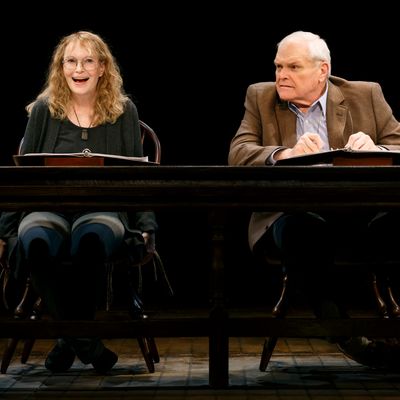

So let’s look at Love Letters as an event — a job made easier by the stunt the producers of the revival have come up with to match the playwright’s. At the moment, Mia Farrow and Brian Dennehy star, but the cast will switch every month or so, with Carol Burnett, Candice Bergen, Diana Rigg, and Anjelica Huston among the upcoming Melissas, and Alan Alda, Stacy Keach, and Martin Sheen among the Andys. You can see the appeal of the material to this demographic of actors, who range in age from 63 to 81: a short gig, no memorization, and — here’s the trick — juicy roles. For Love Letters is a kind of reverse Potemkin village: a false structure with real people in it.

Or at any rate real enough when an actress like Farrow gets her teeth on its flesh. Though Gurney explicitly requests no baby talk or mugging, Farrow, under the delicate direction of Gregory Mosher, pushes that line, always to good effect, especially in the early scenes representing Melissa’s awkward childhood and adolescence. She builds her performance daringly from a base of whimsy and entitlement through adolescent petulance and rebellion (Melissa gets kicked out of boarding school for sneaking a drink) through the wildness of an unmoored young adulthood to fortysomething desperation and, eventually, mental illness. Andy’s trajectory is less dramatic. He’s one of those boys already stiffened at 10 by the burden of expectations, both as a constraint (we don’t do such things) and as a responsibility (we must do such things). As he matures, he boxes himself further into the trappings of that upper class cell as he trudges through prep school and Yale and law school all the way to the U.S. Senate without ever busting a button. It is only in his letter-writing that he reveals his “truer” self: a man who is as romantic where it doesn’t count, on paper, as Melissa is where it’s most dangerous — in life.

Dennehy more than Farrow seems constrained by those damned chairs; he’s a physical performer with half his range out-of-commission. As a result, he does a lot of acting with his teeth. Still, he provides the solid backboard against which Farrow can fling herself like a tennis ball; when she breaks through, momentarily, in the second half, it’s a joy. And when she is subsequently abandoned by Andy, who cannot afford the publicity of a crazy mistress just as his Senate reelection campaign is heating up, her rage and pain are harrowing to behold. The deeper imagination that made her so appealing to Andy has led her astray, abetted by a pesky alcoholism gene.

This insight, like much in the architecture of the characters, is provocative; Gurney knows the territory well enough to act as a guide to its most dangerous corners. Also its most annoying and absurd ones. He gets the insufferable tone of the Wasp holiday letter just right: “Let’s start at the top, with our quarterback, Jane herself, who never ceases to amaze us all,” Andy writes of his wife. He catches, too, the subtle delineations of class within class: The rich, like Andy, have affairs; the richer, like Melissa, have divorces. And he demonstrates how racism and anti-Semitism are secondary elaborations of simple snobbery: “No one sends Easter cards except maids,” Melissa writes in an Easter card.

But Gurney’s sharpest criticism is reserved not for his characters — they have to be forgiven everything, or the play would just halt — but rather for the totalitarianism of the parents and institutions who raised them, shoving boys and girls toward each other, and then just as ruthlessly segregating them in finishing schools and all-male enclaves from Hotchkiss to the Senate. “I’ve thought about all those dumb things which were done to us when we were young,” Andy writes. “We had absent parents, slapping nurses, stupid rules, obsolete schooling, empty rituals, hopelessly confusing sexual customs … oh my God, when I think about it now, it’s almost unbelievable, it’s a fantasy, it’s like back in the Oz books, the way we grew up.” And this is coming from the character who had the happier upbringing, being a boy. Gurney is able to suggest — but it takes Farrow’s brilliance to really flesh out — the ways some women born into the wife-making machine of the mid-century aristocracy were absolutely mangled by it. Melissa’s casual mention of a stepfather “bothering me in bed, if you must know,” as if it were an ordinary annoyance of being a girl at that time, is horrifying in its understatement — though of course, coming out of the mouth of Mia Farrow, it’s also strangely complicated.

Gurney has an overfondness for structural tricks; another is currently on view in The Wayside Motor Inn at the Signature. But in Love Letters, at least, the artificial restriction brought out something compensatory in him, especially when the letters are allowed to escape their strict my-turn-your-turn alternation. Most moving are the holes, the lacunae left by one character’s refusal, in a snit or in trouble, to reply, or to accept the feeble cajolery of the other, sometimes for years. The result, tellingly, is a spongiform record of a relationship. Are not all relationships as much empty space as connective tissue? But the pitfalls of the play’s structure are just as evident, and Gurney steps right into them. How, for instance, do you end such a correspondence? Gurney does it, unfortunately, with an explicitly heart-tugging coda that breaks the frame — too little, too late. In a play (or even just an event) clearly meant to be a love letter to writing letters, he settles for a most uncomplimentary close.

Love Letters is at the Brooks Atkinson Theatre.