Rivers Cuomo is not kidding when he raps. “I’m just trying to make something I think is amazing,” the Weezer front man says of his efforts in oft-misunderstood efforts like “Can’t Stop Partying” and “The Greatest Man That Ever Lived.” “When people are shocked or offended, I’m surprised — because I think it’s great. From the day we put out Pinkerton, this is my fate. It turns out that, as an artist, I have a genuine passion for things that can ruffle the feathers of the audience.”

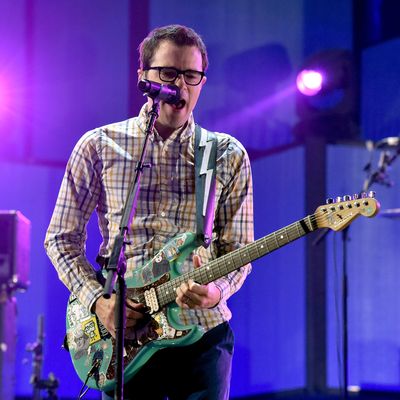

These days, every new Weezer album is compared to the band’s two ‘90s classics, their self-titled debut (a.k.a. the Blue Album) and Pinkerton. But their latest effort, Everything Will Be Alright in the End, which hews more closely to the pop-rock sound that made them famous, has been met mostly with praise (Vulture’s Lindsay Zoladz is among the exceptions). Cuomo took a few moments to discuss Weezer’s past and present as the band prepared to play the new record in its entirety on tour.

Do you ever wish you could release a new album unencumbered by the burden of your earlier work?

I think most fans now are treating this record as its own thing. It’s beautiful and amazing, and there’s no point in comparing it to any other record. That’s certainly the way we felt when we were making it — and I think people who are caught up in comparing one album to another probably aren’t in the core community we care about.

Why are you so fond of the Weezer Cruise?

It’s a surprising feeling of love from all the fans. Normally we see feedback online, which can feel a lot harsher. You don’t realize how much people care about you until you’re face-to-face with them; they just want what’s best for us. It’s such a treat to be on a boat with a few thousand people who love Weezer as much as we do, with no one picking on you.

Still, as someone who’s struggled with fame — a segment of your album is called “The Panopticon Artist” — is there something strange about being on a boat surrounded by people who are really into your band and have paid to be there?

No! It’s a good question. If I could live there all the time, would I? Maybe I would. It’s kind of idyllic [Laughs.]

What was a particularly dark moment of online feedback?

I’m just remembering the very first time I experienced a reaction online. That was in the comments on Amazon.com in 1996, when Pinkerton came out. It was brutal. People were just so disgusted by the lyrics. I remember my mom was showing [the comments] to me, and it was extra painful to know that she was seeing these really awful things people were saying about me.

Is there one specific insult you remember?

The one line that sticks in my mind is actually from two years before that — but it wasn’t on the internet. It was from a weekly paper, a local paper wherever we were on tour. It was a reference to the Blue Album. There were one-sentence reviews. It may not even make sense to a younger generation, but at the time it was quite an insult: They called us “Stone Temple Pixies.” When Stone Temple Pilots — who have a lot more respect now — first came out in the early ‘90s, they were the critics’ whipping boy for sounding like every other grunge band, like every song on their album was an exact copy of some other grunge band before them. Basically, this critic was saying we were the “Stone Temple” version of the Pixies.

On the new album, it seems like you took a lot of time with the arrangements. How did you decide to whistle the hook on “Da Vinci”?

We all thought it was a great song, but it needed some kind of sonic element to make it pop. Scott [Shriner, the bassist] suggested we put in a synth line with the guitar in the beginning, and he demonstrated his suggestion by whistling it. I thought the sound of him whistling was incredibly cool — way cooler than any synth we could put on there. So I suggested we all go in and whistle.

In “Back to the Shack,” you sing: “disco sucks.” Disco is hardly today’s dominant pop genre. Where were you coming from with that line?

Well, it’s supposed to be in quotation marks. And I think it is on the digital booklet, but for some reason it got left out of the first printing of the CD booklet. Maybe this is a generational thing again, but that was a popular slogan at the end of the disco area. I don’t know … it’s in quotation marks because it’s not necessarily true for me. The speaker in that song is a little shifty, I’ve got to admit.

Early on, you wrote a lot of vivid songs about girls that teenage fans could relate to. How did your relationship with women change after you became famous?

I think I documented the change pretty clearly on Pinkerton. I didn’t get as much attention as I wanted from girls as a teenager. I thought that if I became a rock star, I would finally get all that I wanted — but it didn’t happen. We had great success, but for some reason it didn’t feel like I was in Mötley Crüe. Maybe it was because our fans at the time were 10 years old, or maybe it was because that generation of girls didn’t want that kind of relationship with their favorite musicians. They looked at me as a nice boy who was really pure-minded. I didn’t want to be trapped in that image — so I wrote a very tell-all set of lyrics on Pinkerton, which I hoped would expose the real me. I know it would probably scare off a lot of women, but the ones that remained would be interested in the same thing as me.

So Pinkerton was partially a message to women?

[Laughs.] I think we could probably say that about a majority of rock albums.

When you recorded the State Farm Insurance song — which was originally written by Barry Manilow — it got strong reactions. Paradoxically, part of that may have stemmed from how good it sounded. It was such an emotional interpretation of an insurance-company jingle. Did you have any hesitation about taking on that project?

No hesitation at all. I’m a huge Barry Manilow fan, and I’m a huge fan of that melody. I found out that he wrote it, and it was this forgotten song that existed as a full song. When I heard it, I was so excited because I knew that I would be able to sing it well and Weezer would be able to play it well. I just love it.

When your first album came out, your image was an important part of how your audience connected with you. Did you see yourselves as nerdy, or were you surprised by how the world saw you?

We were totally surprised. Before our record came out, in the two years we were playing in clubs finding our voice, we never once used the words geek or nerd. We never thought of ourselves that way. All the cool kids in L.A. that we knew looked like us. They had glasses and short hair and kind of looked like anti-rock-stars. It wasn’t until the record came out and we came into contact with Middle America that we realized everyone thought we were geeks and nerds. We thought we were the next Nirvana.