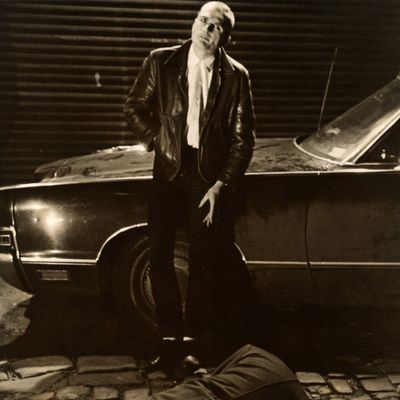

In a 1995 interview, director Kathryn Bigelow (of Zero Dark Thirty and The Hurt Locker fame) recalled filming The Set-Up — her experimental short film that she ended up submitting as her MFA thesis with Columbia University. It also happened to be her first cinematic endeavor. “I started shooting at about 9pm and finished at 7am,” she said. “It was in an alley off White Street downtown, and it started to snow.”

In it, two men pummeled each other to a bloody pulp, accompanied by a voice-over of two philosophy professors providing dry commentary. “I knew exactly what I wanted,” said Bigelow. “But I didn’t understand that you fake shots and fake hits and put sound effects in.” As a result, “these guys were getting bloodier and bloodier. They were in bed for two weeks after, I almost killed them.” With French structuralist theory among its influences, The Set-Up took a formal look at violence’s allure and its political connection to fascism; though Bigelow was still in grad school, she’d already refined her aesthetic and conceptual-art chops, having studied as a painter, gone to Whitney’s Independent Study Program, and worked with the likes of Richard Serra and Lawrence Weiner.

Maybe because the Academy Award–winning director downplays this student film — which is also maybe why it’s nowhere to be found online — The Set-Up enjoys a somewhat mythical status in the eyes of cinephiles hoping to trace the director’s skillful deployment of violence back to its very earliest roots. (Critic Dan Kois even issued an online plea asking her to release the film: “We want to see it so bad,” he wrote.) It doesn’t help that the director is notoriously press-shy, turning down profiles from major magazines.

Now, at MoMA this evening, Bigelow’s fans can view The Set-Up alongside the six other short films with which it was screened in 1978. The occasion: an evening restaging of a cinema series organized by Bigelow and filmmaker Michael Oblowitz, who — as twenty-something denizens of New York’s underground cultural scene — were active in a group of grad students and professors who’d founded Semiotext(e), a radical New York–based journal that imported French theory to the U.S. and sought to dissolve boundaries between high and low culture. In 1975, the group staged a conference and a special issue of the magazine, which they called “Schizo-Culture.” Uniting artists, writers, and No Wave bands, the event brought everyone from John Cage to William S. Burroughs into the mix.

Oblowitz remembers meeting Bigelow on their first day as students at Columbia University: “We were the only two students wearing black jeans, motorcycle boots, and leather jackets.” Collaborators henceforth, the two dubbed their film series Cine-Virus — a name inspired by Burroughs, who at the time was comparing words and images to viruses that mutated and infected people’s minds. Partially re-created tonight at MoMA in celebration of Semiotext(e)’s 40th anniversary (which also inspired an afternoon of performances and readings yesterday at P.S. 1), the two-hour-long program includes non-narrative flicks and experimental mash-ups, and ranges from a montage-driven music video for Devo’s first single “Mongoloid” to video “cut-ups” on which William S. Burroughs himself collaborated.

It’s pretty clear that, back then, reaching audiences nationwide wasn’t first and foremost on anyone’s mind (even while Bigelow has said she was discovering that movies were more accessible than painting, her first chosen art form). “Cine-Virus was an epistemological break with syntax,” Oblowitz said. But even as some of those featured in the film series graduated to much higher-profile projects, the evening’s after effects seem to live on in their creative lives. Oblowitz himself later became one of MTV’s first directors and three years ago filmed The Traveler, a horror movie starring Val Kilmer. Though he’d learned to reach a large audience, he said: “I always have symbols, allusions, deconstructions, alienations that harken back to what was first floating through my mind in 1977 and 1978.”

“The legacy of Cine-Virus has not totally surprised me,” Oblowitz added. “It is a virus, after all.”