There are two ways to read Mind MGMT, the critically beloved, psychedelic comics series that Matt Kindt writes and illustrates. You can simply zip through his taut, thrill-filled, globe-trotting plot about ex-spies with bizarre mental abilities. Or you can dig a little deeper and start to drive yourself insane. Kindt’s fine with either strategy, though the second one will give you a better sense of what goes on in Kindt’s own brain.

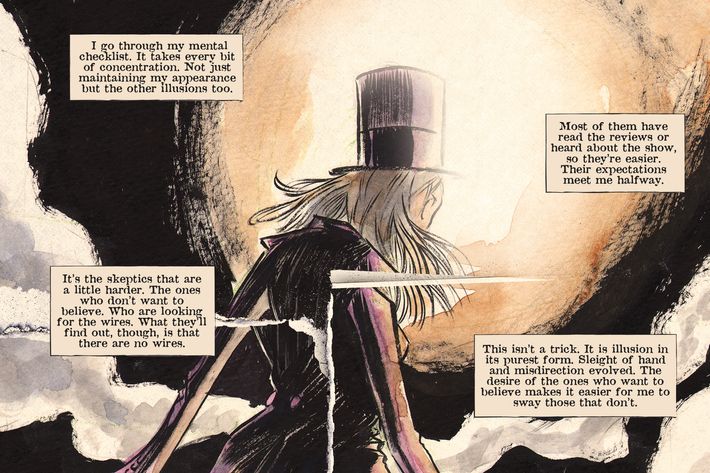

Mind MGMT is filled with back matter, marginalia, and textual clues that have kept obsessive readers coming back to Kindt’s cult-hit comic every month. Its fourth collected edition, The Magician, just hit stands— but it’s far from the only work of his that you can find on a bookshelf. From his home in the suburbs of St. Louis, the 41-year-old creator has cranked out acclaimed work for Marvel, DC, Valiant, and Dark Horse, which publishes Mind MGMT.

For more than a decade, he’s alternated between superhero gigs and tenderly crafted works of his own, such as the radio-influenced noir of Pistolwhip and the spy thriller 2 Sisters. Now, after years of struggle, he’s becoming one of comics’ hottest auteurs. The series has been showered with praise from inside and outside the mainstream comics community (Junot Díaz is an outspoken fan), and 20th Century Fox recently picked up the rights to Mind MGMT (Ridley Scott is rumored to be attached to the project). I sat down with the soft-spoken and charming Kindt at a very loud midtown coffee shop, where we talked about the monks, the Kennedy assassination, and reading hard-core pornography.

Right away, in the first few pages of the first issue of Mind MGMT, there’s a spooky, doomed plane called Flight 815. This was, of course, the famous number of the doomed plane on Lost. Why on earth would you start such a unique series with such an obvious reference?

It was so random. Like, I was writing the script and I’m like, Oh, I should have a flight number here. And I think Lost had just finished and I was like, Oh, Flight 815! That’ll be a funny little inside joke! I didn’t think anybody would get it, honestly.

Come on. You didn’t think anyone would get a Lost reference?

[Laughs.] At that time I was like, By the time it comes out and Lost is over and everyone’s pissed at the ending, no one will care. It was just a placeholder, “815.” It had to be a number; why not that number? Then I found out [Lost co-creator] Damon Lindelof was reading the book and I was totally mortified. But then he thought [the reference] was funny, and I was like Okay, good. In hindsight, I probably wouldn’t have done it if I knew people were going to get it so well.

Like Lost, Mind MGMT is built around cliff-hangers and twists and big mysteries. Have you learned lessons of caution from the way Lost played out?

Oh, yeah. I get that question all the time: “How’s it going to end?” “Are you going to answer this?” “Are you going to answer that?” “Don’t be like Lost!” I have a 36-issue plan for Mind MGMT. Going in, I knew that, because I don’t like loose plot threads. I want to have everything tied up and answer everything that needs to be answered. So I’m like, “Don’t worry about it.”

What was the first element of Mind MGMT to materialize in your head? Was it a character name? A scene?

I think the title. It’s the first book where I ever came up with the title first. And it wasn’t even mine! I came up with it by stealing it from my friend David Cirillo. He’s a writer, and he had written this 600-page humorous novel. It was about these ridiculous spies and all this training they went through. They would go to classes called Disguise and Mind Management and other things. And I was like, “What’s that Mind Management class about?” And he was like, “What are you talking about?” He didn’t even remember writing it; it was just, like, a toss-off line in his book. I was like, “Alright, can I have it?” Because as soon as I read that, I was like, “Oh!”

And then I think Henry Lyme was the first character. I wanted to have somebody who was sort of this mysterious guy you don’t see. Kind of like a reference to Harry Lime [from The Third Man]. The image of Henry just walking through a city on fire and him holding this kid that he saved. That was the first image that popped into my head, and everything else was sort of built around that.

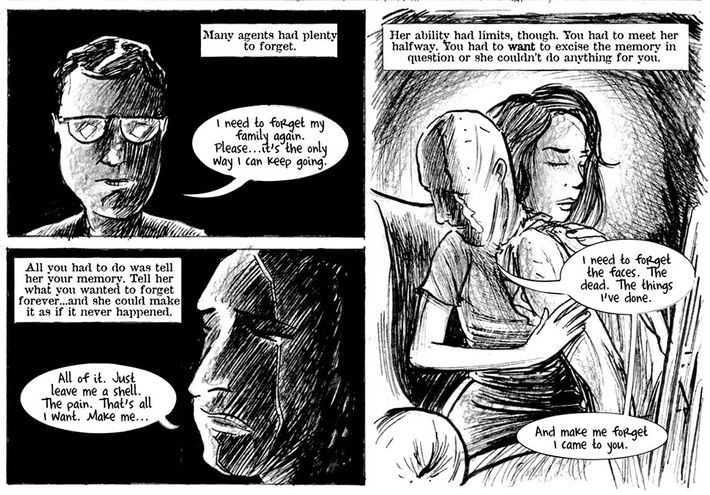

This isn’t your first series about spies. Why do you keep coming back to spycraft as a topic?

What makes the idea of espionage so great to me is that it’s like state-condoned lying. “I can do all these things that are technically illegal and immoral, but it’s okay because I’m doing it for a bigger cause or a better reason.” I think that’s always been a daydream of mine, because I’m so — I’m a rule follower. I don’t break the rules, and I follow directions, for the most part. But then the idea being able to just fly above any sort of convention and just do what needs to be done is kind of exciting for me.

Has writing spy stories made you more paranoid?

No, not really. Honestly, I’m like the most easygoing guy. I basically trust humanity, and I’m like, things are going to be fine; most people are alright. I’ll leave my bag there and go to the bathroom and come back and it’ll be there. Somebody will be watching out for me.

But I imagine you get fans at signings and conventions who are from the tinfoil-hat brigade, right? Do you get people coming up to you and saying, “You’re onto something here, dude!”

It’s funny: You asked if I’m paranoid, but I think a lot of my readers are [laughs]. And I hate that I’m feeding it, because I don’t — I think that conspiracy-theory stuff comes [from] a younger place. Like when I was in my 20s, I was obsessed with the Kennedy assassination and the unknowable nature of what really happened. And like, I would read everything and try to put all these theories together, trying to figure out what it was.

As I’ve gotten older, I’m like, it was probably Oswald and it was just a freak thing. Of course that shot is impossible, but at that one day and at that one time, that guy made the impossible shot, you know? And as I get older, I tend to lean more towards that, like, that’s probably what happened. But then in the back of my mind, I’m like, That’s what they want us to think! Maybe I am paranoid! [Laughs.] I feel like I’m sounding paranoid.

I just don’t know what to believe. In news, you get like a thousand views of the same thing. The Boston bombing was one of those things. People were like, taking all these photos, and then being like, “Who’s the guy on the roof?” And I do believe that there is an absolute truth, because the thing happened, but getting to know it is impossible. It’s impossible to know. There’ll be one event that happened, and you have like three different takes on it that are completely different. And like, somewhere in there is the truth.

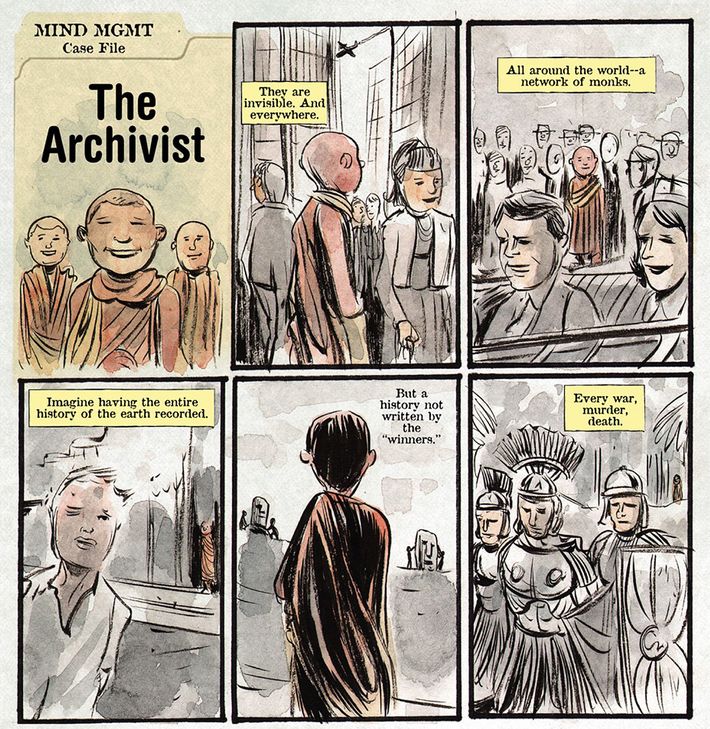

But is there really an objective truth? One of the most fascinating parts of Mind MGMT is this idea that there is a society of monks who write down the completely objective truth of all events that have ever happened. Are they a kind of aspirational fantasy for you? A hope that there can be some kind of objective truth?

Yeah, I think the monks are sort of my idea of what heaven is.

How so?

If it’s heaven, it’s going to be exactly what I want it to be or what heaven should be. It would be the monastery with the library, and the library is the truth about everything. So you could read the history of the world and know who killed Kennedy and exactly how it happened and where everybody was. All those questions that are sort of nagging you would actually get an answer and it would be the answer.

You also have these meticulously constructed bits of related text on the sides of the pages in each issue: excerpts from a character’s book, instructions for spies, and so on. How much do you worry about people skipping that stuff?

It doesn’t really bother me. When I started that, I was only going to do it for the first six issues, because it was kind of hard. As text, it has to work on its own as this mind memo, for the agents, but it also has to work in context with what’s on the page, and I thought that it would be fun to do. And it was hard to do. It was horrible! But then the reaction was so great to it. People were really responding, like, “Oh, it’s great! I can read it two or three times!” And I felt guilty. I was like, Aww, if I drop it, then people are going to be disappointed. So I would sort of throw myself into this horrible situation where I have to do it every issue.

But you can stop whenever you want!

No, I can’t, though! That’s the thing: Once I come up with an idea and I like it, or if I think it’s good, then I can’t not do it. And if it’s going to kill me to do it, I’ll still do it.

Speaking of writing: Why do you write comics? You’re clearly enamored by prose, and your work often pays homage to radio and screenplays. Why stick with comics?

I mean, that’s a good question. [Long pause.] That’s, like, a life question.

I hope I didn’t just motivate you to quit.

Yeah, now I’m doubting everything. [Laughs.] No. This is the one industry where I can have total control. I’ve done some stuff with television, and I’ve had brushes with movies and seen those industries and how they can work, and I’ve been tempted to be sorta sucked into that. But then what you realize is that there’s, like, a dozen people that want to be a part of [your project].

I feel like with comics, it’s definitely more of a lonely endeavor, but in a good way. Like, my vision and what I want is going to be what’s on the page. And I think other than, like, writing novels, it’s the only medium where you have total freedom and you do what you do and the final product is something you can 100 percent stand behind, and you don’t have anyone else’s hand or opinion on it.

And I actually think it’s better than writing prose. Because I thought about that, too. I love writing prose, and I’m working on a novel, and I don’t know. I really enjoy it and I think writing is the thing I like most, but I don’t know why I would jump to prose when comics is actually a little more lucrative. And then, at the end of the day, I’ve got my books and I can sell them for a movie or TV show without having to deal with the artistic interference.

Last thing: In the mid-2000s, you did the jacket design for Lost Girls, a fairy-tale-themed pornographic comic written by legendary genius and weirdo Alan Moore and drawn by Melinda Gebbie. Moore is, famously, a total recluse. How did you communicate with him?

I didn’t! It was all through [the publisher]. He would call me up and be like, “They want fluorescent ink, and they want it to be perfumed.” And I was like, “I don’t think that we can do that.” And he was like, “I know, I know, I’m just telling you.” We wanted to make him happy and make the good book he wanted it to be, but it can’t be perfumed. Which would be totally great! But the budget wasn’t there.

You did get the rare treat of being able to read a new Alan Moore work before it hit stands.

Yeah, I actually typed it up, because Alan didn’t have a script in digital format. All he had was this dot-matrix printout from, like, who knows when. So they sent it to me, and I transcribed it off this faded dot-matrix printout.

And it’s hard-core pornography, so you’re just typing out filth, too.

It was hilarious. I’d be laughing sometimes, because the sound effects were like “ooohhh,” “ahhhhh,” and I was like, What am I doing? Back then my studio was at home, and I had this big monitor, and I’m doing production on some of the pages, which were completely filthy, and a neighbor would come over or something and I’d have to put my screen down, because I’m like, I don’t want questions. Don’t ask me what I’m working on.