It’s hard to say what Mark Mothersbaugh is best known for — is it his New Wave band Devo? Or maybe scoring the music to dozens of movies and television shows (he’s composed the theme to Nickelodeon’s Rugrats; all of Wes Anderson’s oeuvre; and he’s worked on Pee-wee’s Playhouse)? But what you may not realize is that all of these musical exploits grew out of Mothersbaugh’s early art-school antics. He formed Devo with Jerry Casale at Kent State University, where he was spending most of his time working away in the art department print shop, around the time of the infamous National Guard shootings. Mothersbaugh’s first large solo museum show, “Myopia,” opened this fall at the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver, and with the release of an accompanying catalogue, he spoke with SEEN about the stories behind several pieces in the exhibition, and his journey from isolated weirdo in the heartland to his current life ensconced in the hills of Los Angeles.

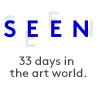

On how screen-printing in college got him into art:

I started at Kent State in 1968 and didn’t know what I was doing. I knew I had no business in Vietnam, and I’d been offered a partial scholarship, so I figured I’d give it a try. In the first year I fell in love with printmaking. Screen-printing turned out to be what I loved the most. If you went back to ‘69 and think about the availability of computers to the average person, it was pretty minimal. To me, screen-printing was the highest-tech visual art form. Without having any money, I could be patient and look at other kids waiting to dash back to frats and parties, which left me with the art department totally open to myself. In that unobstructed situation, I could work from dinnertime to 5 or 6 a.m. Early on, I started making decals. I had an interest in posting art around the campus, like people in ROTC did with posters or yippies who’d put up fliers inviting people to “Come watch us napalm a dog at lunchtime.” But I was putting up my own pieces of obscure imagery and poetry around campus. I was getting this from my earlier nerdy life of having made plastic models with decals.

I knew of no artists posting publicly purely for art. I had never heard of graffiti. I had seen “Kilroy was here.” That was the only graffiti of which I knew. I wasn’t certain why I was even doing it. I felt like I was making some sort of a statement. I wasn’t 19 yet.

Because of the decals, a grad student came up to me one day and said, “Are you the guy putting astronauts holding potatoes up around campus? My name’s Jerry Casale. I wondered what your interest in potatoes was.” We started collaborating on visual art, and then after the shootings, we started collaborating on music.

On the early days of Devo:

In the early days of putting together Devo, we found out that if you wanted to perform anywhere in Ohio, you had to perform cover songs — Box Tops, Bad Company — everything that was on the radio. When we came out to clubs and said we wanted to play original music, no one was up for that. We had to start being mischievous to get hired at clubs. We were a lightning rod for hostility. We got paid more times to quit playing than we ever did for finishing a set.

We were in Akron, a cultural wasteland, but we got Crawdaddy! and Rolling Stone. We knew about the Haight, the Village, Andy Warhol. Nowadays, that’s not astounding at all, but in the ‘70s it was not a given.

I remember Warner Brothers said they were going to print life-size cutouts of the band. They said it’d cost $5,000. We asked if we could have money to make a film for “Satisfaction.” They said, “Why would we want to do that?” This was in 1977. It wasn’t until MTV hit in the ‘80s and record companies realized it was a way to market. But if you were making art videos, they didn’t want to know about it.

On the music scene in Akron, Ohio:

There was a small scene. I wouldn’t be overexaggerating to say there were 35 people who came to Pirate’s Cove to see Pere Ubu or the club that Devo used to play in Akron. We’d have 15 people come to see us. I remember Pere Ubu, when David Thomas was Crocus Behemoth. That was a great time to see them — the best material they did was from that period, like “Non-Alignment Pact.” It was at that point that we said we could be the Residents of Akron for the rest of our lives, but we really believed in what we were doing so we figured we’d give it the acid test and try to get hired at Max’s Kansas City and CBGB’s. We played both those clubs in 1977.

If you wanted a truly totally honest answer — Liverpool, Portland, Seattle — places like that are record-company marketing maneuvers. All over the world there are creative people. In any city you go to, you’re going to find some people who are doing great music or great art. Back in those days it was just harder to connect.

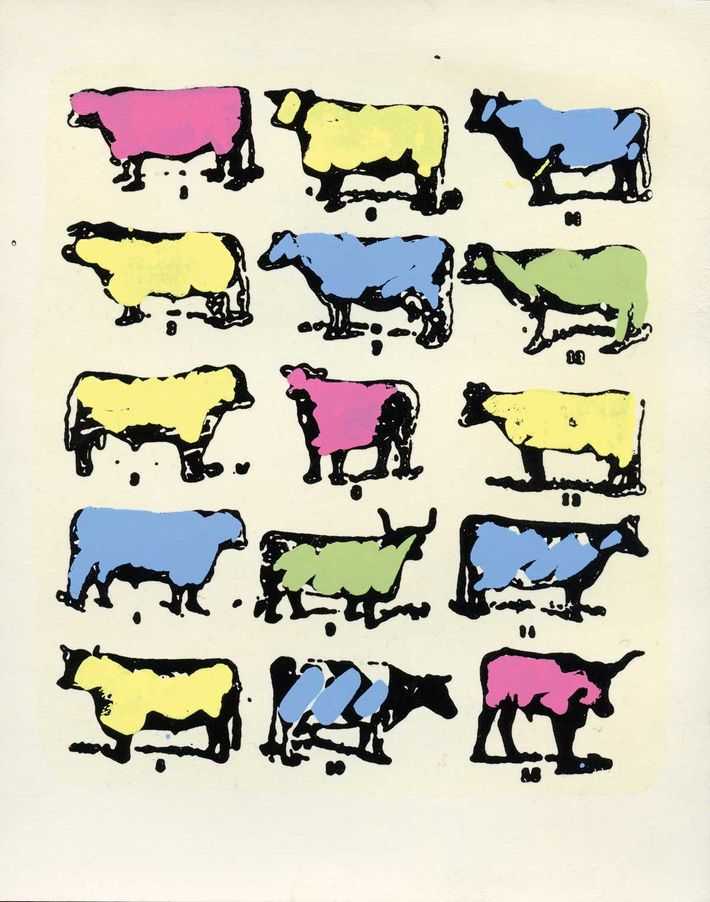

On Akron being the rubber capital of the world:

Up through the ‘70s, Akron was still referred to as the rubber capital of the world. Starting in the beginning of cars, with Ford taking over Detroit, Akron volunteered to be the rubber capital. Firestone, Goodyear, Goodrich — everyone had a factory there. They’d get shipped up to Detroit. It stunk like rubber in Akron, but that was the smell of industry. Everybody in Akron either worked in the rubber factory or their business was affected by the factory. I used that metaphor. It was kind of self-deprecating, but I liked it. The image is from pre-existing images. Right in the mid-’70s, there was a technological change in print shops around the world. They went from lettterpress to offset printing, which saved a lot of money and labor. When all these print shops made the change, you could go to print stores and find boxes and boxes of type made of steel, lead, zinc, wood — hand-carved images that these people were tossing out since it didn’t work for offset printing. I used to go scrounge for imagery. I’d load my car up with woodcuts and plates. This tire image was hand-cut out of wood.

It wasn’t until the late ‘70s that we realized something had changed in Akron. It was then that kids my age that had volunteered to go to Vietnam fought and came back. In a few short years, all of the factories closed down. It was my generation — they left for Vietnam fully anticipating working at the same factories their fathers and grandfathers had worked. Those factories were relocating to Southeast Asia or Brazil, where they could hire workers for $12 a month as opposed to $12 an hour.

On the exoticism of Ohio:

Akron, in many ways, became a motif we could have fun with in Devo. When the “Satisfaction” single first came out in Europe on Stiff Records, it went into Top 10 charts in England, France, and Yugoslavia, but we didn’t have a real record deal. On the way back from recording with David Bowie and Brian Eno in Germany, we stopped in England and played Liverpool, Manchester, and London. To people there “Ack-Ron” sounded like something out of Twilight Zone. Jerry and I would say, “Oh, it’s a factory town, overcast, gray, that it rains a lot — it’s a lot like Liverpool.” That set off Melody Maker and NME: Is Akron, Ohio, the next Liverpool? It caused a lot of A&R guys from London to come to Akron to beat around the bushes. Some people deserved the attention. Chryssie Hynde got a deal out of that.

On how his art has helped his compositions for Wes Anderson films:

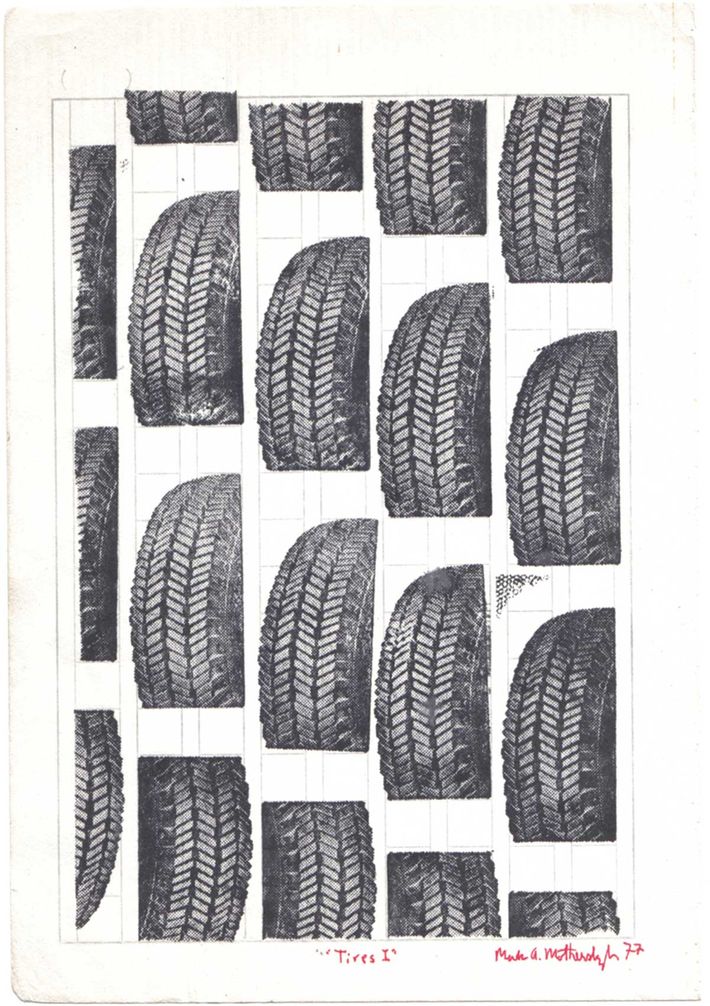

I started doing these symmetrical people in the late ‘90s. At the time, there was no such thing as Photobooth. I started using mirrors. Then I got interested in Photoshop, and I found out I could do this seamlessly. It was surprising to me that you could take anyone you know, slice their face in half, flip it — almost 100 percent of those people have one side that looks younger, naïve, beautiful, and the other side looks darker, evil, more what you would call an evil mutant. I just kept going.

I think I was doing the score to Life Aquatic while I was doing these. I’d be at my studio writing a piece of music, but I’d be thinking about the photos I was going to turn into beautiful mutants that night. Ironically during the time we were working on Life Aquatic, there was a scene in the movie where Bill Murray is talking about his boat. It’s the one time in the movie he’s happy — he’s a failed Cousteau. When he takes a tour around his boat, he’s happy. Wes asked, “Can you do something like in The Royal Tenenbaums when Gene Hackman and Anjelica Huston are walking through Central Park?” That’s the one moment when Gene Hackman is likable and happy. At this point he’s taking a walk where Anjelica is telling him she needs a divorce. All of a sudden Royal decides he’s going to be sweet to his estranged wife. Maybe we could get it together! She’s saying, That’s sweet, but I’m far beyond that and I want to have a chance with Danny Glover. Then it goes back to more problems, more duality, more deceit. Wes wanted something like that for Life Aquatic. I wrote a couple of sketches, but he said they weren’t doing it for him. Then I went home, worked on a Beautiful Mutant, and thought I’d take a bit from Royal Tenenbaums called “Yelling and Scrapping.” I held it up to a mirror and played it backward. I brought it in the next day. The melodic line was played in reverse, with changed instruments. Wes listened to it. I hadn’t told him about from where I got the music. I found out you could make beautiful mutants in music also.

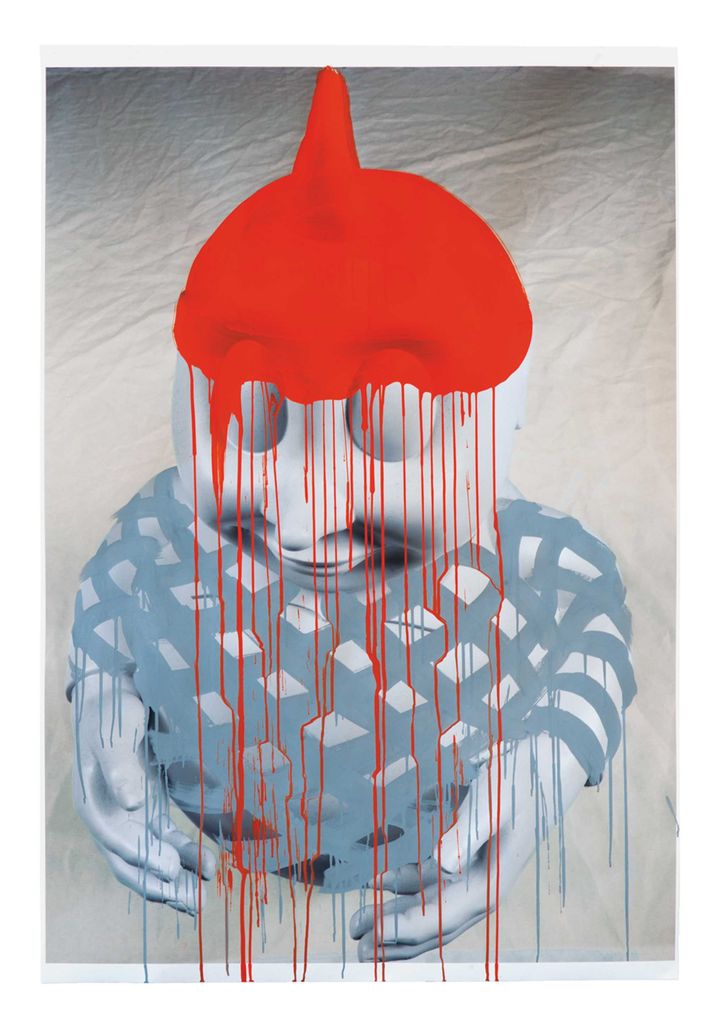

On the Roli Polis:

I started drawing them — I don’t even know how many years ago. I draw every day. It started when I was about 7, but I started collecting them into an image bank in the ‘70s. I like animation and lowbrow art. I started making my own cast of characters. The Roli Polis were another manifestation of Booji Boy, my masked character who still shows up onstage with Devo — the infantile spirit of de-evolution. It’s the one time in the show where nobody knows what’s happening. Often Booji Boy receives transmissions from the fourth dimension. We have a break in the show, Booji Boy talks; it’s funny, disturbing, and nonsensical.

I was making these Roli Polis out of fiberglass, but I had this opportunity to go to Guadalajara to manufacture them out of ceramics. I wanted to do this because they’d be like lawn gnomes out in the yard or a putti or a good-luck charm to attract good energy in the cosmos. I made about 80 of them. Then I went to Guadalajara for a museum show, but I had to paint these guys. I was painting over a photograph.

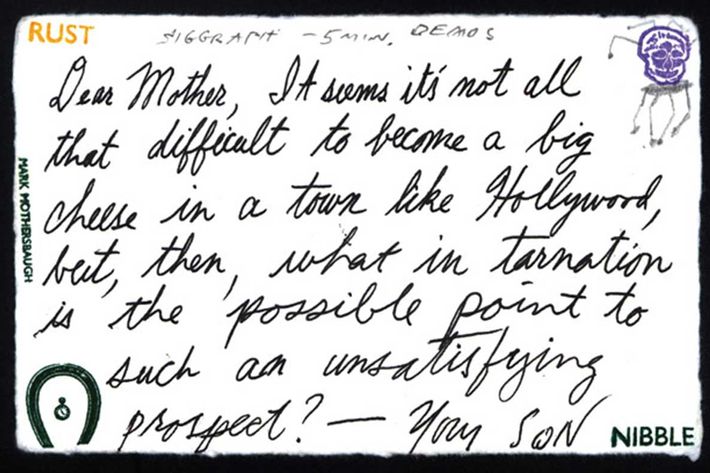

On living in Los Angeles:

Hollywood, as you can imagine, is a complex location. It’s both attractive and repulsive at the same time. Everything our paranoid visions warned us about, Hollywood lived up to it, and then some. If not for Hollywood, I would never have gotten the opportunity to work with a 100-piece orchestra or meet Wes Anderson. As much as I have to say “Whip It” wasn’t our favorite song, it was a window in. Without it, people would’ve seen our band and said, “No, I don’t want any part of it.”

I’m kind of a hillbilly. As soon as I could, I took money I got from the Freedom of Choice album and put a down payment on a house up in the hills. You couldn’t hear the city. You could see the ocean. It felt like I was able to escape Hollywood. It gave me psychological comfort since I had to work in the middle of it all. But I don’t know if I would choose to live in Hollywood if I wasn’t in the business.