If you happened to have stumbled, two Septembers ago, on a troupe of nearly 100 synchronized dancers wearing jesters’ caps in Brooklyn’s MetroTech Commons, maybe you wondered, in that split second before rushing on to jury duty, Who’s that stuff even for? You now have your answer. It was for Rick Moody.

The arts collective known as Odyssey Works stages multilayered, weekend-long art happenings, each of them designed for an audience of one. In late 2013, that “audience” was the author best known for The Ice Storm. Moody was its most famous subject to date, and the piece, titled When I Left the House It Was Still Dark, was its largest and most complex. For the first time, it wasn’t a weekend but three months of encounters, all meticulously arranged in collusion with Moody’s friends and relatives. Picture a cross between the Macbeth-meets-Myst extravaganza Sleep No More and David Fincher’s The Game — but with more improvisation.

Three weeks ago, Jason Kottke mentioned Moody’s year-old piece on his blog. A couple of days later I sat with Moody in St. Paul’s Chapel, the city’s oldest surviving church (where Moody is a congregant), to find out how it went down. He learned about Odyssey Works when a student from his Skidmore writing class — a former Odyssey subject — urged him to apply. “She said, ‘I did this and it changed my life,’” says Moody. “I’m not the kind of guy who refuses to do something that’s gonna change my life.”

Odyssey grew out of a conversation in 2001 between founder Abraham Burickson and his friend Matthew Purdon. Burickson is a former Sufi spinner and architect with an MFA in creative writing, Purdon an actor, artist, and web designer. They wanted to break artistic ground in multiple ways — to stage a piece of theater both massive and completely personal, long-running but ultimately ephemeral, which paid attention to the audience rather than demanding it from them. Instead of a mediated mass experience measured by critics or box office (“flowers or rejection,” as Burickson puts it), why couldn’t art be more like a love poem, built on intimate understanding? Odyssey Works tries to do that — and also to expand the subject’s idea of what merits attention. Rather than staring at a painting you’ve been told is important, you, the audience, are bombarded with “random” events that make you feel as though every moment might have special meaning.

To celebrate the beginning of Moody’s involvement, Burickson took him to the Russian baths in the East Village. They shvitzed, talked about spirituality, had dinner, and then Burickson abruptly left, announcing, “The piece has begun.” Soon after that, Moody had lunch with his friend Randy. Suddenly a man came up to Randy and said, “Hey, don’t I know you from Burning Man?” He pulled up a chair and started asking Moody’s advice about his ailing grandmother. Moody was amused; Burning Man Guy became a private joke.

Around that time, he was praying in St. Paul’s with his uncle Jack, a retired minister Moody calls his “extra dad,” when Jack handed over a children’s book for Rick’s daughter Hazel. The Secret Room turned out to be “premonitory” of all the major events to come. Moody was then instructed to meet Jen Harmon, an Odyssey choreographer. She led him in “fool training” — clowning techniques that reminded him of college acting classes. She was already leading workshops with volunteers, preparing for their big clown dance at MetroTech.

A week later, Moody was summoned to a vast, empty storefront in downtown Brooklyn — formerly Sid’s Hardware, soon to become Bill de Blasio’s campaign headquarters. “Sid’s Hardware was a very disturbing place,” says Moody. Once every two weeks, he’d spend a couple of hours there with a few mysterious objects: a ladder, a bag of peat moss, a bathrobe, a scarf, a hat, a teapot, a dish filled with blackberries, a half-filled diary. More satisfying was a beat-up CD rack playing a composition by Odyssey-affiliated Travis Weller, molded to Moody’s taste for atonal string arrangements. “Morton Feldman with a dash of John Cage,” he says, “which is right in my wheelhouse.”

Moody passed the time by singing. He ate the blackberries. He stared at a painting of a prairie that he recognized from The Secret Room. He wrote in the diary, sometimes in answer to existing, fictional entries. “He wrote this searing critique of the writing in that journal,” says Burickson, who wrote those entries. “Trying to impress Rick Moody with your writing is not something you want to do.” Moody told Burickson repeatedly that he found the space “annihilating” but never got a response. “We’re not against boredom,” says Burickson. “We’re not just wish-realization.”

* * *

In the 12 years since Odyssey’s first project, works built around a customized experience have mushroomed. There was Bob Dylan’s recent concert for one, Tino Sehgal’s high-concept “constructed situations,” and, on the lighter end, Sleep No More and a nationwide rash of “escape room” games. Odyssey is at once more earnest and less predictable than most of those. “There are mysteries, but we’re not gamers,” says Burickson. “Our aim is to generate the deepest experience of art that our subject has ever had.”

That requires the right subject, though, which is why Odyssey chooses them so carefully. Burickson and his collaborators read roughly 100 applications for every piece (they average two pieces a year). The five-page questionnaire asks applicants about everything from his or her favorite colors to worst fears and most vivid dreams. Moody (who “has no dreams”) worried that they would feel obligated to accept a well-known subject. Burickson says that wasn’t a major factor. Moody simply looked like an attractive left-turn for Odyssey, whose subjects tend to be young searchers. At 53, he was unusually accomplished but surprisingly open-minded. “It’s rare to find someone over 45 who was actually that open,” says Burickson.

Moody’s girlfriend (now wife) Laurel was a little less game. “Their strategic error,” says Moody, “was that they told her they were going to throw me out of an airplane because I’m terrified of heights.” Burickson says that wasn’t a serious proposal, just a red herring to test Moody’s limits. But Laurel was creeped out and didn’t want to spend three months keeping secrets. She helped Odyssey — at one point facilitating a “kidnapping” by giving them his passport — but she didn’t participate. “We’ve never encountered a partner who wasn’t 100 percent onboard before,” says Burickson, “but I don’t think you talk Laurel into things.”

They also had to keep Moody’s name quiet. Odyssey does the occasional piece commissioned by a subject but usually relies on nonprofit grants. When I Left …, which cost $25,000 (double that if you count in-kind donations), was funded by the Brooklyn-based BEAT Festival. But Odyssey never disclosed its “audience” for fear that the publicity would taint the process. Odyssey depends on total surprise, the better to confuse the participant about what’s real and what’s manufactured. “You begin to look at every interaction as though it’s suspect in some way,” says Moody. “And the action of doing that makes you pay attention to life.”

One August morning, Burickson picked Moody up at Sid’s, drove him to LaGuardia, and put him on a flight to Saskatchewan. At Regina International Airport, customs agents asked where he was staying and why he was visiting. He had no answer. “’I’m in this performance-art piece,’ what kind of crazy shit is that,” he says now. “You’d have to be a pretty enlightened customs person to let me into the country.” They only released him after he cleared the terrorist watch list. Debriefed at the end of the project, Moody objected to its “boot-camp-ish aspect.” “That was maybe why I was too old for it,” he says. “I told Abe there’s no reason to make people uncomfortable because the uncanny part works already.”

The three hours Moody spent in a straw-bale hut overlooking a Saskatchewan prairie were definitely uncanny. They were also transcendent. It was exactly the vista in both The Secret Room and the painting at Sid’s. The hut was a rusticated variation on the windowed, neon-lit dwellings of the artist James Turrell, one of Moody’s favorites. A cellist in the hut played a Weller composition for an hour before leaving him alone with his thoughts. “It was a very beautiful place,” says Moody.

The next day he was back in Brooklyn, and things were almost normal for a while. There was, though, an odd visit to his brother in Connecticut, where a woman named Xandra introduced herself as his sister-in-law’s tennis partner. “Why did I not think to ask, ‘Why is your doubles partner 28 years younger than you?’” he says. “She hung around with us all day. My daughter took a real shine to her.”

Soon Moody went back to Harmon for more “fool training.” He was instructed to wear a jester’s hat but refused (they settled on a less conspicuous red cap). He told Harmon about the pressures of finalizing his divorce, his efforts to make a new home with Laurel, and his worry that he was missing Odyssey Works clues. “I just felt like I was a big failure,” he says. He cried, and Harmon comforted him.

In the aftermath, Odyssey eased up a little. It had planned the MetroTech dance as a parade led by Moody but now concluded that would make him uncomfortable. A writer leery of the spotlight — he’d once been called “the worst writer of his generation” — might be better served by a little less exposure. They also began to structure the piece more consciously around Homer’s original Odyssey — a nod to Moody’s yearning to build a new family.

There was still, as with all Odyssey Works pieces, a grand, culminating weekend. On the Friday before it began, Moody received a printout of Michiko Kakutani’s (forged) review of “When I Left the House It Was Still Dark, by Mick Doory,” simulating the critic’s voice (and anagramming Moody’s name) and parked on a Times-like URL owned by Burickson. The writeup acknowledged Moody’s ambivalence: “The protagonist struggles to make meaning, and to reconcile his sense that he is continually missing important moments — those very moments that would allow the events of his life to resolve into some sort of order … What if the role of the protagonist is not so much to understand as to experience?”

* * *

The next morning Moody came to Sid’s one last time. There he met an artist friend and was instructed, “You can do whatever you want today.” They discovered some junked computers in the basement. “We lugged it upstairs, and we fucking destroyed it, and made a big pile of it right in the center, which reflected my dawning hatred of Sid’s.” It wasn’t planned, but Odyssey reacted cleverly. Someone ran in and told them they’d better flee before the owners discovered the damage.

Harmon then took Moody to the Williamsburg home of his bandmate Hannah, who played a Weller cello piece while Moody did some gardening with a stranger. Then the gardener took him down to Dumbo, where Burning Man Guy (of course!) walked him to the center of the Brooklyn Bridge, where six dancers in red performed while strangers dressed like clowns “mugged” Moody, replacing his keys and wallet with wooden facsimiles and a “bill of lading.” (They were supposed to take his phone, too, but Laurel had objected.)

Then Burickson rode up, and Moody asked, “So, Abe, what’s next?” Abe said, “Housewarming party?” Moody remembered that Xandra, the doubles partner, had invited him to one in Crown Heights. “And then a bunch of locks fell into place, and I realized that I’d been set up five times over.” At the “party,” where Moody’s friends mingled with strangers, “I was trying to get people to talk to me and they would just stare at me, which was unsettling. By the end of the meal, nobody was talking at all.”

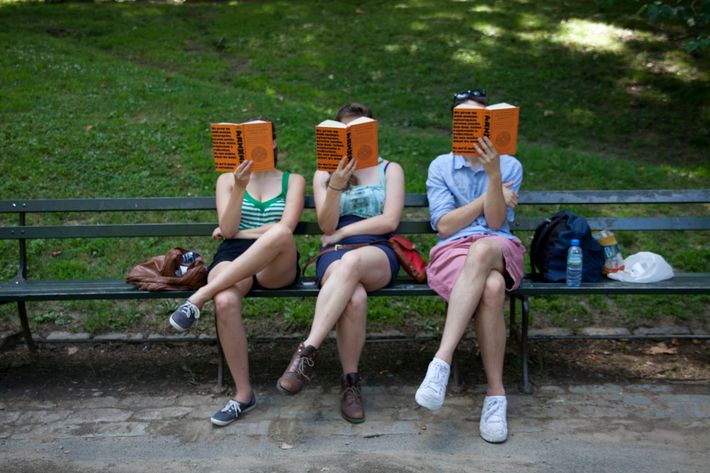

He and Harmon then took the A train to the new Fulton Center station for another dance “around all this architecture,” and finally back to Brooklyn for the MetroTech performance, where the jesters formed concentric circles around him. “Jen led them in some kind of weird, movement-oriented thing. But the real thing was that they were supposed to imitate whatever I did. Which is really fucking freaky after a while. Eventually I just drifted out.” Actually, Harmon says, he and the crowd were imitating her. She’d scrapped the Moody-led dance after their fraught second meeting. But Moody remains perplexed. “What was the message there? Lighten up? Be less serious? I’m not sure.” At any rate, Burickson rescued him, led him through a gauntlet of cello players all over downtown Brooklyn, and, “at the end of that, they put a blindfold on me and drove me to Sandy Hook.”

The New Jersey beach was actually a contingency plan. The evening was supposed to culminate on two boats anchored in New York Bay, both playing different “halves” of the Weller cello piece that would echo strangely off the waves. But the winds were too high. Odyssey counts on things going wrong. Once a subject got arrested mid-project after mistaking a real protest for an Odyssey plot. After a couple of hours in jail, the show had gone on.

Moody and Burickson settled for a sunset dinner on the beach catered by a friend of Moody’s, after which Moody was sent to a bed and breakfast along with a short story custom-written by his friend, the writer Amy Hempel. It opened with the line, “When I left the house, it was still dark.”

On Sunday, not long after dawn spread out her fingertips of rose (as Homer would have it), the B&B owner served Moody some more of the “particular foods that I alleged to like” on his application. Then his brother accompanied him on the train to Newark, where his friend Randy drove him over to Tribeca, where Moody’s 78-year-old mother was waiting on a park bench. “She’d come all the way from Pennsylvania just to do that,” says Moody. “To me, it was heartrending. So we ride to Brooklyn on the train, I tell her about the whole thing. She’s being really sweet but had to have been thinking, What the hell is this?” Moody’s father had refused to participate. At Grand Army Plaza, not far from home, Laurel and Hazel were waiting. “That moment was the Odyssean moment,” says Moody. “Odysseus comes home to Penelope and Telemachus.” All that was missing was Argos, the dying dog.

It was certainly a long journey, but what kind of art was it? “There was a lot in it that was really great for me,” says Moody, “and I was really excited to get to see them do what they do. But I reserve highest praise for Virginia Woolf. Not to be a snob, but that’s my job. If I can use a slightly degraded term, it’s more about gift economy than it is about artistic merit. It didn’t make a difference if my particular story was like The Odyssey — I couldn’t give a shit. But I was driven to look more carefully at my life and live it more carefully, and that’s transcendent in the actual sense of the word. I would recommend it to any person in a heartbeat, excepting my wife.”