Stationed above a busy corner on Canal Street, the studio of the Iranian filmmaker and artist Shirin Neshat whirred with several working film editors and assistants upon our arrival. Neshat is best known for her black-and-white cinematic films addressing gender issues within Islamic culture. She shares the space with her partner Shoja Azari*, a fellow filmmaker and frequent collaborator. Conversations in Farsi and Italian were shooting back and forth among the crew. “We are very lucky because our studio is like a community. We’re all close friends and we’re together all the time basically,” said Neshat.

Most of the studio was dedicated to editing except for Neshat’s photographic and calligraphic work area, which took over a corner of the room. Handwriting sheathed many of the figures in the photographs. Neshat has been busy with plans for three major museum exhibitions — the first opened in Doha this past November at Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art; a forthcoming exhibit will open at the Hirshhorn Museum this May; and in March 2015, she will show a site-specific photographic installation in Baku, Azerbaijan, inaugurating the first contemporary art museum to open there.

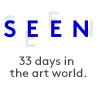

On top of her loaded exhibition schedule, Neshat has been working for four years on a feature-length film that she plans to shoot in 2015. The work is about the iconic Middle Eastern singer of the 20th century Oum Kalthoum, who died in 1975 yet continues to have a profound influence over the region. “Her music affected literally millions of people from Israel to Saudia Arabia to Algeria to Egypt to Iran to all kinds of places in the way that she sang, her poetry, and how she threw people into a state of ecstasy. But she is also known to be a nationalist and a symbol of peace. A very important symbol particularly for Egyptians today. The story is from the perspective of an Iranian artist making a film about an Egyptian female artist. It’s not really a biopic, but a very personal kind of perspective and my way of looking at the importance of this woman and her impact on other women in the region.”

Neshat pulled out a poster of another heroine, Forugh Farrokhzad, a beloved Persian poet. “Both who she was and her poetry has been a huge influence on my work and many other women. Here she is when she was young.”

Literature strongly impacts Neshat’s work, such as for her moving and highly acclaimed 2009 feature-length film Women Without Men, an adaptation of Shahrnush Parsipur’s novel of the same title about four female characters and their struggle to escape oppression. “When I shot Women Without Men, there were Iranians, Moroccans, Americans, Germans, French, Belgians, Austrians. We were making a period film about Iran in the 1950s with this kind of community of people, and at times it was a real challenge, because when you make a film, all the birds have to fly in the same direction, so to speak. But we all had a different system of working. We had different habits. Like, for example, when to break, how many hours to work. Different languages. It means we have to dance around each other’s characteristics and nature of working.”

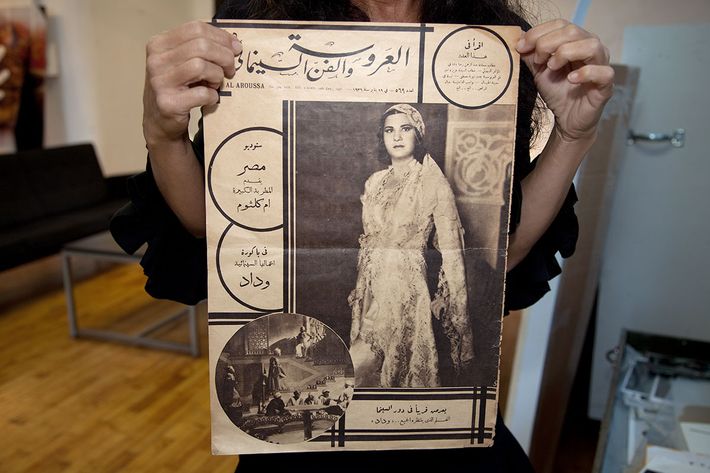

“This is a book I’ve used in a big way,” she said, opening the pages of a large vintage book. “The Book of Kings series from the 10th century. It’s an epic book of poems, mythological, about Persia before the Islamic conquest, and there were all these people getting beheaded, wars, and people who are patriotic — heroes. I used a lot of it on this new series that’s all about patriots of contemporary time. About how their lives are always in that place of violence, atrocity, and death.” She pointed to a photograph of a man. “Visually, I borrowed a lot of the illustrations that you see on his body. I bought this book at auction and someone had gone [in], a child, and put these red marks where there’s blood. The series I’m working on is 80 photographs, and it’s named after this ancient book.”

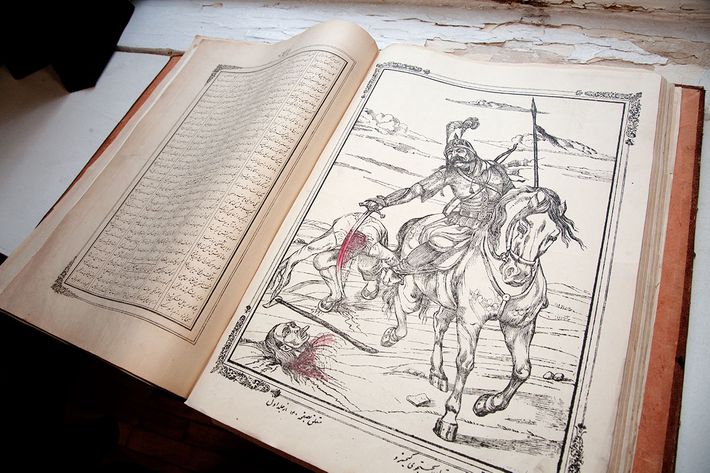

The second half of our interview took place in her home located around the corner, where more of her influential objects resided. “I have the Koran here. This is a very precious thing. All original calligraphy — all by hand — that I inherited from my parents. It belonged to my grandparents. It’s the only one I know of that has Arabic and Farsi. Usually the Koran is only written in Arabic. I’m using this a little bit for the work that I’m doing at the studio. I have a feeling this was maybe my grandmother studying the Koran, and this was maybe her homework. Sometimes she uses red, sometimes black. And that’s exactly what I do in my work. This is the only thing I inherited from my grandparents.” Born in Iran, Neshat’s family left the country for the U.S. around the time of the Iranian Revolution.

“I’m very interested in books that feed me a certain inspiration and films that constantly open my mind in terms of the subject matter or the style of the film — the form. I’m a nomad. I’m a traveler. I tend to pick up things here and there. I’m particularly interested in tribal jewelry. Things that are handmade by people and somehow are very ancient. To me they’re a work of art. I find them fascinating, how they speak to you about their history, and they’re also really beautiful. I’m also very affected by images. Photographs that I pick up here and there that speak to me and somehow eventually find a way into my work.”

She located a stack of etched metal plates. “I bought these in Iran a long time ago. They are very rare. This is where I got my ideas in terms of writing calligraphy on the bodies. These are charms. When you make a wish. Every one means something. I’m not even sure what the meaning of the symbols are. As you know in Islamic cultures, it was taboo to replicate images, for example, of the prophets, but it was allowed to draw outlines of bodies and just fill it in with words. So here, I think, is a very sexual piece of a man and a woman. He’s touching her and then there’s a fish below, which has to be about fertility. This could be a charm for someone who wants to get pregnant. Some of the writing is in Arabic and some of it is in Farsi, but I haven’t been able to make out what it means.”

I asked Neshat about her working habits and what she does to prepare for shoots. “As you can imagine, any time you start a big project, there is a lot of anxiety. You can be as prepared and scripted as you want to be, but you always wish this magic will be out there waiting for you that will help you achieve something that you’ve been really dreaming of, but you’re not really sure that that magic will be there when you get there. I think what I’ve learned is that I always arrive — whether it’s a photo shoot one day or a film that takes eight weeks — I just try to go with the flow and to be very prepared but just be expecting the most unpredictable things. Also, because we often work with non-professionals actors, the human dimension of it — you can’t really predict what type of people you will be dealing with. I just came from a week of shooting in Azerbaijan of men and women who didn’t speak the same language and had never been exposed to art. I’ve learned that tremendous bonding happens as long as you are really open to that possibility. With film, of course, it’s just like — economy. You have to be really fast, and you have to be super-prepared, but I collaborate with people who have the skills and the expertise to help me when you’re sort of stuck. Usually when you go like that it’s hardly possible you will fail entirely. Sometimes I’ll work four years on a script, shooting, and then when we edit it, it’s completely different story!” she laughed. “You have to keep an open mind.”

Listen to Neshat talk about her favorite directors, from Fellini to Linklater:

***

Neshat’s work is represented by Gladstone Gallery, New York.

Sarah Trigg is the author and photographer of STUDIO LIFE: Rituals, Collections, Tools and Observations on the Artistic Process.

* A caption in this post originally mis-identified the person in one of Neshat’s posters. It is Oum Kalthoum, not Forugh Farrokhzad. This post also originally referred to Shoja Azari as Neshat’s husband. He is her partner.