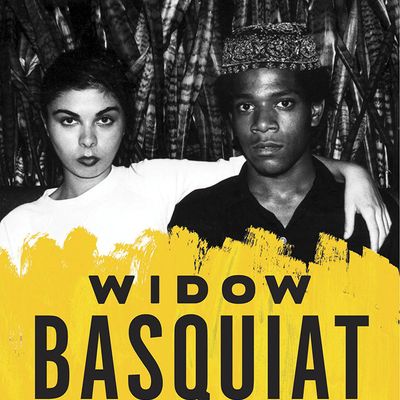

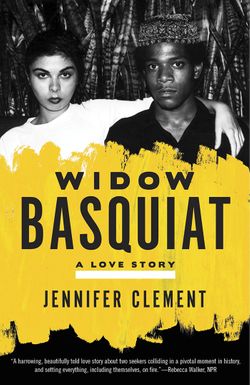

If there is one artist who has created an almost cultlike fascination around every dimension of his life, it would be Jean-Michel Basquiat. Most of us have seen how his meteoric rise as an artist was turned into a film by Julian Schnabel, starring Jeffrey Wright as Basquiat and David Bowie as Andy Warhol. But we rarely get a more intimate glimpse into his more private domestic life. In Jennifer Clement’s book Widow Basquiat, she takes the personal narrative of her friend Suzanne Mallouk — who was a longtime lover of Basquiat’s — and weaves it into a slender and poetic novella. Mallouk moved to New York City from Ontario, Canada, on Valentine’s Day of 1980. She paired up with Basquiat shortly thereafter. And as Basquiat became the New York art scene’s enfant terrible, Suzanne served as his muse, mother, and lover, struggling to sustain the both of them. She earned the moniker “Widow Basquiat” years before the artist’s death by drug overdose in 1988. Clement’s book follows Basquiat’s road to genius through Mallouk’s eyes — one lined with excessive drug use, endless nights, strangers, and moments of sheer excess — Mallouk says Basquiat was known to sometimes flutter bills into the street from his limousine. Below are three scenes of his life, as sketched by Clement.

On Basquiat’s love of both jazz and women:

Jean-Michel never reads. He picks up books on mythology, history and anatomy, comic books or newspapers. He looks for the words that attack him and puts them on the canvas. He listens for things Suzanne says and writes them on his drawings. He listens to the television.

One day he says, “Suzanne, I’m almost a famous artist now and I don’t know how to draw. Do you think I should be concerned?”

She says, “Well, just teach yourself and there will be no problem.”

Later that day Jean-Michel comes back with seven “How to Draw” books—How to Draw Horses, How to Draw Flowers, How to Draw Landscapes, etc. This was all tongue-in-cheek. He thought the books were hilarious and did several paintings where he copied the drawings.

Jean always did drugs, he never stopped. Whenever he went to Europe or Japan or any new place you could count on it that in a couple of hours upon arriving he knew where to buy what he wanted. It was like he had a radar for it. Once when he came to Canada to get me, within five minutes he was off on my brother’s motorcycle buying drugs.

His other major interest was girls, women. He loved women. He loved sex. He always had a lot of women. The only time he was faithful to me was the first few months that I lived at the Crosby loft. He had many small relationships with many different women. He would become bored quickly, though. That’s why I always had a problem knowing if I was really special to him. I still sometimes don’t know. Other people tell me I was. He once told me that the only women he had ever loved were me and Jennifer Goode.

I accepted it.

His main interest was music, though. He loved jazz, Max Roach, Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, etc. This is what he listened to at the Crosby loft. When he moved to the Great Jones loft he developed a taste for classical music (I think from Andy Warhol). He loved making experimental music. He actually put out a record that he produced and put up the money for it. The record was a rap record that he did with the rappers K Rob and Rammellzee. I think he referred to it as Rammellzee versus K Rob. He did the drawing for the cover, which was white on black. I think he pressed one thousand of them. I used to have one but I gave it away thinking I could get another but I never did.

His paintings were inspired by the jazz musicians and he felt akin to them. A lot of the early jazz artists, of course, couldn’t even walk through the front door of the hotels and clubs they were playing in and had to enter through back doors and kitchens, and I think Jean felt this was a metaphor for his place in the white art world: he had entered through the back door. He broke into the white art world in a way that had never been done before by a black.

On taking care of Basquiat at his most self-destructive moments:

Jean-Michel is made for the night, like a mole. The daylight hurts, the sun hurts, but at night he is transformed into a magician, a Merlin with everything wound up tight and sparkling. Nights are for drugs. Drugs are for nights. In daylight he looks for his shadow and crawls up inside it.

Jean-Michel stands at her doorstep. Suzanne says, “No, no, no, you can’t come back.” He is disheveled. One of the soles of his shoes flaps open and she can see his toes. He is unshaven. He brings no belongings with him. He does not expect her to take him in. Like all stray animals, he knows he will not be taken in.

I always took him in. I’d convince myself that I wouldn’t but then he’d appear with the resigned look of someone accustomed to being turned away—a boy without a friend.

When I’d take him back, which was happening all the time, I’d make dinner for him and run out and buy a really good bottle of wine, even if it took away half of my rent money. I loved to spoil him and he always appreciated expensive things, as if consuming them would make him valuable.

I would light a candle and sit him at the table. He would look at the bottle of wine for a long time.

On one of these occasions we sat together quietly and I did not know what to say to him since this had happened so many times now. We felt a bit like strangers and I made some idle chitchat and asked if his paintings were selling well. He said that he was making tons of money now. Jean drew himself up straight and said, “I am famous just like I told you I would be.”

We talked for some time of how he had always painted and how as a child he had dreamed of being a cartoonist. “The only thing that has ever interested me,” he said, “is a blank page.”

That time, for the first time, he also talked about his childhood. He told me how he had always been in trouble and had gone to so many different schools. He also told me about the time he had gone to live in Puerto Rico with his father, when he was eight and after his parents were divorced.

I guess he was lost without his mother. His mother had taken him to art museums and used to paint with him in the afternoons with both of them lying on the floor on their stomachs. She used to paste his drawings up around the house. The loss of his mother had left him with a great sadness. Even though she was now close by at the institution she was far away from him in his mind.

The next morning I gave him an apple to take with him as he was leaving. He said good-bye to me and then five minutes later he came back to the apartment and said good-bye to me again.

“You are my best friend,” he said. It was so sad. That is something children say in kindergarten.

On race — and trying to hail a cab in New York:

He smells of leather, oil paint, tobacco, marijuana and the faint metallic smell of cocaine. He wears handmade wool sweaters and long Mexican ponchos. He never walks in a straight line. He zigzags wherever he is going. Suzanne follows behind him. She feels like a Japanese woman.

Jean-Michel can never get a taxi to stop for him. Not even later when he wears an Armani suit and has five thousand dollars in his pocket. Jean-Michel hides behind a car and Suzanne hails the taxis.

He has the scar of a knife wound on his buttocks. He says his mother is in an insane asylum and that his whole world spins around her.

He moves in with Suzanne.

Jean-Michel brushes Suzanne’s hair for hours. He paints or draws. He snorts some coke. He picks up boys or girls at the Mudd Club and disappears for days. He looks at girlie magazines and masturbates. Jean-Michel likes to spit into Suzanne’s mouth.

Suzanne and Jean-Michel have terrible fights because only Suzanne is earning money. One day Jean-Michel says, “Fine, I’ll get a job.” He goes to work as an electrician’s assistant at the apartment of a rich white woman. Suzanne is so proud of him she makes him a special dinner.

When Jean-Michel gets back home he is furious, clapping his hands together. “That white bitch looked at me as if I were a worker!” he says. Jean-Michel throws Suzanne’s dinner into the garbage and does some coke. Suzanne locks herself in the closet.

It was clear that his sexual interest was not monochromatic. It did not rely on visual stimulation, such as a pretty girl. It was a very rich multichromatic sexuality. He was attracted to people for all different reasons. They could be boys, girls, thin, fat, pretty, ugly. It was, I think, driven by intelligence. He was attracted to intelligence more than anything and to pain. He was very attracted to people who silently bore some sort of inner pain as he did, and he loved people who were one of a kind, people who had a unique vision of things.

* * *

Compiled by Sam Anderson. Excerpted from Widow Basquiat by Jennifer Clement. Copyright 2000 by Jennifer Clement. Published in the United States by Broadway Books, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York.

* A caption originally mis-identified the person in the photo with Jean-Michel Basquiat. It is Suzanne Mallouk, not Jennifer Clement.