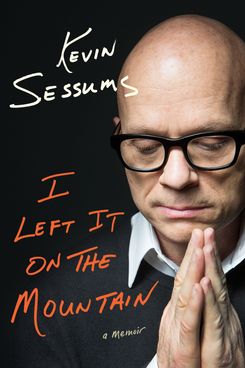

From his early days as a struggling actor, through his drug-addled years working for Andy Warhol at Interview and Tina Brown at Vanity Fair, and on to a mind-bending journey to the top of Kilimanjaro, Kevin Sessums has led an intensely colorful life — and just barely lived to write about it. His memoir, I Left It on the Mountain, is full of glitzy, debauched yarns, including the one excerpted here, about a very strange night with Courtney Love and Jessica Lange at the 1995 Vanity Fair Oscar party.

It was the night of the Vanity Fair Oscar party at Morton’s, March 27, 1995. Courtney Love was at my table since she had also requested that I be her escort that night. We had already been spending a lot of time with each other leading up to a cover story for Vanity Fair that was scheduled to run in its upcoming May issue and were by then heightened acquaintances — the kind of public relationship that can so easily flow from the intimacy that a good interview engenders when it veers into a public conversation performed as a private one.

A couple of months earlier, I had flown out to Seattle where she lived on the shores of Lake Washington. It was to be our first meeting and she had kept me waiting for well over an hour down in the living room of the house she had shared with her late husband, Kurt Cobain. I became bored going over my interview notes by the fourth or fifth time and began to inspect what appeared to be a kind of Buddhist altar set up on a side table. I opened a tiny box positioned there. What exactly could it contain? I picked up a bit of its contents with my fingers and felt the coarseness of the crinkled thread-like stuff I was holding. As I more closely inspected it — even giving it a whiff — Love entered the living room behind me and I heard, for the first time, a voice. Low. Hoarse. Hers. “What are you doing with Kurt’s pubic hair?” she asked.

I ended up conducting most of the interview with her that day as she lay naked in her tub and scrubbed her own pubic hair while I sat on the toilet with the seat down. I also spent many more hours with her on the road as she toured with her band Hole. I swigged vodka from the bottles she offered me both backstage in Salt Lake City and at New York’s Roseland. And I accompanied her to New Orleans to look at real estate. She wanted to own a haunted house as if the one back in Seattle weren’t haunted enough.

Love had graciously given me a tour of her home. She’d even unlocked a kind of inner sanctum where Cobain had committed suicide in the studio above the garage, which she’d had converted to a hothouse filled with row upon row of orchids. It was the last thing we did together at the end of a very long day there on the shores of Lake Washington. She walked me into it. Not the studio exactly. Not the hothouse. But the silence Cobain had left there. The light refracted from Lake Washington gilded it all with a silvery grayness. She touched my arm. We talked about the orchids.

Love had asked me to pick her up at her room at the Chateau Marmont the night of the Oscar party. When I arrived she was not alone but had paired up with a kind of dollish doppelgänger, Amanda de Cadenet, who was then the wife of Duran Duran’s bassist John Taylor. They were each wearing matching dime-store tiaras and were dressed in what appeared to be long lacy satin slips, as if they had tried on their gowns but then decided to discard such a bourgeois concept as clothing.

“These are the cheapest wedding dresses we could find,” she had insisted when I asked if she and de Cadenet were indeed wearing undergarments to the party. “We are gorgeous lesbians in 20-dollar dresses,” she grandly stated, then stated it again later, less grandly with more of a put-upon rock-n-roll moll in the mix, when we got to the party and she was interviewed outside by a cadre of roped-off reporters.

The flashbulbs went into a frenzy at the rope line outside Morton’s. The satin from the slips or wedding dresses or whatever they were shimmered in the shock that even those cameras seemed to be registering at such attire, the tacky gimcrackery of their tiaras exposed by the paparazzi. Forget her faux-lesbian pal de Cadenet, this was the real chum for which Love was ravenous. All their posing — chins just so, those chintzy tiaras becoming precariously unpinned — churned the chum even more. Me? I happened to be the bald gay guy who remained completely still between them.

Jessica Lange was nominated for Best Actress that night for her performance in Blue Sky. I had profiled Lange months earlier. There have been times in my job as a chronicler of celebrity that I thought I owed it to an actor or actress to write more than an impertinent puff piece. In those incidences I have tried to mine the ore of stardom, if not art, and find its seam and in so doing perhaps discover the very essence of that person. Yet even mining metaphors seemed lacking when dealing with Lange. She had recently returned to live much of the year back on her family farm in Minnesota and by rediscovering her roots she had also rediscovered the gravity one attains from the land itself, the ever onward trudge atop it, its hold on us all as we walk. There is, she had insisted to me, a mystical grounding one encounters when one is alone with one’s own undergrowth.

“That’s all I do anywhere is walk. Walking for the sake of walking,” she told me when surprising me with a phone call one morning after I thought our interviews had been completed. “But none of that silly walking,” she warned. “That power walking.”

She was piddling around in her kitchen with the phone to her ear so I asked what she had taped to her refrigerator. The piddling stopped and she read aloud the two quotes I assumed she read silently to herself every time she reached for a carton of milk or some leftovers.

The first was from T.S. Eliot:

“‘We shall not cease from exploration,” she read, “‘ and the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time.’”

She paused, seeming to gather herself before she could go on. “Then there’s this,” she said. “It’s from Kierkegaard. ‘Above all, do not lose your desire to walk. Every day I walk myself into a state of well-being and walk away from every illness. I have walked myself into my best thoughts and I know of no thought so burdensome that one cannot walk away from it. But if sitting still — and the more one sits still — the closer one comes to feeling ill. If one just keeps on walking everything will be all right.’”

When I watched her arrival at Morton’s after the Oscar ceremony, Lange was allowing herself some silly walking on the red carpet. She clutched her Academy Award in one hand then the other, its familiar heft — this was her second one after winning for Tootsie. Falling leaves, appliqued onto her sheer bodice, continued in an autumnal tumble down the rest of her gown.

Inside Morton’s, Tom Hanks held his own Oscar for Forrest Gump, and a scrum of admirers was trying to make eye contact with him. Over by the bar, Anthony Hopkins was shouting a whisper into Nigel Hawthorne’s cocked ear as if they were on some stage planning the murder of Caesar instead of standing in a din of after-dinner guests. Sharon Stone glided through the throng toward a 19-year-old Leonardo DiCaprio. Over against the wall Tony Curtis was checking me out yet again after telling me earlier that he’d once had a crush on Yul Brynner. “I think that’s why you’re making me feel so odd. You kinda look like him. I haven’t slept with a man in decades but the night is young,” he’d flirted.

I had wanted to greet Lange at the door but Pat Kingsley, her PR rep, was insisting she linger a bit longer on the red carpet. Kingsley was the toughest of a tough lot and had at one time or another represented Natalie Wood, Frank Sinatra, Al Pacino, Candice Bergen, Jodie Foster, Richard Gere, Sally Field, Will Smith, and Tom Cruise. I had a grudging respect for Pat and even liked her in spite of our adversarial roles in Hollywood.

When Lange was finally allowed by Kingsley to enter the party and she and Hanks were having a private little laugh which seemed to gather strength as it rippled through the room, I huddled at the bar with a few Vanity Fair colleagues and reached for another vodka. “ … very …” was all I heard Lynn Wyatt say to Betsy Bloomingdale as they passed by me before pausing long enough with George Hamilton to bask, along with him, in his handsomeness.

Was it Hamilton’s overly debonair demeanor that began to depress me so in that instant? Or was it the smell of vomit on the well-upholstered Anna Nicole Smith who had just thrown up in the Ladies Room yet sashayed right past me back into the party, one of her hips hitting me with such unacknowledged force I spilled a bit of my vodka? Whatever the reason the frivolity of the night began to detach itself from me — fall away. I looked at Lange across the room. Our eyes met and we smiled wanly at each other. She seemed to have been feeling the same way. She waved her Oscar-less hand at me and then her Oscar itself, trying to cheer us both up.

Michael J. Fox made his way through the crowd — nothing wan about him — and stood beside me at the bar. I had interviewed Fox for a cover story at Interview during my Factory days. We reminisced about my visit to his house years earlier. “But after that interview you left behind a piece of paper with some words on it. My dog Barnaby found it a few days later between the sofa cushions and I took it from him before he could chew it up. I’ve been wanting to tell you this for a long time,” said Michael. “It was a litany for a word association game.”

I downed the rest of my vodka.

“Yeah,” Fox said, laughing. “Every word was sexual. Pussy. Dick. Cock. Fuck. …” Michael had fun flinging my words back at me. I looked around for a lifeline. Even Courtney Love would have served the purpose if she and her doppelgänger hadn’t dumped me after dinner to disappear into the party’s swarm. Jessica Lange headed toward me just in the nick of time. As she walked up, I gave her a big hug, more in relief than congratulations, and as I did I caught a glimpse of my wristwatch. “It’s after midnight,” I said in Lange’s ear. “That means it’s March 28th. My birthday. Shit. I totally forgot. Guess it’s not about you anymore, Jessica. It’s all about me now.”

“Seriously?” she asked. “It’s really your birthday? Okay. Here,” she said, handing me her Oscar as if it were some last minute gift she’d gotten for me. “Happy birthday. Hold this. It’s getting much too heavy anyway.”

She asked Michael and me if we wanted to be her dates to the Pulp Fiction party over at Chasen’s. She grabbed my wrist and looked at my watch herself. “Pat is commandeering the limo, and I’m supposed to meet her out front in just a couple of minutes now. Come on, boys. Be my dates.”

Michael and I shrugged and followed her out to the limo. We climbed in the back with her. Michael took a jump seat. I sat next to Jessica and put her Oscar between my legs. Pat Kingsley sat on the other side of her and looked over at me with an expression of confusion and disgust. How had she been so lax as to allow someone like me in the limo with her client? The Pulp Fiction party we were headed toward was more than Chasen’s last hurrah. It was its wake. The restaurant, by closing its doors forever in just a few days, was proving that a certain sort of Hollywood was not just dying out but finally dead.

On my way to Chasen’s that night in the back of that limo I could have pretended it was the greatest birthday I’d ever had — filled with famous guests, a date who had just won the Oscar for Best Actress — but I realized it was far from it. The moment itself wasn’t exactly the saddest moment of my life — there’s been too much competition for that — but it was the exact moment that I became aware of how sad I really was, so sad I could not breathe and cracked a window to get some air. I tried to find the absurdity in the situation later and, in my diary, labeled Kingsley “The Peeved Publicist,” and Fox “the town’s latest iteration of Jimmy Cagney who sat rather irritably at that point himself on the jump seat.” And yet as I remember it now, the absurdity subsides and all that is left is how rational the sadness was.

“Roll that window up,” Pat ordered me as we pulled into Chasen’s parking lot and the paparazzi pushed toward us. She reached across Jessica and took the Oscar from between my legs and handed it back to her. Then on Pat’s cue, we all climbed from the car.

Pat cleared a space in one of the booths. Was it the one where Ronnie had proposed to Nancy? It really didn’t matter. That night it was Lange’s as she settled into it and received those who fell into her line of vision.

I resumed my spot next to her and, sitting there, allowed the night to befall mine as well. Sculpted profiles, perfected, formed taut bas-reliefs of flesh against the room’s dark knotted paneling. Courtney Love, who’d already made her way over there, loomed largest, her loudness, her dishabille beauty, causing a bit of the crowd to puddle like standing water about her. She gave me a withering stare then winked at me before throwing her head back and laughing with too much abandon.

In another cluster, Quentin Tarantino was spinning a yarn of some sort. I watched a spray of his spittle settle on the head of his own Oscar he’d won for Best Original Screenplay, beading it with little blisters of moisture as if it were beginning to perspire like everybody else in the overcrowded room. Martin Landau, who had won the award for Best Supporting Actor for his portrayal of Bela Lugosi in Ed Wood, kept letting people rub his spittle-less Oscar’s head for luck.

Landau’s own head was topped off with a toupee. With all the congratulatory jostling throughout the evening, it had begun to list to the left. Samuel L. Jackson, who had lost the Oscar to Landau, stared sourly. Sharon Stone shook an old man’s hand. Love got bored with throwing back her head at the horror of herself and came pushing through the party toward Lange’s booth. She knelt and paid homage. Lange was visibly tiring but still had enough in her to give that gimcrack tiara a couple of gentle taps, the last gesture of amusement she would allow herself the rest of the evening. I looked away from Love. I thought of the orchids.

From I Left It on the Mountain by Kevin Sessums. Copyright © 2015 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Press, LLC.