“I should have worn a suit,” says Odin Biron under his breath as he climbs the grand staircase leading from the lobby of the Moscow Ritz-Carlton to the mezzanine ballroom. He is here, wearing dark slacks and a cotton button-down, on this cold January evening to attend the 17th-anniversary party of Gazprom-Media, a subsidiary of the state oil behemoth and the country’s largest media conglomerate. He’s been welcome at these garish events for four years now, but how’s a shy kid from Duluth ever supposed to get used to this?

Lining the banisters on either side as Biron advances are statuesque women in matching pastel gowns and white sashes, each bearing the Gazprom-Media insignia and a logo for one of its 36 holdings. Dobriy vecher—“good evening”—the women intone softly as he passes, a sudden snap of happy recognition on each face as he comes into focus.

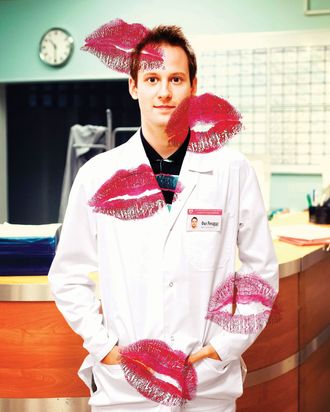

Biron is one of the stars of Interns, a hit medical sitcom watched by 3.7 million people per episode and one of Gazprom-Media’s flagship programs. On the show, he plays Phil, a bright-eyed American doctor trying to negotiate life in Russia. Interns’ phenomenal success has turned the 30-year-old Minnesotan into an unlikely heartthrob and the de facto face of America in Russian pop culture at a time when relations between the two countries have deteriorated to their lowest point in recent memory.

The TV star makes his way into the darkened ballroom and finds a spot near the back where he can stand undisturbed. Enormous crystal chandeliers hang low over the heads of beefy, taciturn Gazprom executives. They are all facing the back wall, which is covered in ultrahigh-definition screens showing promotional segments for Gazprom-Media programming. Occasionally Vladimir Putin appears onscreen to profess support for the company. Suddenly, there’s Interns’ Phil, mugging innocently in the midst of some typically madcap hospital high jinks. Sipping his wine, Biron winces ever so slightly.

He, after all, is the kind of guy who exclaims “Oh my gosh!,” loves baking bread, and plays old-timey fiddle for fun. That is to say he could not be less suited to the excesses of Russian stardom—and yet here he is, in this mock-imperial ballroom with these Bond-villain executives, watching himself ham it up onscreen.

His Interns co-star Ivan Okhlobystin, standing across the ballroom, by contrast, is the kind of celebrity who could exist only in Moscow in 2015. A tattooed nationalist former Orthodox priest, he made international news last year when he said, in a weird bit of public performance art, that he would put all gays in an oven and burn them alive. Which puts Biron in a strange position, since neither Okhlobystin or the Russian viewing public knows that he’s gay. Oh, and there’s also the fact that, Okhlobystin, 48, has become one of Russia’s most vehement anti-American loudmouths, calling frequently for the U.S. to be bombed to oblivion.

Yet when he sees Biron across the room, Okhlobystin lights up and walks over. “Odin, I’ve missed you!” he exclaims. He’s in a hurry to leave, but he promises to tell Biron the next time they meet about a recent family vacation. “We went to the Pskov Caves,” he says. “Wolf skins and wolf furs! Amazing, incredible!”

The two of them talk for a minute longer, then Biron watches as Okhlobystin summons his wife, exits the ballroom, and descends the grand staircase between the women in gowns, his full-length black fur coat sweeping behind him like a cape.

Biron has had about enough of the party too. But before we go, he mentions a Russian internet meme that’s going around these days. It’s a head shot of him under the words WHEN I ASK SATAN TO KILL ALL AMERICANS, I WILL ASK HIM TO SAVE ONLY ONE. “Gosh, it’s stupid,” Biron says, “but that’s a wonderful thing to have achieved. You have to start with something.”

Not since the end of the Cold War have Russians had a lower opinion of the United States. According to a poll released last summer by Moscow’s independent Levada Center, 71 percent of Russians have a negative or somewhat negative attitude toward the U.S. This isn’t by accident: Putin has spun the events of the past year—the Ukraine crisis, Western sanctions, the plummeting ruble—in a way that holds America largely to blame. On the major news networks, all of which are controlled by the Kremlin, the United States is depicted as a place where race riots shut down cities, children die of obesity, and all that matters is money.

Things weren’t this bad in 2010, when Biron joined the cast of Interns a few episodes into the second season. It was the end of the Dmitry Medvedev presidency, that short sunny spell between Putin I and Putin II when it was possible for a Russian sitcom to introduce Phil, a lovable heterosexual American with two gay fathers. Back then, there were no laws banning gay “propaganda.” Interns, Biron says, was the first time homosexuality was ever acknowledged in a sustained way on a Russian TV show.

The show airs on TNT, a Gazprom-Media subsidiary. Something like a cross between Fox and the CW, it specializes in reality shows and moderately trashy sitcoms about 20-somethings. Aside from Interns, which has often been among Russia’s highest-rated TV series, TNT’s biggest successes include the 4,000-episode House-2, on which contestants look for love while building a house that they then compete to live in, and Real Guys, a single-cam mockumentary set in the city of Perm about the wacky antics of a reformed child criminal and a metrosexual Tatar.

Interns follows a group of scheming, often inept medical trainees overseen by a maniacal chief of therapy, played by Okhlobystin. The humor caters to mainstream Russian sensibilities, meaning it’s darker, cruder, more cynical, and, even by CBS-sitcom standards, far less politically correct than American shows of a similar ilk. Jokes about, say, children getting a venereal disease are not unheard of. “People seem to like it,” says Biron about the show. “At times the scripts went a bit far, but I have issues with the political correctness in the States as well.”

Biron’s character is largely a compendium of Russian stereotypes about Americans. Phil, who arrived in Russia on an exchange program, is gullible and overeager. He smiles too much, tends to be preachy, and is often clueless about how things really work in the country. He’s the naïve contrast to the show’s other caricatures: the streetwise lug, the wily Jewish alcoholic, the vain playboy.

Homosexuality is a running theme on Interns. Take, for example, the episode where everyone finds out about Phil’s gay dads. Having decided to preempt the rumor mill, he delivers the information to a succession of increasingly macho Russian men and does so to the point of maximum innuendo. As a patient takes off his shirt: “I hope it will not bother you that my parents are homosexuals.” Inserting a tongue depressor: “Tell me, are you okay with homosexuals?” Shaking hands: “Hello, I’m your doctor, Phil Richards. I’m from America, and I grew up in a family of gays!”

Afterward, Okhlobystin as his superior Bykov chews out Phil for sharing what should be “a closed topic.” Phil defends himself, saying he did it “for you to know I’m not ashamed of my parents!” The patients, yells Bykov, “don’t need to know how your daddies satisfy their sexual libidos!” “You guys really have such a problem with gays?” Phil asks, his big brown eyes widening in incredulity. “No, of course not! Why would we?” screams Bykov. “We care for them so much, in fact, that we don’t let them in the army!”

Interns’ treatment of the gay topic is hardly what one might call progressive. The setup alone reinforces one of the more preposterous tenets of mainstream Russian homophobia: that homosexuality is a product of Western moral decay, a decadent import that doesn’t exist naturally in Russia. (Phil even has two gay uncles.)

But audiences love Phil. Even as he picks up more and more traits of his Russian cohorts—issues with drinking, a pervasive sense of distrust—he remains the only male character on the show who generally has good intentions. (Even if he smiles too much for his colleagues’ liking.) In a lot of ways, Phil—inexperienced, overly credulous, American Phil—has become the show’s unlikely moral compass.

Biron always wanted to act, even as a small, imaginative child growing up in rural Minnesota. “His toy box was filled with crowns and wands and gold lamé,” says his mother, Kim. When he was 5, the Birons moved into a cabin that his father, Mike, helped build on a lake about an hour north of Duluth, and Odin spent a huge part of his childhood playing there in the pinewoods.

“He liked to go out underneath the trees when the moon was on the snow,” says his father. “He took advantage of that as much as his goofin’ and dancin’ around the house. He just was a good little kid that way.”

When Biron was in sixth grade, his parents divorced, and, a couple of years later, he moved with his mother to Ann Arbor. After high school, he received a full ride to study musical theater at the University of Michigan. He excelled in his two years there but ultimately found it stifling.

“I was the musical-theater kid who was going to Butoh performances and to see Mark Rylance play Olivia in Twelfth Night,” he says a few days after the Gazprom event. Even as a teenager, he was attracted to the “jagged” and the “lopsided,” two qualities not typically associated with musical theater. Russia “seemed like the exact opposite of the musical-theater world,” says Biron. “I was looking for something more ‘serious,’ looking for more art, perhaps.”

So when Biron was 20 years old, knowing not a word of Russian, he left for a study-abroad semester at the legendary Moscow Art Theatre, the home of some of the most influential figures of modern theater: Chekhov, Bulgakov, Gorky, and, of course, Constantin Stanislavsky, the theater’s founder, whom Lee Strasberg credited as the father of Method acting. After three months, Biron explains, he was invited to stay and join the incoming Russian class in 2006, an offer rarely extended to Americans.

His lack of Russian left Biron feeling “dumb, mute, like a floating blob.” But he studied maniacally, memorizing Pushkin and Pasternak. When loneliness crept in, he burned through calling cards to talk to his family and friends. Or he would go have tea with Larisa and Elena, two older Russian ladies who work in the theater’s administration. When Biron recently went to visit them, they jumped up and took turns hugging him. “I was just Facebooking with your mom!” cried Elena.

Eventually, Biron began to stand out as an actor. He played Hamlet in one of his final roles as a student, in a production that traveled to the Baryshnikov Arts Center in New York. Soon he was fielding professional offers from places like the Gogol Center, the vanguard of contemporary theater in Russia, where he’s now starring in a successful all-male staging of Gogol’s Dead Souls.

“He hears things that others don’t,” says Viktor Ryzhakov, the respected artistic director of Moscow’s Meyerhold Center. Ryzhakov was one of Biron’s instructors at Moscow Art and later cast him as Salieri in Pushkin’s Little Tragedies at Moscow’s Satirikon Theatre. “He’s very subtle, but when he speaks, he speaks with his whole body,” he says. “I came to love him as an actor.”

Biron got the job on Interns in 2010, and that’s when “everything exploded,” Suddenly he could afford to visit his family back in the States whenever he wanted. He paid back the mortgage his mother had taken out to pay for his studies. He bought a lot of nice Danish sweaters.

His private life didn’t change much. His closest friends are nearly all the same ones he’s known since theater school. He avoids celebrity events. When he went to a nightclub with an Interns co-star, they were stampeded by Champagne-crazed women, and Biron decided: Never again.

The fame, at first, was more surreal than anything else. People stop him on the streets and women hand-deliver fan letters. They also wait outside the theater for him, shivering in furs, and line up at the foot of the stage to press roses into his palms. Once, while taking a taxi down the ten-lane highway that rings Moscow’s center, he saw himself on three massive billboards. On one, Biron was a tiny angel flying around the giant head of Okhlobystin, who looked more than ever like a cross between Bill Gates and a lab rat.

There is a long-held culture of closeting in Russia. Despite the fact that a surprising portion of Russia’s pop stars wouldn’t look out of place on RuPaul’s Drag Race, there is an unspoken “don’t ask, don’t tell” arrangement between the entertainment industry and the mainstream press. And although violent homophobia is a terrifying reality in Russia, a much more common existence, especially in Moscow, is one like Biron’s.

Biron came out to his parents when he was a teenager. His close friends in both the States and Russia, and even a couple of his television colleagues, know. But this is the first time he’s spoken publicly about being gay. It’s been relatively easy to keep his private life private. “I’ve never lied,” he says. “Journalists ask, ‘What do you think of Russian women?’ ‘Well, Russian women are beautiful.’ ‘Do you have a girlfriend right now?’ ‘No, I don’t.’ ”

Biron has been dating a Kazakhstani film director for about a year. He says it’s the “most solid” relationship he’s ever been in. For a while now, he’s been trying to think of a way to come out that would use his celebrity to the best end—“to make this count.”

In June 2013, Russia passed its notorious anti–gay “propaganda” legislation, which, though purposely vague, prohibits any perceived endorsement or public expression of homosexuality in a place where children could be present. Though Biron says he’s never felt personally threatened by homophobia in Russia, it was largely the passing of the law that prompted him to start thinking about returning to America.

Okhlobystin’s intentionally over-the-top homophobia presents its own problem. Biron has complicated feelings about the older actor. It’s hard for him to explain, but the two have forged a sincere, if uneasy, friendship. “When he’s not saying outrageously offensive stuff, I really like that man,” Biron says. “And he’s been sweet with me. He’ll say, ‘Odin, I’m gonna bomb the crap out of America, but I’m gonna save Minnesota because of you.’ ”

But when Okhlobystin made his comments about burning gays in ovens not long after the anti-gay laws were passed, Biron felt like he’d been punched in the gut. “I wanted to go to the station,” he says, “and make a statement that I would no longer work there if Ivan Okhlobystin’s going to be working at this station.”

But then he changed his mind. Or lost his nerve.

That may be part of it, Biron admits. But it’s also something else, something that goes to the core of his life in Russia. Aggressive confrontation is “just not the way I want to operate,” he says. “That’s the way things operate in the States. That’s not what this country needs. This country needs dialogue.” What good would it do if he quit Interns or left Russia in protest, he wonders. Better to stay and keep building relationships and hopefully use that foundation to help foster change. A stronger Russian gay-rights movement, Biron believes, is going to develop slowly, organically, in part through things like Interns. It’s going to happen when beloved public figures—like Biron—step out of that deep Russian closet.

“It’s the universal Harvey Milk formula,” says Anton Krasovsky, a Russian journalist and gay-rights activist. “The more likable people who say they are gay, the better gays will begin to be treated.”

Maybe. One hopes. The precedents aren’t great. After Krasovsky came out live on the air in 2013, he was fired from his job at Kontr TV, the Kremlin-backed cable network he helped to launch. Biron doesn’t know what the repercussions will be when the Russian public learns he’s gay. But talking about it now, he feels, is “forcing my hand, and maybe that’s a good thing.”

Last year, Biron sublet his apartment in Moscow, rented a place in Minneapolis, and enrolled in culinary school. Since then, he’s been splitting his time between the two cities. Mostly, going back to the life of a noncelebrity is a relief, but he misses acting and his Russian friends. He’d love to have a performing career in the U.S., but he’s wondering if food is a passion he should pursue, too. He talks of opening a restaurant, or a theater, or a combination of both. He can go on for hours about bread. “I love,” he says, “how much thought you can put into one simple loaf.”

But the simple things will have to wait. In a few weeks Biron begins shooting the sixth season of Interns. He’ll keep performing Dead Souls to packed houses. And TNT told him they’re interested in having him star in a new series about an American spy who infiltrates Gazprom. He isn’t sure if he’ll sign on. Actually, there’s a lot he’s not sure about when it comes to his future in the country. “There’s a line from a famous poem by Fyodor Tyutchev,” he says, by way of explaining his situation. “ ‘You can’t understand Russia with your mind.’ ”

*This article appears in the February 9, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.