This piece originally ran in December 2001. We are rerunning it in advance of HBO’s The Jinx, a six-episode documentary series that examines a number of unsolved crimes in which Robert Durst was a key suspect, including the 2000 murder of Susan Berman. Berman was a New York magazine writer in the ’70s and ’80s, and the following feature chronicles the mystery surrounding her death.

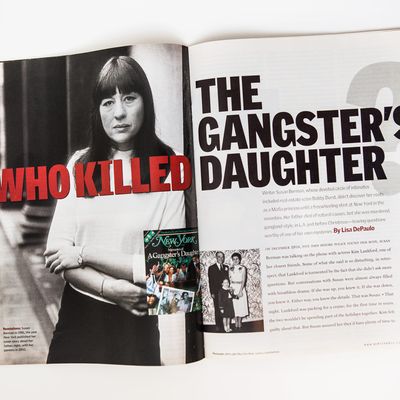

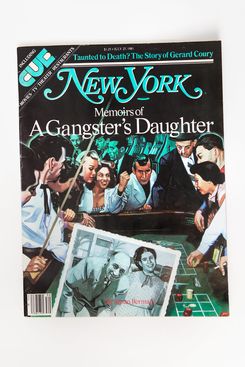

Writer Susan Berman, whose devoted circle of intimates included real-estate scion Bobby Durst, didn’t discover her roots as a Mafia princess until a freewheeling stint at New York in the ’70s. Her father died of natural causes, but she was murdered, gangland-style, in L.A. just before Christmas — leaving questions worthy of one of her own mysteries.

On December 19, five days before police found her body, Susan Berman was talking on the phone with actress Kim Lankford, one of her closest friends. Some of what she said is so disturbing, in retrospect, that Lankford is tormented by the fact that she didn’t ask more questions. But conversations with Susan were almost always filled with breathless drama. If she was up, you knew it. If she was down, you knew it. Either way, you knew the details. That was Susan.

That night, Lankford was packing for a cruise; for the first time in years, the two wouldn’t be spending part of the holidays together. Kim felt guilty about that. But Susan assured her they’d have plenty of time to celebrate when she returned, and besides, she might have big news by then.

“I have information that’s going to blow the top off things,” Susan told her.

“What do you mean?” Kim asked. “What information?”

“Well, I don’t have it myself,” said Susan. “But I know how to get it.”

“Well, be careful, for God’s sake,” said Kim.

Susan promised they would talk more after the holidays. It wasn’t unusual for her to be “about to get information”; she was a journalist. And she was working on three big projects — two book ideas and a television pilot. Two had to do with Las Vegas, where Susan had spent her childhood as a mobster’s daughter, a subject that haunted all of her work, as well as her life. So Kim assumed it was something about that. When she hung up, Kim thought to herself, Who cares who killed Bugsy Siegel?

At another point in the conversation, Susan said she’d just talked to a psychic. This, too, wasn’t unusual. Psychics were among the few things Susan had faith in. She had regular phone consultations for over 15 years with her psychic in New York, but it seemed she had seen a new one recently in L.A. “She told me I was going to die a violent death and that there’d be a gun involved,” Susan said.

Oh, Susan, Kim remembers thinking.

Less than a week later, at 1 p.m. on Christmas Eve, the Los Angeles police were called to Susan’s rundown home on Benedict Canyon Road by neighbors who’d grown alarmed that one of her three wire-haired fox terriers — so precious to her, such a nuisance to others — was running wild and barking hysterically. Susan would never have left Lulu unattended for so long. The cops found the front door unlocked and the back door ajar, and followed the bloody pawprints of the dogs to the back bedroom. Dressed in sweats and a T-shirt, Susan was lying on the cold hardwood floor, with a single bullet in the back of her head. She’d been dead for at least a day.

When friends made their pilgrimage to 1527 Benedict Canyon Road, numb with the news, they’d all remember the same grisly detail: Still on the guest-room floor, framed by the pawprints, was a clump of Susan’s lustrous, long black hair — her friends used to tease her that she kept the same sleek style, always with bangs — dried in a puddle of her own blood. “You couldn’t help but see it, it was all that was left,” says her friend Julie Smith, a successful mystery writer. “But no one talked about it, no one wanted to go near it. It was too awful to contemplate.”

It’s been over two months now, and the mystery of who killed Susan Berman has only gotten creepier and more complex — the kind of story Susan herself would have been obsessed with. When news of the killing hit the papers in early January, it shocked the literary communities on both coasts. From her impressive career at New York in the late ’70s and early ’80s to her subsequent years in Hollywood, Susan made a vivid impression wherever she went. Few, particularly in creative circles, could resist the mob daughter turned journalist with a repertoire of fantastic, almost unbelievable life stories. She also had a catalogue of bizarre fears and phobias, impossible for anyone close to her to ignore: She couldn’t cross bridges or drive on certain streets, she couldn’t eat in a restaurant without interrogating the waiters or summoning the chef (panicked that she would die from one of her countless allergies), and she couldn’t go above the third floor in a building unless accompanied by “a big strong man” and assured that the windows were “hermetically sealed” (her biggest phobia was that she would hurl herself out a window).

“She had her flaws,” deadpans Rich Markey, a comedy producer in L.A. who was the last friend to see her alive. “But her friends adored her. Everyone adored her — in spite of them, not because of them.”

And given what she’d been through in her 55 years, they also understood them. Susan had survived the Las Vegas mob of the ’50s, and one unbearable loss after another. She had almost come through the brutal downward spiral that led her from a life of enormous (mob) wealth and success as a writer to such financial and emotional despair that she resorted to selling her mother’s treasured jewelry. Through it all, she was always Susan — complicated, tormented, irresistibly entertaining.

“The way she dealt with her past was to make it theater,” says New York Times reporter Dinitia Smith, a colleague from her New York days. As the years went by, that got harder and harder. “How can I go on?” she would ask her friends. Or, her best-known half-threat: “I’m going to get into the bathtub with my hair dryer now.” Those who really knew her well didn’t worry (too much) that she’d ever take her own life. “Oh, no,” says Kim Lankford. “That was not an option. She would never want to miss how it would all play out.”

When the news hit, her history as a gangster’s daughter dominated the headlines. Could she have been killed for some mob secret she was about to reveal? A dubious theory, since most of the characters from Susan’s father’s Las Vegas days were long dead, and when she had written about them, it was with a mix of love and fascinated adoration. “If I were a gangster,” says Markey, “I’d have encouraged her to write more.”

The case took a more macabre twist when Westchester County District Attorney Jeanine Pirro announced that Berman had been on her short list of witnesses to interview in yet another eerie case, a coast away from Susan’s struggles. Nineteen years ago, Kathie Durst, the estranged wife of real-estate heir Bobby Durst — whose family’s Durst Organization owns more than $650 million worth of Manhattan real estate — had vanished in New York without a trace. For nearly two decades — as the pretty medical student’s friends spoke out about an abusive marriage and battles over money — investigators had their sights on the now-reclusive Bobby, who happened to have been extremely close to Susan Berman, going back to their days at UCLA in the late ’60s. Susan referred to Durst, who declined New York’s request for an interview, as her brother; the dedications in her books invariably began with his name. “It was always ‘Bobby this, Bobby that, wonderful Bobby,’” a friend recalls. Yet when Susan tried to reach him last summer to borrow money, she was irked to find he’d changed his phone number. So she wrote to him in care of the Durst Organization. The letter reached its target: In the months before her death, she had cashed two $25,000 checks from Bobby. In fact, Susan borrowed a lot of money from a lot of people over the years and always tried to pay it back. In this case, however, she was touched, one friend says, that Bobby had told her the $50,000 was a gift.

This past November, as a result of a lead in a separate case, the long-dormant Durst case was reopened by Pirro’s office — to a flurry of national headlines. Meanwhile, New York investigators, acting on several tips that Berman might have some critical information, sought to find her. They got there too late.

Suddenly, the “Durst connection” — Was she killed because she’d been harboring some secret about Bobby? Was he sending her cash out of kindness, or to buy her silence? — piqued the interest of the national media. By early February in Los Angeles, you couldn’t visit Susan’s Benedict Canyon home without encountering a photographer in the bushes.

Susan’s daily routine included marathon phone conversations with people she was close to — and that was a fairly large group. “If you were a friend, you were a close friend,” as one put it. She insisted you be well-versed in the characters and plots of her colorful and troubled journey, especially that of her beloved father, Davie Berman, the Las Vegas mobster who was Bugsy Siegel’s partner and who died at 53 of a heart attack when she was 12. She would write that she never appreciated the irony that he was maybe the only gangster of that era to die a natural death. More ironic was that she would be the one to die, 43 years later, with a bullet in her head: If it wasn’t a mob hit, it sure looked like one.

Her father was the “love of her life.” His FBI wanted poster was hung prominently in her living room (the phrase on it, ALIAS: DAVE THE JEW, amused her to no end), and most of her friends knew the story of his funeral, when little Susie tried to throw herself into the casket. Then came Uncle Chickie, the debonair gambler who raised her after her father’s death and who, like Susan, died broke. And of course, there was Mister Margulies — that was his real name — her only husband, who died of a heroin overdose.

And they knew all about her glamorous mother, Gladys, the onetime tap-dancer who lived in perpetual fear that her family would be killed and who had been institutionalized for depression much of her short life. When she died, at age 39 — Susan was 13 — the death certificate said “suicide by overdose.” But Susan, an only child, always believed her mother was killed by the mob for the sizable fortune Davie Berman left her. Nearly 20 years ago, when she wrote her acclaimed memoir, Easy Street, for which she diligently researched her father’s past, she’d also tried to solve the mystery of her mother’s death. Now she’d been talking about investigating that mystery again. Could that have been the big news she was about to get her hands on?

In Susan’s last days, there’d be a great many other phone conversations with the friends who’d become her family. Some troubling, some hilarious, all intriguing. Though Susan seemed to share everything, “she also kept a lot to herself,” says record mogul Danny Goldberg, a close friend who’d known her since the ’70s. “Susan was somewhat mysterious to some of her closest friends. And she had compartmentalized lots of relationships.”

Different people got different pieces of Susan’s ongoing puzzle. To some she seemed more upbeat than she’d been in years. Yes, she’d been reduced to recycling chapters from Easy Street in Las Vegas Life magazine. Still, she was convinced that, any day now, one of her book proposals or screenplays would be bought — and was relieved that she’d just gotten that chunk of money from her friend Bobby Durst to pay off her crippling debts. “Susan always was optimistic,” says another old friend, Stephen M. Silverman. “There was always a Major Project around the corner.”

Berman also seemed to be finally resolving a war with her elderly landlady, Delia “Dee” Baskin Schiffer. She complained that Baskin Schiffer would show up at the house unannounced to argue about overdue rent, the dogs, repairs; the standoff had escalated to a three-year eviction battle. Susan repeatedly told friends she was afraid of Dee and feared she would harm her dogs, Lulu, Romeo, and Golda. She said she knew Dee owned a gun. In the days before she died, however, Susan used her Bobby Durst money to settle up with Dee, even paying her rent through March, and a lawyer had worked out an agreement for Susan to leave the property by June. She told several friends she was relieved it was all finally over.

But there were also indications that, below the surface, all was not well. “She called me in October and left this long message on my voice mail,” says Silverman, an editor at People.com, “and it was so disturbing — ‘I’m on Prozac but it’s not working’ — and she desperately needed me to find her an agent. Oh, it was dramatic. I thought, this is a person in trouble. And Susan really was going through terrible times. Of course, by the time she called me back, everything was fine in the world.”

She had fretted endlessly about various ongoing dramas, from her health to her dogs to her obsession with her longtime manager, Nyle Brenner, with whom she had a fraught relationship. “We would analyze Nyle for hours and hours,” says one friend, who had her last “Nyle session” with Susan on December 21. Brenner, who friends say is the person who spoke to Susan most frequently and spent the most time with her, declined to be interviewed — except to say, “Yes, yes, I know, everyone adored her, she was remarkable and incredibly talented. But she was not an easy person to get along with, okay?” Reached a second time, Brenner hissed, “I’ve got other clients to take care of, I don’t have time for this … I was tapped out by Susan every day while she was alive, and it’s the same thing in her death. I just can’t take it anymore.”

There are scars within me that will probably never heal; I have uncontrollable anxiety attacks that occur without warning, I am never secure and live with a dread that apocalyptic events could happen at any moment. … Death and love seem linked forever in my fantasies, and the Kaddish will ring always in my ears.

—From Easy Street

Susan was 32 — and already a successful journalist — before she began to believe her father really was a gangster. She’d begun her career in the ’70s at the San Francisco Examiner, creating quite a splash with a magazine cover story headlined, “Why I Can’t Get Laid in San Francisco.” Despite her obvious intelligence (not to mention her career as a reporter), she’d managed to hold onto her innocent memories of Davie Berman — the man who took over Bugsy Siegel’s “operations” at the Vegas casinos in 1947 when Siegel was gunned down gangland-style (and Susan was 2).

That changed after one too many New York colleagues asked if she was related to the notorious gangster. In 1977, she became obsessed with finding out everything — traveling back to Vegas and her father’s hometown of Ashley, North Dakota, using the Freedom of Information Act to get crateloads of FBI files about her daddy. It was all there: the bank robberies, the kidnappings, the killings, and those unknown years before she was born, when he’d spent seven years at Sing Sing.

Easy Street was published to raves in 1981 and bought by Universal Studios for $350,000 (the movie was never made, a long-standing source of disappointment to Susan). During that time, she wrote for New York — though never in the office, of course; it was too high up — penning clever and sassy articles on everyone from Bess Myerson to herself (she wrote at length about her phobias, which didn’t kick in until she was 27 but flourished in Manhattan).

“She was certainly the most brilliant person I ever knew,” says a friend from that time, Über-publicist Liz Rosenberg, part of Susan’s posse. The group included Saturday Night Live star Laraine Newman, Danny Goldberg, New York writer Julie Baumgold, and, to be sure, Bobby Durst, who was working for the family business and enjoying the life of a real-estate scion at the time.

Spellbindingly funny and capable of dishing with the pros, Susan became a darling of the New York literati, hosting dinner parties at her Beekman Place apartment and entertaining friends at Elaine’s, where she usually picked up the tab. Her first apartment, a tiny studio, had only a shower, recalls Stephen Silverman, who lived next door. “So Susan would put on this Madam Butterfly Cio-Cio-San bathrobe and walk out on the sidewalk, come into my building, and go right into my bathtub. Whenever she wanted! I could be screwing my brains out, Susan would just barge in.”

Susan had inherited some of Davie’s fortune, in the form of a trust fund, and friends say she spent it like it would never end, dressing in $400 St. Laurent blouses bought three at a clip from Saks and boots that she liked to buy in sets of two.

The only snag was the Easy Street book tour. “An absolute nightmare that required all this elaborate planning,” remembers one colleague from that time. Her publisher had to jump through hoops to find hotel rooms below the third floor and circuitous routes to avoid tunnels and bridges. Once, she wrote in New York, she was mugged at knifepoint by a gang that tried to force her into a car heading for Brooklyn, where she was certain she would be raped. She managed to escape: No fucking way was she driving over the Brooklyn Bridge.

Susan was, as Silverman puts it, “a lot of work.” She was famous for fallings-out with people that could last for years. “If you pissed her off,” says her adopted son, Sareb Kaufman, “she was like, ‘Fine, you’re out of the Rolodex. You obviously have an issue.’” But she also took no small pleasure in directing the lives of everyone in her circle. Bede Roberts, who’d known her since her Berkeley days, remembers telling Susan she fancied a man on campus who’d jilted her. “’You really want this guy, you’re sure?’ Susan asked. ‘Okay, I’ll get him for you. But you’ve got to do everything I say, nothing more, nothing less.’ Susan plotted the course of his breakdown with exquisite precision.” And he married her.

Despite all she learned about her father, Susan continued to worship the memory of Davie Berman. In New York, she carried his mug shot in her wallet and would “whip it out, the way the rest of us showed baby pictures,” Dinitia Smith remembers. To Susan, her father would always remain the doting, charismatic figure who rushed home from the casino every night to read her a bedtime story (and then returned to count the house take), who filled an entire room with toys and gave her a house account at age 7 so she could order shrimp cocktails from room service, who commissioned an oil painting of her in pigtails to hang in the lobby of the Flamingo, who taught her to play his favorite song, “The Sunny Side of the Street,” on the piano, and who held Passover seders in the casino showroom. Through the years of her childhood, Davie Berman, not Elvis (though she did know Elvis), was the King of Vegas, and Susie was his princess.

With his wife in the mental hospital, he’d pick Susan up from school and help with her math homework in the counting room, using casino chips. He taught her how to play gin at age 4, so she’d have something to do with the bodyguards who lived in their house (she grew up thinking they were friends and uncles, and took great pride in beating them). It wasn’t until she researched Easy Street that she realized who those gin buddies were. Or why the windows in their custom-built house were so high off the ground (to keep from being shot at from the street). And why they never had house keys (mobsters didn’t keep them, to protect their families in case they were killed; the bodyguards took care of the door). And why she would be whisked away in the middle of the night to the Beverly Wilshire Hotel in Los Angeles. She thought these trips were family vacations and loved the ice-cream sundaes from room service, when in truth it was to protect her when there was mob unrest.

A month before her father died, he threw her a lavish 12th-birthday party at the Riviera. Liberace sang “Happy Birthday” to her. In order to produce friends for the party, Davie invited the daughters of other Las Vegas hotel owners, few of whom Susan knew.

Within hours of Davie Berman’s funeral in 1957, the mob had cleaned out her house and given away all her toys. She was shipped off to Idaho, with a single trunkload of clothes and mementos, to live with Uncle Chickie. Later, she was sent away to various boarding schools, her education broken up by regular visits with Chickie in jail. He would ask her to wear Chanel No. 5, she wrote, so he could “smell the real world.”

In 1981, a long excerpt from Easy Street appeared as a cover story in New York. Within two years, Susan left New York City; high on the film sale and flush with cash, she had decided to move to Los Angeles and become a screenwriter. She bought a black convertible and headed off to the city that had been a refuge when she was growing up. Two months later, while standing in the Writers Guild script-registration line, she met Mister Margulies. He was 25 and broke. She was 38 and Susan Berman. “I know you,” he said. As she later wrote, he recognized her from the pictures on the back of her books. Mister’s father had them all because he worked for Davie Berman in Vegas. “He loved your dad,” Mister told her.

In no time, he’d moved into her Benedict Canyon home — the same one she would return to years later and die in. In those days, it was a lovely, cheerful place; Dee Baskin Schiffer kept it up then, according to Susan’s friends. “And there was love in the house,” says Kim. “They were crazy about each other.” In June 1984, in a lavish wedding at the Hotel Bel-Air complete with ice swans (like the ones Davie the Jew insisted on having at the Flamingo), she married her Mister. Bobby Durst gave her away. Film producer Robert Evans toasted the couple. Susan footed the bill.

Soon after, she bought a beautiful home in Brentwood. The marriage lasted little more than six or seven months. “She called me crying and said, ‘It’s over,’” says Julie Smith. “I said, ‘What, Susan?’ She said, ‘He’s been doing drugs again and he’s been abusing me.’” Susan knew when she married him that Mister had done heroin in the past, but she believed it was over. Susan was naïve to the point of being puritanical about drugs, say her friends. Despite the pain in her life, she never self-medicated. “I don’t think she ever smoked a joint in her life,” says Lankford. “The only alcohol she ever drank was a glass of wine at Passover.” This too came from her father, who told her that drugs and alcohol “were for suckers” and not something Jews did.

They had already divorced when Mister overdosed, at age 27. At the time, she believed they were reconciling, and his death led her to a nervous breakdown. “Did he meet the doom meant for me?” she later wrote. Her psychic, Barbara Stabiner, met her shortly after, when a mutual friend called her in New York because Susan was on an L.A. rooftop, threatening to jump. Stabiner talked her off the roof by reading her tarot cards and seeing great things in store.

In 1987, she met the man who friends say was the last real boyfriend in her life. Paul Kaufman was a financial adviser with Hollywood aspirations and two young children. They all moved into Susan’s Brentwood home (up the street from Nicole Brown Simpson’s townhouse). And for a while, he made her happy. What made her happier were his children. Mella and Sareb, now 24 and 26, consider Susan Berman their mother. “She held my hand through everything difficult in life,” says Sareb, who works in the recording business. “She was the only person who was always on my side and never judged me.”

Her relationship with Paul ended in 1992 — around the time Susan went broke. The bank took her house and she had to declare bankruptcy. Friends say the couple came undone by a project they tried to do together — a Broadway musical based on the Dreyfus affair. To finance it, they used Susan’s assets. The musical never got off the ground. The relationship failed. Susan had another breakdown.

But Mella and Sareb would continue to be her children. “Being a mother to these kids was one of the proudest and most satisfying things in her life,” says Rich Markey. In 1992, a friend gave Susan, now penniless, use of a condo on Sunset Boulevard. While Sareb stayed with his father, Susan and Mella lived there for five years for free, and Susan started writing mysteries to pay her expenses and Mella’s private-school tuition. She and Mella also co-wrote an unpublished book manuscript, titled Never a Mother, Never a Daughter. Susan always wanted children of her own; at one point, she talked with her friends about asking Bobby Durst to father a child with her.

The biggest thing to come out of that period was Susan’s return to Las Vegas: A book and an A&E special called Lady Las Vegas brought her new acclaim and fresh cash (and showed, perhaps, a lack of caution, since she’d once told Julie Smith that, after Easy Street, she’d been warned, Don’t ever mess with us again). Finally back on her feet, she called Dee Schiffer and asked if she could move back to the house on Benedict Canyon Road.

By then she had also acquired a manager, Nyle Brenner, whom she’d met walking her dogs on Sunset. It would prove to be a strange and intense relationship. Susan was the only writer Brenner represented; the rest were primarily struggling actors. It was lost on no one that Nyle was a ringer for Mister Margulies. Friends say Susan would call him constantly to help deal with her now-raging phobias. He ferried her around to do her shopping and to her doctors’ appointments (Susan always had a litany of medical worries) and to the vet (the dogs did, too). When he’d get fed up, she’d tell him, “Fine, leave.” At which point, according to her friends, Brenner would grovel and beg her to keep him. He later told one of Susan’s girlfriends that “she was like an addiction.” So was he.

Though Susan’s friends believe Nyle lacks any particular interest in women, she was determined “to get him in bed, she was so in love with this guy.” Her obsession led to several painful and humiliating experiences, but she couldn’t let it go.

By the end of Susan’s life, many of her friends believed the relationship had gotten even more volatile. Markey, who gave Susan an old couch a few weeks before she died (she could never afford furniture), recalls that when she asked Nyle to fetch it, “I could see on his face, the last thing in the world he wanted to do was to haul a couch down a staircase for Susan. But he did it.” Others say that in her last few days, she was upset about an incident that had happened recently. Susan had surgery on her eyes for glaucoma, which to her “was like open-heart surgery,” says a friend. Nyle was in charge of taking her for the procedure and “making sure that she didn’t fall on the way home.” Of course, she did fall.

On December 22nd, Susan’s last night alive, she went to dinner and a movie with Rich Markey. Using their Writers Guild passes, they went to see Best in Show, the dog-show comedy, and Susan laughed uproariously through it. Over dinner, after Susan did her usual grilling of the waiter, they talked about her book deal, her TV deal, Sareb and Mella. Susan was particularly excited about a sequel she was planning to Easy Street, called Rich Girl Broke. Markey was on his way to Vegas for a family reunion and Susan was delighted that he would see where she grew up. On the way home, she had a fit in the parking garage because someone in the elevator pressed 5. It was a normal Susan evening.

The police believe that she was killed the next morning, Saturday the 23rd. When they arrived on Sunday, her mail hadn’t been brought in yet, though Susan (and the dogs) never missed the mailman. Word first got out when Susan’s cousin Deni Marcus called and a homicide detective answered the phone.

The person who would have been notified first was Sareb, who lived nearby and talked to her daily. But he was traveling in Amsterdam; it seemed as if everyone was away. When Susan didn’t call him on Christmas Eve — a night they always spent together — and didn’t return his calls, he feared something horrible had happened. “Even if she was laid up in the hospital,” Sareb said, “she would have called me.” In the last year, she and Mella had become estranged. It bothered Susan terribly, and she worried endlessly about Mella. At the same time, she had rewritten her will and cut her out. Not that there was much left, besides mementos and the rights to her work — though they may well have grown in value since her death. She left the rights to at least one of her works to Nyle Brenner.

It wasn’t until the following night that word began to spread to Susan’s close circle. She was expected for Christmas dinner at a friend’s mother’s house. Susie Harmon, her chum since boarding school at Chadwick (where schoolmates included Jann Wenner and Liza Minnelli), lived in Arizona, but Susan joined her every Christmas night at her mother’s in Los Angeles. This year, she was bringing Nyle Brenner with her.

When she didn’t answer her phone all day, her friends panicked. Nyle drove to the house. By this point, the police had already removed the body; they had also locked the house up. Later, Nyle would tell friends that when no one answered the door, he crawled in through a back window.

Nyle apparently gave different accounts of what happened next to different people. He told some that he knew something was wrong when he saw “black dirt” all over the house (fingerprinting dust left by the police). He told others he looked through the house and “nothing was amiss” (did he miss the hair and blood?). “What struck me as odd,” says one friend, “was that he told me that he walked out the front door, went to the neighbors, and said, ‘Is anything wrong next door?’ They said they were sorry to tell him that the woman next door had died. Nyle told me, ‘Well, of course my heart broke. But I realized she was clumsy, she could have fallen down. And I got back in the car and drove to Susie’s.’”

Most of Susan’s friends got word of her death from Nyle, who left urgent messages on their machines. When they called him back, he told them what had happened, that Susan was dead and had been murdered “execution-style.” When Sareb got the news, he flew back from Amsterdam. Nyle met him at the airport and spent the ride home telling him how difficult his mother was.

Things got stranger at the memorial service Sareb arranged for Susan in early February. He held it at the Writers Guild and banned members of the press who weren’t friends of Susan’s because he wanted Bobby Durst to be able to attend without being harassed by the media. (Durst didn’t show.)

Sareb asked nine people to speak about Susan, and the stories they told were beautiful, funny, and touching. But this was a group filled with writers — mystery writers, screenwriters, journalists — and so, before and after the service, as cocktails were served, they couldn’t help but ask the one question on all their minds: “Who did this?”

This was the night that several people had what they later described as unsettling conversations with Nyle Brenner. “At least I won’t have someone calling me three times a day,” he said to one attendee. “She sucked me dry,” he told another. But there has also been much discussion among her friends about what Susan really knew about Bobby and Kathie Durst. One told New York that many years ago, Susan revealed that “she’d provided Bobby’s alibi” — while insisting it did not mean she thought he was guilty.

The cops have the hard drive to her precious computer, and sources say it is rich with clues. Her Rolodex — reputed to contain over 1,000 numbers — is also being pored over by investigators. New York has learned that the police have also obtained Nyle Brenner’s files. No gun has been found. But a bullet casing found at the scene — and reported to have been from a small-caliber gun — gives investigators a shred of hope. It is widely theorized that whoever killed her was someone Susan knew — or a professional hired by someone Susan knew —whom she trusted enough to let into her home, or who knew enough about her to get into her home. Susan, with all her fears and neuroses, would never have let a stranger in.

The LAPD is keeping a tight lid on details about the case. And friends say privately they fear it may never be solved. Or worse: “that it will,” as one puts it, “and it will be one of us.” Bobby Durst is included in that category. And for that reason alone, many of her friends — though fully aware of “the coincidence,” as they refer to Jeanine Pirro’s plan to interview Susan — just don’t buy the Durst theory. Susan lived by a moblike code of loyalty. She would never, no matter how desperate, rat out a friend, even if she did know something incriminating. (“If she could compartmentalize Davie the Jew,” one friend noted, “she could compartmentalize Bobby Durst.”) The answer to the question “Who shot Susan Berman?” may well prove to be, “None of the above.” As Liz Rosenberg puts it, “She could have pissed off a total stranger.”

On January 2, Susan was laid to rest in a huge mausoleum at the Home of Peace cemetery in Los Angeles. She was dressed in a long black velvet dress with white trim that had belonged to Sareb and Mella’s grandmother and was placed in a vault next to her parents and Uncle Chickie. “Fortunately, it is on the second level,” says Kim Lankford. “And there’s nobody on the other side to annoy her.” Together, some of her friends sang “The Sunny Side of the Street,” and had her favorite photos placed in her casket. “We put all her favorite people in there,” says Kim. “Couldn’t fit everybody in.”