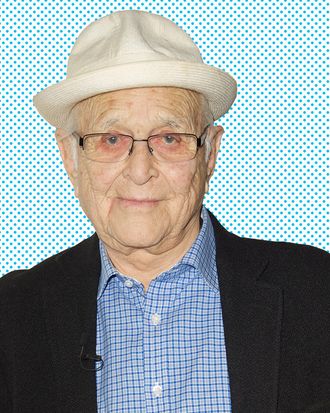

Norman Lear was a celebrity producer of television sitcoms decades before the current era of superstar showrunners dawned. His string of Nielsen hits during the early- to mid-1970s — All in the Family, The Jeffersons, Sanford and Son, One Day at a Time, and Maude — made him one of Hollywood’s most powerful creatives. At one point in 1976, nine shows produced under the Lear name were on TV. But beyond his ratings success, Lear became an icon as much (and perhaps more) because of the kinds of comedies he made. His were shows that “employed the power of humor in the service of human understanding,” as President Bill Clinton put it when presenting the producer with the National Medal of Arts in 1999. “He held up a mirror to American society and changed the way we look at it.”

While Lear, now 92, hasn’t produced new TV shows in a while, he remains an incredibly active nonagenarian. He’s toured the country since last fall promoting his autobiography, Even This I Get to Experience. Last winter, he popped on the The Daily Show. And this month, Shout! Factory released Maude: The Complete Series, a handsome 19-disc collection of all 141 episodes of Lear’s landmark half-hour starring Bea Arthur as unapologetic feminist firebrand Maude Findlay. We caught up with Lear recently to talk about his memories of Maude, reports that All in the Family and One Day at a Time might soon be rebooted, and his worries that American may, in some ways, be a more conservative country than it was in the 1970s.

So, during the recent hullaballoo surrounding Saturday Night Live’s 40th anniversary, VH1 aired a marathon, and I caught the episode you hosted. I loved the routine you did with your daughter.

You saw the routine?

I did, yes!

[Lorne] cut it [from the reruns]! What happened was, he came up to me just before I was going out to introduce this routine and my daughter. He said to me, “We’re running long. We have to cut it and go to the film.” And I said, “Okay”— fully intending to [cut it], because he was my producer. And I walk out, and there’s enough light to see the first two, three rows. And there’s my daughter sitting there with this anticipatory look on her face. Ringing in my head is my producer saying, “Don’t.” And sitting in front of me is my daughter’s face saying, “Do.” So I did. It was live! There was nothing Lorne or anybody could do about it. And we did it! It went live on the air, and I have a copy of it. But he cut it later and put what he wanted in there.

I guess he saved the tape, because I saw it just the other week on VH1. So it’s back!

Oh, I’m thrilled to hear that! I didn’t know that.

Did Lorne yell at you afterwards?

No, no. There were no words said. He wouldn’t yell, anyway. But it was clear he was upset — as he should have been.

So Maude, of course, originated on an episode of All in the Family. When you planned her first appearance on All in the Family, did you think that the character might be a potential spinoff?

Oh, absolutely. I knew [Bea] very well. When I did the George Gobel show — this was a few years before All in the Family — I brought her out to guest-star several times. And also, we were friends, so I knew her very well.

And the response to her guest appearance on All in the Family was instantly very positive, right?

As the show was going off the air in New York — the credits were still running in New York — somebody from my family was calling me to tell me how great the show was. But it had to wait, because Fred Silverman, [the head of entertainment at] CBS, was on the phone. He said, “There’s a show in that woman.” Which, of course, we very well knew. But Silverman wanted a pilot.

One of my favorite episodes of Maude, and one of the most powerful, is “The Analyst.” It’s just Bea talking to her unseen psychiatrist for the full episode, and talking about how her [spoiler alert!] father shaped who she was. It would be amazing to do that episode today, let alone 40 years ago.

The genesis of that is one of the greatest personal stories in my life. I was 16, maybe 17 years old. I was in love with a play called Liliom, by Ferenc Molnár, which later became, many years later, Carousel. It was playing at the Westport Playhouse in Connecticut, and it was starring Tyrone Power, who was a great, big star at that time, a motion-picture star. He was married to a woman called Annabella, one name, who was also a big star. And they were starring in it at the Westport Playhouse. And my girlfriend was Charlotte, she became my wife later.

This was all before the war, and I was a senior in high school. And I got tickets. I owned a Ford Model A. I was gonna drive to West Hartford and pick her up. My father said to me, “I’ll be home in time to let you have my car,” which was a new Studebaker. He was gonna give me his car, because he knew how important this was. So, let’s say 3:30, he said he was gonna be home. At 3:30, he wasn’t home. Quarter to four, he wasn’t home. Five minutes to 4 o’clock, I got in my little Model A and I drove to Hartford to pick up Charlotte. I’m on the Parkway, having gone through Middlebury, Hartford, and New Haven. I’m 20 minutes or so from Westport, and there’s a honk, honk, honk, honk. My father has caught up with me. [We] change on the Merritt Parkway, and I take his Studebaker the rest of the way, and he drives home in my car. It was the closest moment I ever had with a guy who went to prison when I was 9 years old, who was gone for three years. He was not a great father, ever — except for a couple of those flashy moments. This was the single biggest thing in my life.

And this inspired the episode.

I wanted to do that with Maude. The way we did that with Maude was that she came into her psychiatrist’s office, being bitter about something that happened with Bill Macy — with her husband, Walter. In the course of which she remembers her father did something, and she says, “Oh, I hate my father.” And then as she’s talking about her father, she remembers this moment, and she winds up relating the moment, and crying, and saying, “Oh, how I love my father. How I love my father.” She feels at the end of all of that that her therapy is complete. This is the moment that kills me: She says that to the doctor, “Well, it’s been three years or something, but I guess that’s it, Doc; I know what I need to know.” And she walks to the door, and then she pauses. She says, “See you Tuesday.” The “See you Tuesday” just lives with me forever.

One of the coolest things on the DVD set is the syndication pitch reel, where you’re basically selling Maude to local TV stations. It’s amazing you had to convince anyone to buy such a classic TV show.

You know that story?

Which story?

Selling the show to syndication, and the help I got from Betty Ford.

No! Please tell me.

Our guys couldn’t sell it to syndication. The guys who were buying for their station groups would say, “I don’t need that old ball-breaker on my network” — and that was the way it was going. There was going to be a NATPE — a [syndication] executives’ conference — and I had a thought. Betty Ford, when she was in the White House, she [sometimes] needed to get the [videotape of certain episodes]. So she’d write me, and she signed every letter “Maude’s No. 1 Fan.” So I called Maude’s No. 1 Fan and said, “Mrs. Ford, we’re having the most difficult time selling Maude, and if you’ll excuse the language, this is what I’m hearing.”

The station managers calling Bea a ball-breaker.

That infuriated her. And I said, “I can get a lot of these guys to come to a dinner party if you will co-host with me, because that will be really impressive.” And she said, “Give me three dates and I’ll pick one.” So the invitation went out that this was a Betty Ford and Norman Lear and Bea Arthur invitation. It was … a dinner party out on the lawn in front of my house, and my wife and my daughter were hosts, along with Betty Ford. The guys danced with her [until] close to 1:00 in the morning. That’s when I said to the Secret Service people, “Get her out of here! She served, she doesn’t have to do any more!” But she was so happy to have been there. So the next morning, we had a meeting with the same guys who were there that night — and we sold the show.

I love that the wife of a Republican president helped one of Hollywood’s most famous liberals sell his show.

I also did a [special] called I Love Liberty, and Gerald Ford and Lady Bird Johnson co-chaired. That’s the only way I could get it on the air, because they knew me to be a liberal. And I said, “This was going to be about America, about the flag, and who owns it.” I think it’s everybody’s, and not just the right wing. The only way the network would do it was if I got Gerald Ford and Lady Bird Johnson to co-chair. And I had Barry Goldwater on the same stage with Jane Fonda. I loved that.

It seems that, despite all the progress we’ve made since Maude left the air, the country also seems more conservative than it was back then. Maybe even more divided — and things were pretty divided in the ’70s. Does this surprise you?

It is very troubling. And I have another way of thinking about it — but your thumb is on the same button. When I came out of World War II, we were in love with America. We were in love with the idea of America. There were civics classes in our school, and we learned about the First Amendment, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights in school. We saluted the flag in a lot of classrooms every morning. The way I view it is: We were in love with America. I’m not questioning anyone’s patriotism today — we love our country. But the in love factor doesn’t exist, as I see it.

Leadership everywhere is out to lunch. Eisenhower left office warning us about the military industrial — in his first draft, he called it “the military-industrial congressional complex.” He was saying the country could be owned by that complex. [And] I think it’s eating us alive. It is in control, and it’s hard to be in love with the America we were in love with. Nobody’s talking to [us] about the things that protect us. They’re only behaving like everybody has everything they need. Like we delivered on the promises. The fact is, we haven’t yet delivered on the promises. As you look at what’s going on now with Ferguson, and immigration — it’s so clear in the broadest way, in every area you look … we’re being lied to by corporations, by companies that own prisons, by Congress itself.

I kind of took us down a different road.

I didn’t expect this conversation to take this turn!

We can get back to TV. Maude is now out on DVD, and many of your shows are out on DVD — but not all of them. Would you like to see all of your series available for streaming? Would you like to see a day where anyone could go online and see all of your library?

I would love that. Including some of the shows that didn’t work. Or a couple of the shows that I thought worked but didn’t rate well enough for the network to hold onto.

Such as?

All That Glitters. That was five times a week like Mary Hartman. Fernwood 2 Night, you probably remember. It followed Mary Hartman, with [Martin] Mull and Fred Willard, which was funny as anything. I mean, God, I loved it.

Do you have the rights to all of your shows still?

No, it’s all Sony. But my relationship with Sony is excellent.

Have there been any conversations with Sony about putting all of the shows online for streaming?

I’ve not had those conversations, but there could good be a network for those shows. All of them but Hot L Baltimore. Oh my God.

There have been reports of Sony coming to you about an All in the Family remake. And I know Sony is working on a Latino One Day at a Time. Any updates on these?

We’re thinking about that. I wouldn’t think, by the way, of ever doing All in the Family with the Bunkers. It would be the use of the title in a different family, so it would be All in the Family 2016.

One show of yours I’ve thought could easily be updated is Good Times.

Oh, I love Good Times.

That show had some of the fiercest behind-the-scenes battles with the cast, or at least that’s how it’s seemed based on reports from the time. You had both of your leads leave the show at one point or another.

Those were all very understandable. Just imagine this: There are no African-American families on television. Suddenly, you — Esther Rolle and John Amos — represent the first African-American couple with children on American television. You are the TV role models of your community’s people. That’s heavy responsibility. I’m not sure at the time I understood this as well as I understood it some years later. But I kind of understood the heaviness — the weight on them.

There was an episode with Thelma that they didn’t like.

I wanted to do a show about Thelma, the daughter, who was 16. Boys [were] pushing at her, you know — sex. And I wanted to open that up in the family, and they don’t want to do that. It wasn’t like I didn’t understand that it was coming from a good place. But some decisions had to be made that wouldn’t be popular with those actors, and I had to make a couple of those decisions. I mean, we did do that episode. There was no intention of Thelma going to bed with anybody. We would never think about that. But talking about the problem was something we could do, and did do. And that wasn’t welcome, but we did it. And we got through it.

Have you seen any of the new comedies this season which have explored race?

I have seen Fresh Off the Boat, yeah. I thought it was good.

You must get asked a lot for your opinions of shows.

I simply don’t have time to watch everything. You know, there are so many shows that people — people I respect and care for — say, “Are you kidding, you haven’t seen Empire?” I just haven’t.

Final question: In one sentence, could you say what you would like your legacy to be?

[He was] somebody who helped everybody understand how much each of us matters.