This piece contains spoilers for the season-three finale of The Americans.

Confessions have been a persistent motif throughout The Americans this season, and in the final episodes, they came flooding out. Philip removes his wig and stands as a stranger in front of Martha. Stan, somewhat giddily, informs his boss that not only had he been carrying on with an asset, Nina, but that he was conspiring with a KGB rival to guarantee her safe return. Paige, crying in her bedroom, calls Pastor Tim in hope of consolation. “They’re not Americans,” she says through tears. “They’re Russians.”

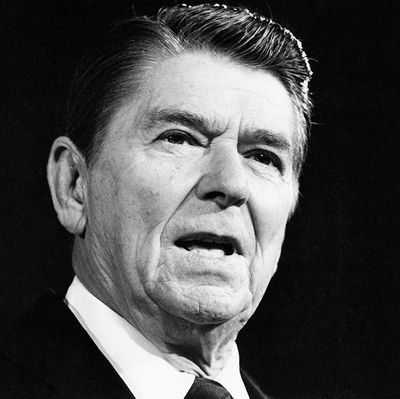

And then there’s Philip, whose season-long internal doubts finally come to a head in the finale, titled “March 8, 1983.” Just as he’s struggling to verbalize his disillusionment to his wife, Elizabeth becomes distracted by the nightly news. “Hold on, we should listen to this,” she says. And so the closing words of season three instead go to Ronald Reagan, who, in his March 8, 1983 speech to the National Association of Evangelicals, brands the Soviets as “the focus of evil in the modern world.” In the address, Reagan attempts to steer Americans away from the nuclear freeze movement and convince them of the righteousness of his nuclear rearmament strategy in response to the Soviet Union’s own military ambitions. Reagan’s words are at once defiant and confessional. His voice projects confidence, but also the message: “I know I’m not supposed to say this, but here’s what I’d like to get off my chest …”

High politics took a backseat in season three, which covered the period from Soviet Union leader Leonid Brezhnev’s death in November 1982 to Reagan’s “Evil Empire” speech on March 8, 1983. Closing with the Gipper suggests we can expect more interaction next season between the main characters and the headlines. 1983 was one of the tensest years of the entire Cold War, and Reagan’s words accentuated that tension. Americans were on edge about nuclear war, and felt uneasy about Reagan’s rhetoric in his negotiations with the Soviets. That November, an estimated 100 million people tuned in to ABC to watch The Day After, which depicted a nuclear attack on Lawrence, Kansas, prompting the White House to send Secretary of State George Shultz to appear on the network immediately following the television movie in an attempt to reassure distraught viewers.

Soviet leaders, meanwhile, brushed aside Reagan’s use of “evil” as nothing new. They had more immediate concerns about a speech he gave a few weeks later, on March 23, when the president announced the Strategic Defense Initiative (“Star Wars”), whereby the United States would build a shield in space that would someday “render nuclear weapons impotent and obsolete” (recall that in season one of The Americans, Philip and Elizabeth went to considerable lengths to obtain the administration’s plans to build a ballistic missile defense). They focused also on NATO’s scheduled deployment of a new generation of nuclear missiles in Western Europe, as well as U.S. pursuit of stealth technology (another recurring plotline on The Americans).

Tensions didn’t peak, however, until September 1, 1983, when Soviet fighters shot down a Korean civilian airliner, KAL 007, killing 269 passengers and crew. The Reagan administration took a harsh rhetorical stance and introduced measures to rein in the Soviet Union. KGB operatives were instructed to watch and listen carefully for any signs that Reagan was planning to launch a preemptive nuclear war. In London, a Soviet double agent named Oleg Gordievsky informed his handlers in British intelligence about chatter that NATO’s military exercise, “Able-Archer 83,” was in fact a prelude to the real thing. We can certainly expect to hear more about these events in season four — and perhaps witness Philip, now wavering in his commitment to the cause, following Gordievsky’s example.

But it was people like Paige — not the Russians — whom Reagan intended to reach on March 8, 1983. Reagan’s speech carries powerful religious undertones. It begins with a direct appeal to his audience: “Those of you in the National Association of Evangelicals are known for your spiritual and humanitarian work, and I would be especially remiss if I didn’t discharge right now a personal debt of gratitude.” The president proceeds to weave religious and moral language throughout: “Freedom prospers when religion is vibrant, and the rule of law under God is acknowledged”; “let our children pray.”

The purpose of the March 8, 1983 speech was to appeal to people of faith who were inclined to follow the National Conference of Catholic Bishops in support of the nuclear freeze movement. This is the season Paige asked to be baptized and turned to Pastor Tim as her guiding light. Where does she go now? She could become a poster child for the nuclear freeze movement in the model of the real-life Samantha Smith, the all-American girl who wrote letters to Soviet General Secretary Yuri Andropov and visited the Soviet Union. That certainly seems to be what Pastor Tim has in mind. But if Reagan’s words reach her as he hoped they might, we could see Paige rallying for his reelection. Paige is part of the broader audience Reagan was aiming to reach, at a time when his own daughter, Patti Davis, was speaking at anti-nuclear protests and bringing anti-nuclear activist Helen Caldicott in to the White House to meet with the president.

My vote is for Paige to wind up onstage at the 1984 Republican National Convention singing along to Lee Greenwood’s “Proud to Be an American.” It would be the ultimate act of teenage rebellion.

James Graham Wilson is a historian at the U.S. Department of State. He is the author of The Triumph of Improvisation: Gorbachev’s Adaptability, Reagan’s Engagement, and the End of the Cold War. The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of State.