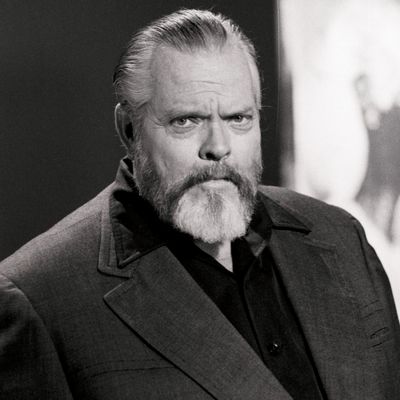

Josh Karp’s riveting, wildly entertaining new book Orson Welles’s Last Movie follows the ill-fated production (and endless postproduction) of The Other Side of the Wind, one of several films the legendary director left unfinished at the time of his death in 1985. The insanely ambitious project was filmed over many years and different locations, often in bits and pieces. Over the years, it has gained mythical status — a film that is almost fully shot, but whose completion remains out of reach due to a whole variety of complicated circumstances. In honor of what would be Welles’s 100th birthday, here are 19 things we learned about the film.

1. The movie would be a highly stylized, self-reflective combination of classic and modern. Not unlike Citizen Kane, the film would begin with the death of the main character as Welles’s voice narrated over “the mangled, smoking remains of a sports car.” The film would then flash back to tell the story of Jake Hannaford, a legendary filmmaker from Hollywood’s Golden Age who feels out of step with the times. Like Welles himself, Hannaford is returning from an extended stay in Europe, and attempting to make a film that will resonate with the youth culture of the 1960s. Much of Welles’s film would contain Hannaford’s film, but it would also tell the story of the director’s last day, as he attends a 70th birthday party peopled with all manner of friends, associates, hangers-on, and sycophants. Meanwhile, documentary crews follow Hannaford throughout. Welles’s finished film, thus, would be a dizzying combination of all different kinds of footage, film stock, and shooting techniques. (Ironically enough, the film Hannaford is working on, also called The Other Side of the Wind, would also be left unfinished in Welles’s movie.)

2. The main character was based on a number of real-life people. Maybe. Though it seems at least somewhat autobiographical, the character of Jake Hannaford was based partly on Ernest Hemingway — whom Orson Welles first met when the writer tried to punch him out in the sound-recording booth where they were working on the voice-over for the famous 1937 documentary The Spanish Earth. Later, Welles would tell others that Hannaford was modeled after “hypermanly filmmakers” like John Ford, Henry Hathaway, Howard Hawks, John Huston, and Rex Ingram. To his eventual star John Huston, he would simply say, “It’s about us, John.”

3. Welles also took a dig at Antonioni. The idea of a director attempting to make an arty, pretentious movie about youth culture was based partly on director Michelangelo Antonioni, whom Welles hated, and his famous flop, Zabriskie Point.

4. Cold-calling Welles at the right moment could work wonders. In 1970, cameraman Gary Graver, then a relative unknown whose previous credits included films like Satan’s Sadists and The Girls From Thunder Strip, blindly called Welles at the Beverly Hills Hotel (on a hunch) and nervously offered his services to the director, whom he had just read was preparing to start a new film. Welles hired him that day, saying, “You are the second cameraman to ever call me up and say you wanted to work with me. First there was Gregg Toland, who shot Citizen Kane. Since then no technician has ever called me up and said they wanted to work with me. So it seems like pretty good luck.” Graver would not only shoot Wind, he would also become one of Welles’s closest collaborators for the remainder of his life.

5. Graver got Welles to help with a porno. Graver regularly shot erotic films under a pseudonym. One day in 1975, Welles called him urgently to his side, while Graver was finishing up a soft-core flick called 3 A.M. When Graver refused to leave due to his prior commitment, Welles agreed to help Graver finish the film. Therefore, Orson Welles “allegedly wound up editing a hard-core lesbian shower scene that he couldn’t resist cutting in Wellesian fashion with low camera angles and other trademark flair.”

6. Orson Welles’s relationships with women were even more complicated than we thought. Welles’s other key collaborator was his mistress Oja Kodar, a Croatian model and actress whom he had been with since the 1960s, and who would remain by his side until his death. (She played a major role in his 1974 film F for Fake, one of his greatest works.) At the same time, however, Welles continued to be married to his third wife, Paola Mori. As Karp writes, “Welles … found himself maintaining two separate lives over the next twenty years: a bohemian existence with Oja in Los Angeles, Paris, and Spain; and a more formal arrangement with Paola and Beatrice [his daughter] in London and later Sodona, Arizona, and Las Vegas. And because he was accustomed to managing chaos, he supposedly kept Paola from even knowing about his relationship with Oja until a year before his death.”

7. For much of the shoot, Welles didn’t know who would play the lead. Welles hadn’t decided on who would play Hannaford at first, so he shot a lot of scenes in which he himself stood in for the protagonist off-camera, with the plan of shooting the lead actor once he’d been cast. Eventually, he would cast John Huston — one of the models for the character. By the time Huston started, some actors had been working on the film for three years — a fact which stunned the veteran director.

8. Many of the characters were based on real-life people. Welles cast his protégé Peter Bogdanovich as a “smarmy” critic modeled after Rex Reed and Charles Higham, while the critic Joseph McBride was cast as a hyperintellectual film writer. Welles cast Susan Strasberg, daughter of the infamous acting teacher Lee Strasberg, as “the bitchy, pretentious critic Juliette Riche,” who was modeled after Pauline Kael, who had just published the controversial Citizen Kane Book, challenging Welles’s role in the authorship of his most beloved film. A character named “The Baron” was based on John Houseman, Welles’s longtime Mercury Theater partner and producer on Citizen Kane. Another character was modeled after the right-wing, man’s-man action director John Milius. Yet another was based on then-Paramount executive Robert Evans, producer of Chinatown.

9. While Peter Bogdanovich played someone else, Rich Little played Bogdanovich. Comedian Rich Little was cast as Brooks Otterlake, a protégé of Hannaford’s who wants to write a book about him but gets sidelined with his own successful directing career — a part modeled after Bogdanovich. After Little suddenly left the film mid-shoot, Welles had to recast the part — so he got Bogdanovich himself to do it, even though the young filmmaker was already playing a different, smaller role in the film. Always fond of a perverse gesture, Orson Welles also hired Polly Platt, Bogdanovich’s estranged wife and costume designer, whom the young director was in the process of leaving for Cybill Shepherd, his lead actress from The Last Picture Show.

10. Lucasfilm head Frank Marshall was the line producer. Platt brought along with her Frank Marshall, the production manager on The Last Picture Show, who would serve as Welles’s line producer and would later go on to produce Raiders of the Lost Ark, Back to the Future, and is now the co-chair of Lucasfilm. The mercurial Welles would often fire Marshall, but the loyal Marshall would never actually leave, because he knew the director needed him. Welles would assume Marshall had returned to Hollywood, but “each time,” Karp writes, “the line producer would go to the Desert Forest Motel, get on the phone, and talk someone through his job until Orson summoned him back.”

11. Managing this shoot was impossible. Welles started shooting at his rented house in Los Angeles, but he shot scenes all over town and on the MGM back lot. By making his crew pretend to be UCLA film students, the production could rent the lot at $200 a day, as long as Welles himself hid when they passed through the gate at the front of the studio. Later, the production moved for an extended shoot to Carefree, Arizona, where Welles had rented a home under the pretense of working on his memoirs. There, a neighbor became convinced there was a porno shoot going on, having seen the blacked-out windows and all the young cast and crew coming in and out, and called the police on the filmmakers.

12. John Huston. Just … John Huston. Though Huston was himself an accomplished actor, Welles cast him more for what he represented than for his specific acting abilities — and he often didn’t care that Huston couldn’t memorize his lines. When he forgot his lines, Huston would often “just say something — anything — with enormous authority and confidently exit the scene.” Also: One night, for a scene in which Hannaford drives to a party, Welles and several cast and crew piled into a car and let Huston drive the car in character. Unfortunately, Huston had stopped driving decades ago, after concluding “that drinking and driving didn’t mix and decid[ing] to make a choice of one or the other. Drinking won.” He immediately clipped a tree and hopped a curb, almost killing Bogdanovich, who was in the passenger-side seat. Welles let Huston continue driving, however. So Huston went “the wrong way down an exit ramp and into high-speed traffic on an expressway … [w]ith everyone screaming and the cameras rolling.”

13. Those working on the shoot were in awe of Welles’s ability to direct. “Welles would stalk around the set, look through a circle he made with his fingers, and explain precisely which lens and focal length were required. Without looking through the camera, he always knew exactly what image would be captured if its operator followed his instructions … Then there was his conceptual ability, as he seemed to be creating each frame as if it were its own work of art and then — in his head — weaving them together into a creative whole that exceeded the sum of its parts.”

14. The Iranian Government did not seize the film’s negatives — though they did try. Money problems hounded the shoot, and Welles had forged a complicated alliance of financiers for the film, one of which was Mehdi Bushehri, brother-in-law to the then-Shah of Iran. Through his company Astrophore, Bushehri wanted to promote Iran as both a location for outside productions as well as a co-financing partner with established filmmakers. (He would eventually sink more than $1 million into the production.) Years later, in the wake of Ayatollah Khomeini’s Islamic revolution, the Iranian government attempted to seize control of the Paris-based Astrophore and the film’s negative as “the property of the Iranian people.” But Bushehri, the film’s Iranian financier, had at the last second promoted one of his French employees to managing director of his company, thus muddying the issue of ownership. More important, however, Astrophore had just been hit by an erroneous tax bill by the French government for $600,000. When the Iranians actually showed up to seize the company (and the film’s negative), they were immediately presented with the huge tax bill, which was due in three days. The Iranians gave up on acquiring the company, and the film did not fall into the hands of the Khomeini regime, as had once been feared.

15. Welles was a brilliant editor. Welles edited the film all over the place, including France, Rome, and Bogdanovich’s Los Angeles mansion, where he also continued to shoot some scenes. His editor in France, Yves Deschamps, felt that “Welles was the greatest editor that he’d ever meet … As they worked, Welles was like a dancing symphony conductor. With his imagination fired up, he underwent a physical transformation. Gone was the heavy breathing and constant pain. Once he was rolling, Orson would float around the room with fluidity and grace, moving from one editing machine to the next and telling each editor to cut here or mark there.”

16. Hollywood was unwilling to help Welles, even as it bestowed awards on him. When he was given the 1975 AFI Lifetime Achievement Award at a star-studded ceremony, Welles showed an assembly of clips from The Other Side of the Wind in an attempt to get more financial backing for the film. Nobody in Hollywood came to his aid.

17. After Welles’s death in 1985, his associates tried to get numerous big-name filmmakers to finish editing the film. John Huston, himself frail and elderly, looked at some of the footage but decided he wouldn’t know what to do with it; instead, he suggested his son, Danny, but that deal fell through when a gossip column ran a news item about it immediately following the meeting. Oliver Stone, George Lucas, and Steven Spielberg were all approached, and declined the offer. Clint Eastwood showed interest, right before he departed for Africa to play John Huston in White Hunter, Black Heart. When that film flopped, however, Eastwood found his clout reduced and was unable to pursue the project.

18. Even throwing a ton of money at the problem didn’t seem to bring the film closer to completion. At one point, Mississippi Burning producer Fred Zollo came very close to buying all the rights to the film and finishing it, even offering all the various financial parties involved a few million dollars each to let him buy them out. But the more he offered, the more they asked for, and he eventually “decided the situation was too ridiculous even for Hollywood and walked away.”

19. Will it ever see the light of day? The impending completion of The Other Side of the Wind has been announced numerous times — most recently, in 2014, with Frank Marshall’s involvement. Up until now, finishing the film has been derailed by a tangle of competing interests, including Oja Kodar, Beatrice Welles (Orson’s daughter), as well as others who’ve claimed part ownership of the film. The project came very close in 1998, when Showtime got involved and agreed to hire Bogdanovich to oversee the final edit and postproduction, but even that fell apart. Karp quotes Showtime executive Matthew Duda, who tried to shepherd the project to conclusion: “Just when you thought you’d made some progress, there was always something and you’d slog back … The personal stuff ebbs and flows over the years. Everybody loves everyone, then they hate each other. They work together and then they won’t work together.”