Dear Hollywood,

As Vulture’s resident comma queen, my job is to make sure our writers mind their p’s and q’s and em dashes. While I mostly edit for clarity, accuracy, and house style, lately I’ve been fielding excessive questions regarding movie titles of unwieldy length, and the mechanics that make them manageable. Or, in the case of this weekend’s Mission: Impossible — Rogue Nation, attempt to do so.

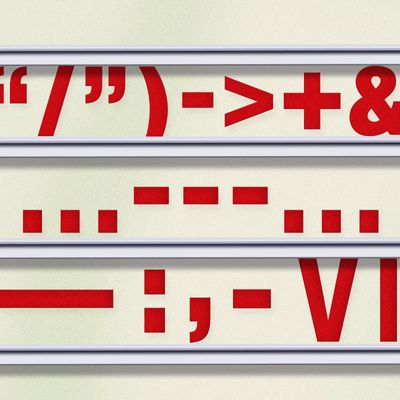

It’s been a banner year for punctuation on multiplex marquees, and we copy editors have had to brush up on our HTML as a result. New York’s house style requires that we use films’ official IMDb titles on first mention, which is how we wind up with marked-up monstrosities like The Divergent Series: Insurgent. There was a time when colons and dashes served a practical purpose: to convey a hierarchy of loosely connected ideas of descending importance. But like any trendy accessory, these structural tools are dangerously approaching overuse.

Historically, franchises are to blame. It’s hardly a new problem — while Star Wars: Episode V — The Empire Strikes Back is an undeniable classic, its title’s structure merits less praise. But as Hollywood continues to lean on its established properties, film-title typists are involving the “shift” key with more regularity. The Hunger Games team, for one, seems to have little faith in its audience’s ability to recognize each installment as a cog in one machine. Slapping a Catching Fire at the end of the title is obvious, but as run times increase, we end up with convoluted titles like The Hunger Games: Mockingjay — Part 2 in order to cram ever more information onto each poster.

Perhaps no series has taken a more unfortunate grammatical turn than the increasingly impossible Missions. The colon in Mission: Impossible was initially stylistic, a much more defensible and even enjoyable flourish when the movies simply ended with numbers. Then the franchise’s fourth and fifth installments elected to tack vague qualifiers onto the original title, Hunger Games–style, turning the stark graphic quality of Mission: Impossible into just another punctuational nuisance. One finds herself wishing M:I’s sequel-namers were as agile as Ethan Hunt.

But franchises, by virtue of being iteration-oriented, at least have an excuse. What about the movies whose convoluted structures stuffed with superfluous punctuation appear for no reason at all? Are the latter two marks in Crazy, Stupid, Love. — that second comma and a particularly galling period — proof that love is illiterate as well as blind? Which came first: the parentheses in (500) Days of Summer, or its poster’s graphic-design concept? Why does the colon in Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb follow the “or:” instead of preceding it? Does Airplane! conclude with an exclamation mark to cement its status as the greatest and most ridiculous satire ever, full stop? (Yes.) Bonus round: Is Sex&Drugs&Rock&Roll the name of a TV show, or the latest take on those parody Beatles band T-shirts?

Perhaps worse are films whose titles incorporate some punctuation, but not enough. In O Brother, Where Art Thou?, what exactly is an “O Brother”? (I don’t care about the original text upon which it was based; we know better now.) Listen Up Philip: How can you expect Philip to listen up when he can’t parse his title? Why is Who Framed Roger Rabbit declarative.

It doesn’t have to be this way. Legions of fans follow James Bond’s exploits despite each installment’s unique title, from Dr. No to Spectre and all 22 007 films in between. Sure, Bond flicks tend to reinvent themselves in a way that, say, the Harry Potter series never did, but its diverse nomenclature serves as a reminder that the moviegoing public will show up no matter what is printed on their tickets, so long as there’s enough recognizable action packed into the marketing materials.

Major studios would also be smart to follow Die Hard’s lead; the second film in the series is the only one that takes a number, while subsequent additions to the franchise put their own spin on the initial property with a vengeance, so to speak. Or perhaps franchises could take a cue from The Fast and the Furious. I’m no good at counting, so I’ll take Tokyo Drift in place of a number any day; and leading with the number à la 2 Fast 2 Furious is about as brilliant as tentpole-titling gets. (Honorable mention: inter-title numbering, such as the third Taken film’s unofficial name.)

In this humble copy editor’s opinion, a title should tell the viewer what’s in store for her, not introduce a new question. Each distinct movie should provide a unique experience; studios should trust that their public is clued in enough to know how to follow a franchise without an unending echo. Sure, it’s hard for new releases to stand out in a crowded cinematic landscape, but a concise title helps convey strength and authority. I’d much rather shell out 15 bucks for a film with a bold title than one that looks like a marked-up term paper.

Remember, studios: You need a colon to survive, but any more than one and you’ll have a mess to clean up. And a dash in a title does not inspire a dash to the theater.

With marked love,

Lauren Leibowitz