On June 26, Comedy Central began streaming every single episode of The Daily Show under Jon Stewart’s tenure, an event it deemed the Month of Zen: an uninterrupted deluge of satirical news running 24/7 for more than a month. In that time, I managed to catch 100 episodes of Stewart’s nearly 17 years as host, charting its rapid maturation from unfocused finger-pointing into the lean, mean satire machine it is today.

1999

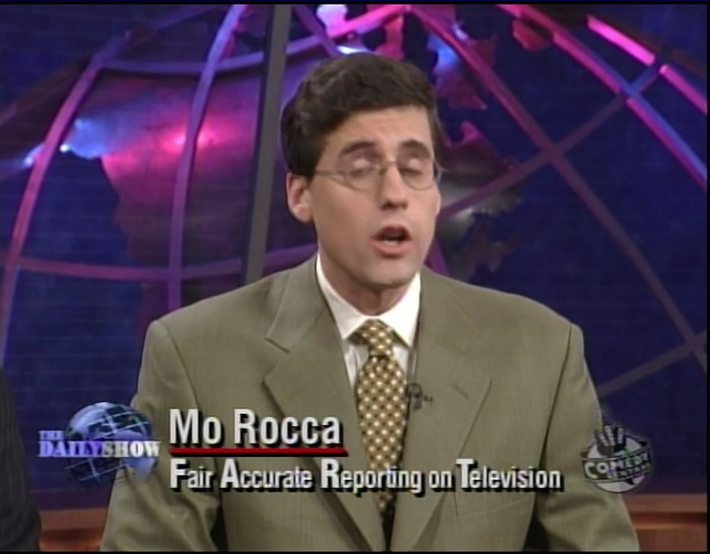

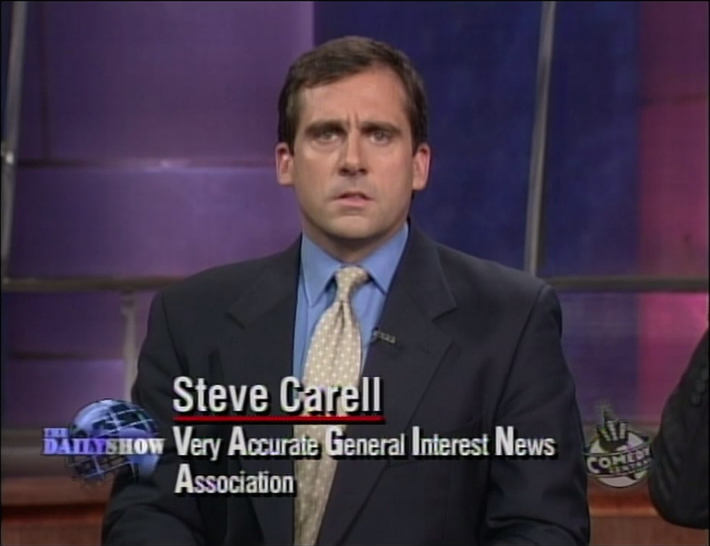

I first opened the stream at 1:12 p.m. on June 28, during an episode from its first season, on September 30, 1999. The show was in the midst of a segment making fun of Garth Brooks’s ill-fated journey into rock music under the pseudonym of Chris Gaines. As dated as that segment was, the early episode then transitioned into what would become the program’s calling card: a segment on media responsibility. Three correspondents — Vance DeGeneres, Mo Rocca, and some guy named Steve Carell — were all setting up media-watchdog organizations. DeGeneres introduced News Activism Means Better Living for All (N.A.M.B.L.A.), Rocca founded Fair and Accurate Reporting on Television (F.A.R.T.), and Carell conjured up the Very Accurate General Interest News Association (V.A.G.I.N.A.). This was the state of The Daily Show’s media criticism in 1999: pedophilia, fart, and vagina jokes. Funny? Yes. Trenchant? Not quite.

These nascent episodes of The Daily Show, viewed in hindsight, have an odd whiplash effect, moving back and forth between amusingly outdated segments and universally relevant ones. For instance, in that September 30, 1999 episode, Stewart expressed skepticism towards Jeff Bezos’s claim that “Amazon.com will be a place where you can find and discover anything.”

Two days later, on October 7, 1999, Stewart was covering Donald Trump’s decision to enter the 2000 presidential race. The more things change, the more they stay the same.

There are also some artifacts best left in the ’90s. One particularly odious field report from Mo Rocca focused on Ara Tripp, a transgender woman:

It hinged on the repeated phrase “tower-climbing, fire-breathing, topless transsexuals” as a punch line.

2000

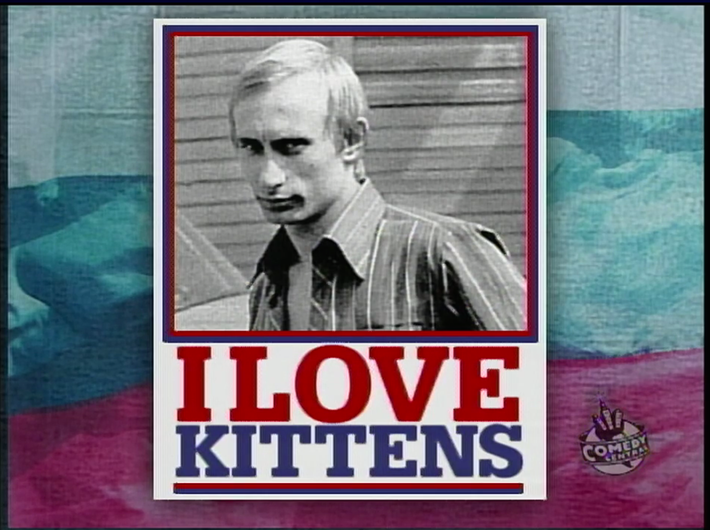

By the evening of June 29, the Month of Zen stream had moved into the current millennium. It was late March 2000: Pope John Paul II was visiting Israel, providing an excuse, for the first time since I had started watching the stream, for Stewart to trot out his trademark Jewish accent. Elsewhere, Hilary Swank forgot to thank her husband during her Oscar speech, and a small Cuban boy named Elian Gonzalez was the subject of an international custody battle. In a special-edition segment of Indecision-sky 2000-slav, a former KGB agent named Vladimir Putin was running for president of Russia.

It’s worth pausing here to examine just what Stewart’s role is in all of this. In hindsight, the early Daily Show seems like a fairly rote satirical newscast, heavily segmented with recurring bits. Stewart begins the episodes running through “Headlines,” “Other News,” and “This Just In,” and then recapping all of the episode’s topics at the end with a send-off joke. Though clearly liberal, Stewart never takes much of a stance on anything, other than “[Insert topic] is ridiculous,” and he plays the straight man to far more animated correspondents like Carell, Stephen Colbert, and Nancy Walls.

Stewart’s oft-repeated analogy is that he’s not political but instead at the back of the class shooting spitballs at targets deserving of ridicule. That positioning soon became irrelevant, but at the start of Stewart’s tenure, it was very true. At the top of every episode, the show introduced itself as “The Most Important Television Program … Ever,” a designation that worked precisely because, well, it was far from it.

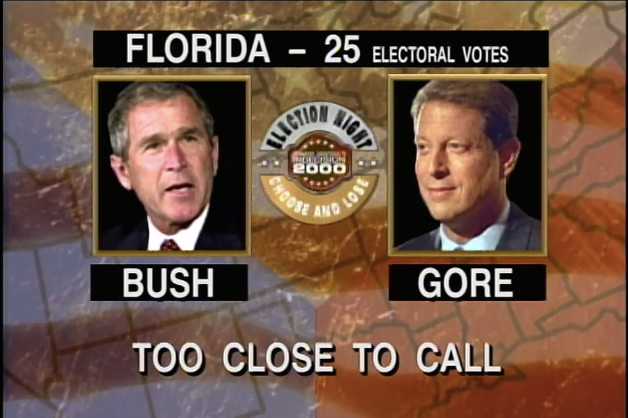

Bet then came November 7, 2000, Bush versus Gore, and Indecision 2000. “It is too close to tell, and I just don’t know what to do,” Stewart says towards the end of the broadcast, which also featured a segment in which Lewis Black made fun of Bush’s articulateness, or lack thereof. Viewers were also invited to head over to news.yahoo.com and take a poll.

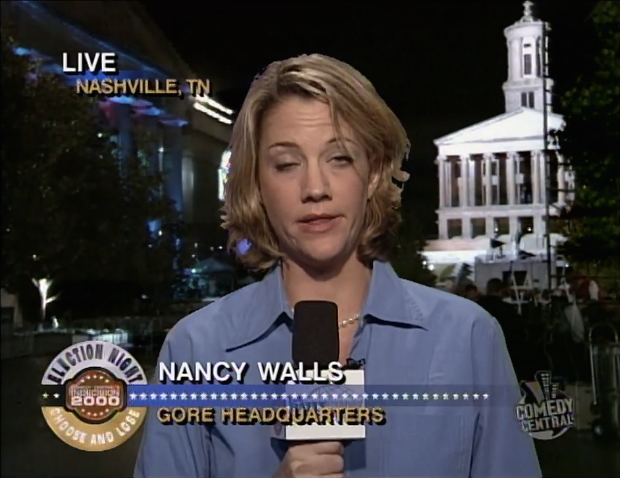

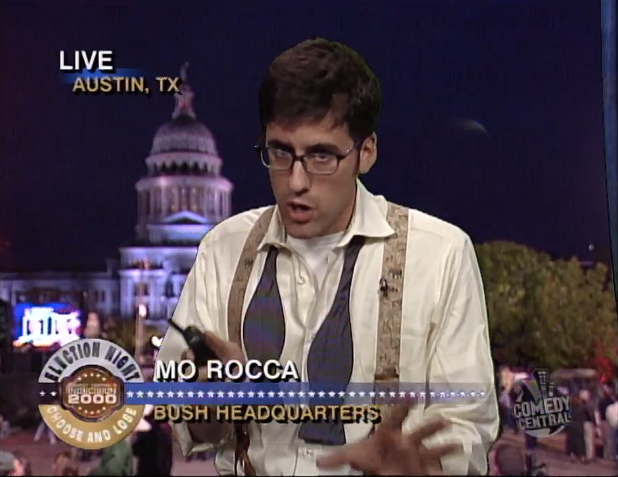

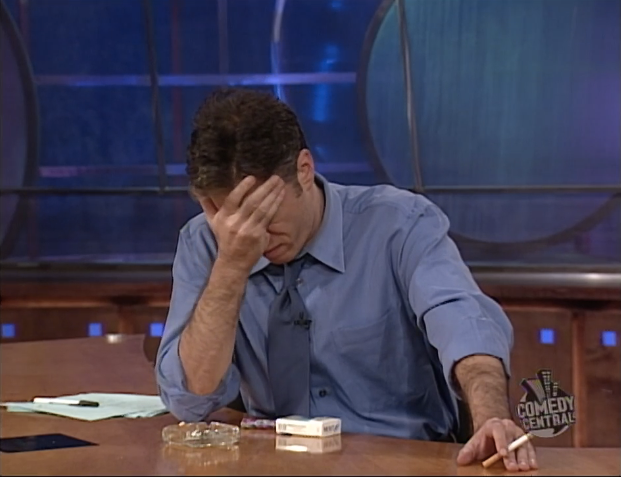

The show returned the next day with the election still undecided, a bigger fiasco than any of them could have anticipated. “Calling this thing Indecision 2000 was at first a bit of a lighthearted jab,” Stewart says at the top of the broadcast. The entire team acted as if they had been trapped in the studio all day, waiting for the election to be called: Stewart chain-smoking at his desk, Walls and Rocca looking delirious “outside” the Gore and Bush headquarters, and a harried Colbert trapped in a decisionless purgatory.

Closing out the show, Stewart signs off, “Good-night, and help us.”

With the election undecided, the show focused on other topics. Pets.com goes under in mid-November, and in an odd bit of promotion, the show devotes an entire week to interviewing the cast of Little Nicky.

But there’s still a lot to be mined from the situation in “big ol’ retarded Florida.” Colbert heads up a panel of old, indecisive Jews and Stewart interviews “the world’s foremost authority in mathematics,” Sesame Street’s Count (a sort of precursor to the show’s recurring “Gitmo” segment, consisting of a puppet-resembling Elmo). Stewart also takes time to speak with tireless legal expert Greta Van Susteren, who was working for CNN in 2000 as, in Stewart’s words, “a voice of reason” amid partisan commentators.

The show’s 2000 election coverage is the first hint of the type of righteous indignation that Stewart would eventually become famous for. “The final margin in the state of Florida: 5 votes to 4 votes,” Stewart says of the Supreme Court decision, adding that, with the support of Clarence Thomas, Bush won “100 percent of the African-American vote.”

2001

At this point, the Month of Zen stream had been covering Indecision 2000 for eight hours, and I decided to take a slight break during the first half of 2001, knowing that the show was nine months out from … you know. Most of the show’s presidential commentary during the early 2001 period focused on Bush’s ability to conjure up new words and speculation that Cheney was pulling the strings, a joke that was old even in 2001.

By the morning of July 3, the stream had edged up to August 2001. Vance DeGeneres had left the show, and at some point, Matt Walsh (sans mustache) joined. The nation’s teenagers were injuring themselves trying to imitate Jackass, and Kevin Smith and Will Ferrell dropped by to promote Jay and Silent Bob Strike Back.

On August 23, 2001, the show signed off and took a two-week break. It returned on September 10, 2001.

There’s not much notable about the show’s last pre-9/11 episode, other than an ominous feeling that exists only because I knew what was next. They Might Be Giants were on to promote “Mink Car.” The show’s Moment of Zen was of Bush performing a terrible coin-toss.

The show ceased production after 9/11 and returned on September 20. That first episode following the tragedy rolled in without an intro, without Bob Mould’s theme song, and without an announcer stating the date of the broadcast. It just faded up on Jon Stewart’s now-famous shaken monologue. “Our show has changed,” Stewart says. “What’s it’s become, I don’t know … ‘Subliminable’ is not a punch line anymore.”

The show’s Moment of Zen is Stewart reaching under his desk and pulling out a puppy.

There are a number of visible changes that appear over the course of the week. For one, the show’s intro and outro music is acoustic, a conscious choice to put the audience at ease. Stewart’s first three guests are all journalists: Frank Rich, CNN reporter Aaron Brown (who at that point was still tirelessly anchoring the network’s coverage), and Jeff Greenfield. Up until this point, Stewart’s guest roster had been almost exclusively composed of Hollywood celebrities. Following 9/11, there’s an obvious broadening of guests on the show. Though still dominated by celebrities, there’s a conscious effort to include more journalists, and Stewart, even at this early point in his career, is great at asking questions on behalf of his audience and admitting that he doesn’t know what he doesn’t know. On October 18, 2001, Fareed Zakaria made the first of what would be many appearances on the show, discussing his Newsweek cover story, “Why They Hate Us.”

Which is not to say that Stewart’s show became deadly serious. On his third show back from the tragedy, September 25, 2001, Stewart and Colbert ridiculed the latest early ’00s Fox reality nightmare: the prime-time special Who Wants to Be a Princess. By September 27, the standard date announcement intro had returned, but without the proclamation of The Daily Show being “The Most Important Television Program … Ever.”

2002

On July 5, the stream had reached June 2002. Some new faces, Ed Helms and Rob Corddry, had joined the cast. A particularly exceptional Even Stevphen segment from June 19, 2002 begins with a debate on the so-called “death tax” and ends with Carell and Colbert negotiating a hit job:

The summer of 2002 also featured the first I had yet seen of what would later become a Daily Show trademark: a series of clips in which the subject of ridicule digs his own grave. In this case, it was just-expelled Ohio congressman James Traficant. It was around this time that The Daily Show team seemed to be sharpening its research and compilation skills.

When I picked up the stream again, it was the fall of 2002, WMD inspections in Iraq were dominating headlines, as well as a certain windsailing senator. On a November 12, 2002 episode, a week after the midterm elections, Stewart noted: “One beacon of hope is potential democratic president John Kerry.”

2003

The episodes of early 2003 find The Daily Show crystallizing the political identity that it showed briefly post–Election 2000 and more frequently post-9/11. The show knows when to poke fun at the ridiculousness of the situation, like when Republicans wanted to shift from French fries to “freedom fries.” But Stewart’s interviews – an aspect of Stewart’s showmanship that has been exceptional since the beginning – show a host perfecting a style both genial and confrontational. When he interviews Dick Gephardt just over a week before “shock and awe” began, Gephardt at one point voices the oft-repeated idea that Bush is “a uniter, not a divider.” Stewart forcefully but slyly replies, “Europe is pretty united right now.”

The shows immediately preceding the start of the War in Iraq positions Stewart as an almost calming presence amid the uncertainty of a military operation far more dubious than the one in Afghanistan. On March 17, 2003, Stewart leads off his show by telling viewers, “This show is taped, so as far as I know, right now, we are not at war,” advising them to “check the other live stations right now.” On March 20, the day the war commenced, Stewart simply promised to “keep you informed of any late-breaking humor.”

The day that the Iraq War began, Stewart rolled out a perennial favorite: Fox News criticism, sarcastically referring to them as, “Fair. Balanced. AWESOME!”

Perhaps most telling in all of this is that, by March of 2003, the audience response to Stewart’s jokes has changed. More than ever before, Stewart’s quips about the shakiness of the case for war in Iraq are met with claps of agreement, not laughs. The week following the start of the war, in a segment examining Dick Cheney’s close ties to Halliburton, Stewart at one point remarks: “Hearing that does make me feel like the government just took a shit on my chest.” That’s not really a joke, is it?

Stewart solidified his place in the national consciousness not by making his audience laugh but by voicing concerns they agreed with. By early 2003, Stewart had seen egregious politicking (the Supreme Court handing the 2000 election to Bush), staggering, era-defining tragedy (the 9/11 attacks, from New York City), and watched as the executive branch launched a widely criticized military operation (Iraq). For Stewart to stick to spitballs from the back of the class, and not become a liberal advocate of sorts, seems nearly impossible. But Stewart framed his arguments not as a liberal TV host speaking against a conservative government (and 24-hour news channel), but as a rational TV host against irrational foes.

2004

The Daily Show had so solidified its political and cultural voice that by 2004, the Month of Zen stream had become less interesting to watch. It was fascinating to see Stewart come into his own (and somewhere along the way acquire a suit that actually fit him). The rest of it — with still more than a decade to go — became less about watching the show develop and more about appreciating how it maintained such a high plateau.

Stewart himself references this in a late October 2004 episode, just before the election. Leading off the show, he remarks that that night’s episode was, “Bush said this, Kerry said this, Lewis Black is angry.” Stewart seems to already be feeling a slight malaise on November 1, 2004, when he asks voters to “make these next four years difficult for me” by electing Kerry into office, ostensibly robbing the show of its main villain, the Bush administration.

The next night, Election Night 2004: Prelude to a Recount, Colbert kept an abundance of survival supplies near his desk. Ed Helms declared Bush an early winner without having official results: “Waiting for official results is a sign of weakness.” And in case you thought the show had outgrown easier comedy, Rob Corddry reported on voting-booth handles covered in poop bacteria. The show was such a phenomenon at that point that Comedy Central actually sold DVDs of their 2004 election coverage.

2005–2007

Midway through July, the Month of Zen stream had reached December 2005, and another Daily Show trademark made its first appearance in my monthlong endeavor: the secular War on Christmas. For a decade, Bill O’Reilly bloviated about the show’s supposed mission to stamp out religion, and for a decade, Stewart respond with, basically, this:

The next day, another staple in the Daily Show bag of tricks made an appearance. Earlier that month, an air marshal shot a passenger in a plane parked at a Miami airport. “The silver lining, at least,” Stewart argued, “is that the 24-hour networks were up and running, to bring us information and context.” Cue the montage of rampant, unconfirmed speculation from CNN, Fox News, and MSNBC.

It’s nearly a minute long, and you can practically hear the audience realize what it is they’re watching midway through. Remember, this was a period before supercuts, and YouTube was only one year old at the time. Nobody had seen a format quite like this before, laying out the media tricks and vamps so plainly and succinctly. The Daily Show made media critics out of every single one of its viewers.

It would be unfair to say that The Daily Show in this mid-00s period was on autopilot, but the Iraq War and the Bush administration supplied them with so many moments and quotes to ridicule, it allowed Stewart to keep the four-year-old war at the forefront of public consciousness. In early 2007, as the Bush administration tested the waters of a confrontation with Iran by claiming they were supplying Iraqi fighters with weapons, Stewart let Bush dig his own grave in a mid-February installment of the long running MessO’Potamia. “Here’s my point: Either they knew or didn’t know,” Bush said. “What matters is, is that they’re there.” Later in the segment, Stewart informs John Oliver that the U.S. has a long history of supplying fighters, like the Taliban, with weapons. “We son of a bitch!” Oliver exclaims in a realization at once funny, sad, and, in a way, vital in its distillation of American foreign policy.

2008

The Month of Zen gets a bit of rejuvenation when I tuned in on July 20 for a batch of episodes from July 2008. The run included one covering then-candidate Obama’s trip to Iraq — the trip where he nailed a three-pointer in front of a crowd of troops and media cameras. In a part-parody of the media’s hagiographic coverage, part-genuine celebration of Obama’s perceived “coolness,” the show pretends to send four overeager correspondents who talk about Obama like overexcited teenagers to Iraq.

Later in the episode, Wyatt Cenac heads down to Florida to get old Jews to bicker about the election. If that sounds familiar, it’s because Stephen Colbert did practically the exact same thing during the 2000 recount. The show was reusing old premises, and though I can’t really fault a four-times-a-week news show that produced thousands of episodes for recycling a premise eight years later, its redundancy was tough to ignore during a monthlong marathon-watch. The show was a well-oiled machine at this point, and it knew the best ways to get people to embarrass themselves.

2009–present

The Daily Show as we’ve known it for the past half-decade or so is a much more focused endeavor than its beginning years. In its early days, the show’s gonzo cast of correspondents ping-ponged between disparate topics with Stewart as their ringleader. (Did you know The Daily Show used to regularly review movies? It’s true!) Sometimes the guest interviews happened in the middle of the show. By 2009, the show’s format had been honed to a three-part formula separated by commercial breaks: a quote-unquote big opening segment on the dominant news topic of the day; a second shorter segment, often on a topic with less immediacy; and lastly, a guest interview.

Of the episodes I watched, the most emblematic of these A-block “big” pieces was a segment from January 2013, a month after the Sandy Hook shooting that killed 26 children, in which Stewart combines archival footage and righteous outrage to trace the government’s widely dysfunctional implementation of gun control. Stewart often tends to eschew having specific political ideologies attached to him, but the segment is the show at its best on two levels: Stewart, a man clear in his political stance, backed by a research apparatus that informs about the ways in which government has failed while also satirizing it. I can’t imagine The Daily Show even touching a situation like Sandy Hook in its early years.

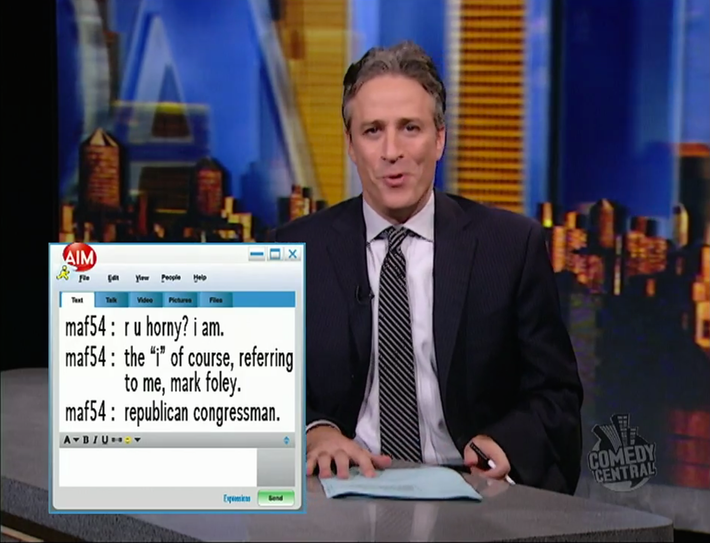

One episode during my month of viewing stuck out to me as a perfect example of The Daily Show firing on all cylinders: October 2, 2006. “Late last week, Congress approved a new detainee bill that gives the president sweeping authority. He’ll have the power to interpret the Geneva Conventions, it’ll suspend habeas corpus for non-citizens. We spent all of Friday talking about this issue, knowing that it would be our headline today. ’Cause, really, what else could happen that would be big enough to change out coverage of non-citizens losing the right of habeas corpus—”

“Oooh, right.”

The Mark Foley congressional-page scandal was a sort of perfect storm for The Daily Show. It featured a disgraced Republican congressman sending explicit sexual messages, and indicated that Republican leadership knew of it. It featured hypocrisy, as Foley had been the chairman of the House Caucus on Missing and Exploited Children. It had members of the media forced to read the sexts with gravitas. It had the setup for a great/groan-worthy pun, “Foley Erect,” and a Caligula reference.

On top of it all, the guest that day was Mississippi Republican Senator Trent Lott, whom Stewart flat-out asks, “What’s wrong with the House of Representatives? And I’m not trying to excuse the Senate, but is that the little bus that they take to the statehouse?” Later in the conversation, Stewart drops the joker façade and tells Lott, “It just keeps giving the American public the sense that no one’s in charge.” He also gently criticizes Lott for referring to Foley as having been “overly friendly.”

It’s a remarkable episode for The Daily Show and for Stewart in particular, who has his cake and eats it, too. And what’s more amazing is it’s not unique. There are countless episodes like this in Stewart’s oeuvre; an immense body of work that in many ways defined the first decade and a half of the new millennium. Jon Stewart found his groove quickly — larger events forced his hand in that regard — but that he managed to sustain that level for more than a decade is perhaps even more of a feat. Just the prospect of watching the Month of Zen was exhausting to think about. I can’t even fathom having to star in it.