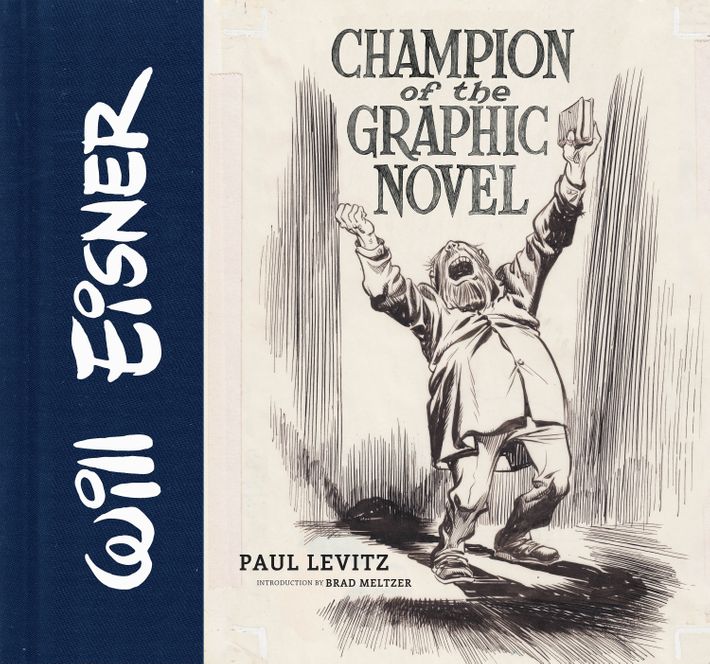

Graphic novels — that is, long-form narratives done in the style of comic books — have rocked the literary world in recent decades. Works like Maus, Persepolis, and Fun Home have garnered Pulitzers, given birth to film and theater adaptations, topped best-seller lists, and elevated comics art from a disdained medium into an acclaimed one. But who, exactly, invented the graphic novel? Debates over its origins have raged ever since the term graphic novel first came into vogue in the late 1970s. But new research is bringing us closer to an answer. The origin of the graphic novel is a bit of a detective story, and a principal suspect is the man profiled in the upcoming book Will Eisner: Champion of the Graphic Novel, written by longtime comics writer, editor, historian, and former president of DC Comics Paul Levitz.

Eisner, who died in 2005 at the age of 87, was nothing short of a titan in the world of comics. He was a writer and artist whose influence has been felt since his earliest successes in the early 1940s. Eisner’s unique career included a pioneering newspaper comic strip (“The Spirit”), helping win a few wars by showing GIs how to take care of their equipment in official military artwork, heading a company, teaching, and even doing the first comic strip to appear in New York magazine, back when it was the Sunday magazine of the New York Herald. We’re proud to present this exclusive chapter from Levitz’s book, a chapter about Eisner and the origins of the graphic novel.

***

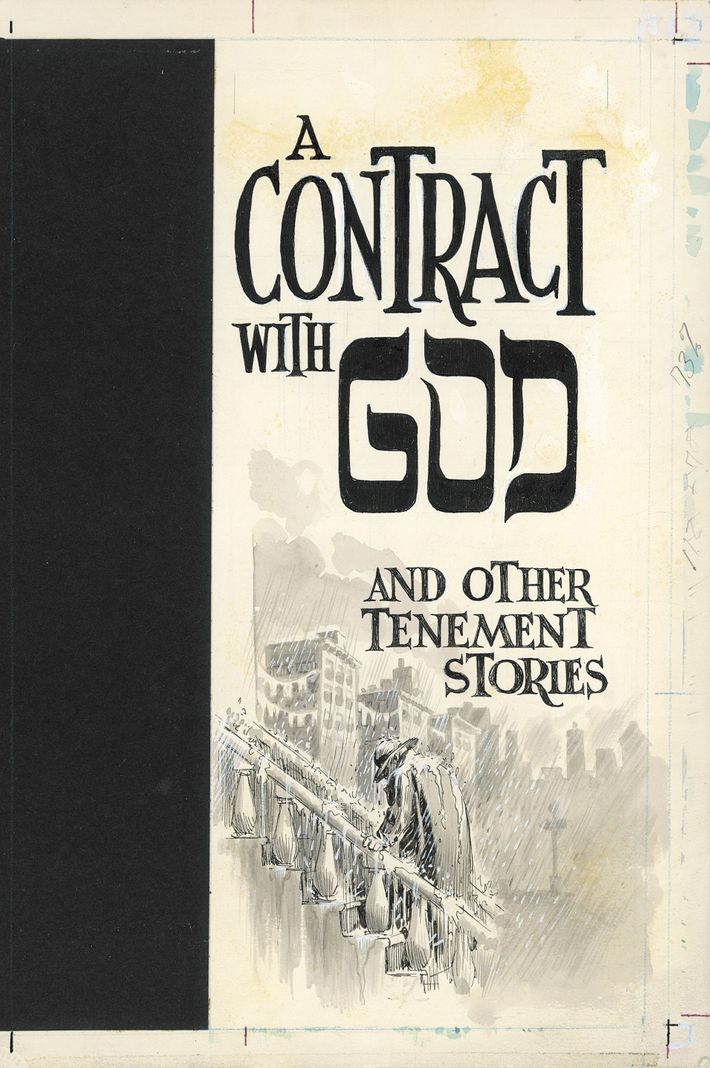

It’s common to hear Will Eisner called “the father of the graphic novel” for his near-universally acclaimed 1978 work A Contract With God and Other Tenement Stories. However, it’s a phrase that is loaded with inaccuracy, emotion, and controversy, even among those with deep respect for Eisner and his work.

Taking it step by step, first consider the term “graphic novel.” Eisner himself, in the first edition of Contract, said, “I was working around one core concept — that the medium, the arrangement of words and pictures in a sequence, was an art form in itself. Unique, with a structure and gestalt of its own, this medium could deal with meaningful themes.” But at the time there was no common meaning to the term “graphic novel,” and, indeed, almost three decades later, it remains a term replete with ambiguity and debate.

Around the time of Contract’s publication, Eisner said, “I had finally settled on the term ‘graphic novel’ as an adequate euphemism [for comic book], but the class I teach is called ‘sequential art’ — and of course that’s what it is — a sequence of pictures arranged to tell a story.” Prior to Contract, Eisner had used “sequential art” as his preferred euphemism for comics. Whether Eisner subsequently chose “graphic novel” in an act of independent discovery or subconsciously adopted it is unknowable, but the term clearly predated his usage.

Eisner had not been alone in his search for a “euphemism,” or better term, for the creative work being done in comics. Early comics fan Richard Kyle used “graphic story” and “graphic novel” in an article, “The future of ‘Comics,’” in a small-circulation fanzine published in 1964. Kyle and Bill Spicer then made Graphic Story Magazine an influential early force in comics scholarship, further promoting the terms and counting Eisner among his readers. Curiously, the words were first used to market a comic on a periodical cover: The Sinister House of Secret Love no. 2 (December 1971–January 1972). Part of a brief experiment by DC Comics to reach the then-burgeoning audience for gothic romance, it featured a thirty-nine-page story by Len Wein and Tony DeZuniga, promoted on the cover as “A Graphic Novel of Gothic Terror.” The copy was likely to have been written by assistant editor Mark Hanerfeld, a founding member of comics fandom who would certainly have been familiar with Kyle’s use of the term. Kyle, with Denis Wheary, collected underground cartoonist George Metzger’s Beyond Time and Again in hardcover book form in 1976 with the subtitle “a graphic novel” on its title page, around the same moment when Morningstar Press’s edition of Richard Corben’s Bloodstar used the term on its flap. And Byron Preiss’s Fiction Illustrated wobbled between copy describing itself as a “graphic novel revue,” “a graphic story revue,” and a “visual novel” in different editions.

Eisner had also seen the term used in 1974, in a letter from cartoonist Jack Katz describing his effort to produce The Last Kingdom, a serialized adventure comic that would take him over a decade to complete. Katz’s ambitious work bridged the final years of the underground movement into the first decade of independent or alternative comics, with elements of both building on Katz’s prior career in traditional newsstand comics. Eisner applauded the “enormity” of Katz’s project, and their correspondence appears to have continued throughout, with Katz acknowledging his debt to Eisner’s “encouragement.” Katz’s choice to describe his work as a graphic novel didn’t extend to its public positioning, as far as surviving information shows, and there’s no way to know if his use of the term stuck in Eisner’s subconscious, and no evidence yet of any resulting spread of the usage beyond their letters.

Eisner’s use of the term, however, was a turning point.

But a turning point for what? What is a graphic novel, anyway? In his original preface to A Contract with God, released by Baronet Press in 1978, Eisner went on to describe how Lynd Ward’s woodcut novels, particularly Frankenstein (which Eisner read in 1938), influenced his thinking, and how his efforts were an extension of Ward’s original premise.

Yet Frankenstein was less a graphic novel than were other works by Ward; it was really an edition of the Mary Shelley prose novel illustrated with Ward’s woodcuts. By the time Frankenstein was published in 1934, Ward had already done four woodcut novels of his own, beginning with Gods’ Man (1929), cited as the first wordless American novel. Ward’s work, in turn, was influenced by the woodcut novels of the Flemish artist Frans Masereel (author of the 1919 wordless novel Passionate Journey) and the German artist Otto Nückel (author of Destiny: A Novel in Pictures, published in 1930). Both works are considered by scholars to be the direct antecedents of the modern graphic novel. Two decades after Contract, Eisner retroactively described these as graphic novels, along with comic strip creator Milt Gross’s 1930 volume, He Done Her Wrong: The Great American Novel and Not a Word in It — No Music, Too, whose contents lived up to its title. In fact, Eisner described Ward, in the years before he began Contract, as “the father of pure ultimate visual … I’ve tried to reach that same mountaintop and have never been able to do it.”

Digging deeper, Swiss cartoonist Rodolphe Töpffer’s Histoire de M. Vieux Bois, later and better known to Americans asThe Adventures of Mr. Obadiah Oldbuck, was published as a picture novel in Europe in 1837 and came to America in 1842 as a supplement to Brother Jonathan, the first illustrated weekly in the country. Other publications that combined pictures with words followed, and almost as soon as the newspaper comic strip evolved into recognizable form, it began to be repackaged in books and magazines, including as the content for the earliest American periodical comic books.

In turn, when comic books started publishing original material, it was only a matter of time before the stories would be collected into volumes, first in mass-market paperback size, then more commonly in trade paperback or even hardcover. These collections of reprints were united by their title character or series but only accidentally had any commonality of story or theme, and their existence as books was clearly an afterthought. While the source of the contents is a meaningful fact, it’s not enough to help us define the graphic novel or Eisner’s role in its emergence as a cultural form.

As it is most frequently used today, “graphic novel” refers both to original comics work created in book form and to collections of previously serialized work. The distinction between the two is a challenge to parse and, perhaps, ultimately irrelevant. If prior serial publication were a disqualifier, then the most acclaimed graphic novel in America, Art Spiegelman’s Maus, wouldn’t fit (having originally appeared in parts in Raw, a magazine published by Spiegelman and his wife, Françoise Mouly), nor would the bestselling graphic novel Watchmen by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons (first a twelve-issue “maxi-series” from DC). Both titles helped define the form, however. The earliest compilation that seems to fit this category of graphic novel is a collected edition of The First Kingdom’s initial issues, published in trade paperback by Wallaby (a Simon & Schuster imprint) in 1978.

So if the shelves of a bookstore now include a section labeled Graphic Novels, which is likely to rack together a sequential reprint of Charles M. Schulz’s Peanuts with Chris Ware’s unique Building Stories or even Scott McCloud’s brilliant nonfiction analysis of the form, Understanding Comics … what, exactly, did Eisner supposedly father?

One argument is for looking at the evolution of comics in America as a progression of ambition in storytelling. The early panel cartoons moved to the strip format, particularly the more ornate Sunday strips, and then to the longer stories permitted in the early comic books, which very quickly moved from single-page adventures to short stories, and by the early 1940s even to the occasional “book-length adventure” of as much as sixty-four pages. But while the comic books began to tell more complex stories, their intended audience was quickly defined as children, and even enduring classics such as Carl Barks’s Uncle Scrooge (which became America’s most successfully exported comic) dealt with relatively simple subject matter and rigorously avoided any controversial or adult themes. The only relatively adult work done in comics pandered to a lowest common denominator with crime stories or outright pornography, such as the notorious Tijuana Bibles, which parodied cultural figures and comic strips in sexual escapades.

The 1950s brought some steps forward. St. John Publications launched their version of a picture novel in 1950, producing basically long comics (more than 100 pages) with adult (or at least lurid) themes. Arnold Drake and Leslie Waller did It Rhymes with Lust, and Manning Lee Stokes and Charles Raab produced The Case of the Winking Buddha, but then the line died. Whether they’re considered early graphic novels is partially a question of the legitimacy of genre fiction in the ancestral family tree: Drake would argue in his later years that Lust was the first graphic novel, only to have many scholars overlook it as a conventional genre comic simply produced at greater length in book format.

If the definition of “graphic novel” is to include ambition in storytelling and, indeed, the complexity and originality of plot that is an ideal for the prose novel, then publications such as It Rhymes with Lust should ultimately be classified with the longer super-hero stories of the 1940s comic books. Genre, in extended form, can be rewarding for the reader, but the difference is more quantitative than qualitative.

More significant movement toward challenging creative content happened at E.C. Comics, as publisher Bill Gaines aimed for a more sophisticated audience. Like Eisner, Gaines had great appreciation for short stories with twist endings, and he brought those sensibilities to the comic book line he inherited from his father, Max (pioneer of the modern comic book in the late 1930s). In their horror and science fiction comics, Gaines and editor Al Feldstein included morality plays with dimensions an older reader could appreciate; and in the war comics, and especially in MAD, Harvey Kurtzman broke all the rules. Kurtzman was a brilliant cartoonist and a total perfectionist, layering the MAD parodies with humor that would deeply influence American popular culture for decades to come. MAD hit that ideal of dual-layered storytelling: entertaining for children and adults alike, with different messages for each. The phenomenon ended too soon: Gaines and Kurtzman split over economic differences just as MAD was changing format from a comic book to a magazine in order to survive the late 1950s downturn in the comics field.

Before MAD changed, though, it fueled an important step in the evolution of the graphic novel: the first mass-market paperback reprints of American comic book material (albeit black-and-white), beginning with The MAD Reader, published by Ballantine Books in 1954 and edited by E. L. Doctorow.

The MAD paperbacks were successful, and when Gaines shifted the series to another publisher, Ian Ballantine first tried to replace them with reprints from Kurtzman’s next magazine, Humbug. Ballantine also commissioned Kurtzman to create a new book. The result was Harvey Kurtzman’s Jungle Book (1959), the first all-original comics in book format and a recognizable prototype of the current graphic novel.

The volume had terrible production values, reflecting the fact that it was so experimental, and it failed commercially, so Kurtzman never produced a second.

The continued success of the MAD paperback reprints also led to a companion series of original paperbacks by MAD cartoonists carrying the MAD brand. Beginning in 1962 with Don Martin Steps Out, and continuing for three decades, few of them were more than collections of original gags, if in somewhat longer lengths than the magazine format usually permitted. But a few, beginning with Don Martin’s The MAD Adventures of Captain Klutz, began to build a true story spine through their length.

The books were ubiquitously distributed in the early years, and it’s likely Eisner was aware of them; not least because former Eisner and Iger studio artist Dave Berg published a shelf’s worth of MAD originals beginning in 1964.

The 1960s and early 1970s were heady times for comics in America: for the periodical publishers, sales continued at a healthy pace, and the pop art and camp phenomena allowed the form to connect with the broader culture, thanks to the massive sales of Peanuts and the various mass-market paperbacks filled with super heroes. Social issues and a less sanitized view of society began to appear in the periodical comics, but they were still fundamentally children’s publications, if now for brighter, more socially aware young people.

Simultaneously, the underground comix exploded in the counterculture, with Kurtzman as the godfather of their movement. Kurtzman’s questioning of establishment thinking had permeated MAD and its successors, and their biting humor had inspired young cartoonists to go around the conventional publishing system in search of free expression. Some of the creators were cartoonists Kurtzman had personally encouraged, such as R. Crumb, whom Kurtzman almost hired as art director for one of his short-lived magazines; others he had inspired by the courage of his storytelling. The stories were mostly short, outrageous, unsettling, and uncensored by publishers, distributors, or any other intermediaries, unlike every other form of popular culture. The talent that percolated here would be vital to the emergence of graphic novels but had no real opportunity to produce works in a form that could be seriously considered novels, because of the anthology format and irregular publication frequencies that characterized the undergrounds.

In many ways, in the 1970s American comics had probably hit their lowest creative point since their inception. Their first great delivery mechanism, the comic strip, was being challenged by a steep decline in the number of newspapers in major cities, and the last truly successful adventure strip, Spider-Man, was launched in 1977. Mainstream comic books were facing a diminishing number of newsstands connecting them to their audience and had largely alienated their creative contributors. (The growth of the comic book shops and improved creator contracts that would lead to Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns were still in their infancy.) Television channels were increasing, and in particular the amount of children’s programming had expanded, which many publishers blamed for a generation’s growing disinterest in mainstream comic books. And the fire that was the underground seemed to be burning itself out. If there was to be a next flowering of the medium, it would have to be in a new format, and adventurous creative people were looking for it: a true case of necessity being the mother of invention.

Exploration was in the air, and it was infectious — a “meme,” to use another term coined at about the same time as “graphic novel.” Creative talent from the comic strips and periodicals and the undergrounds were connecting, experimenting, and searching for new forms. Longer works launched, such as Katz’s The First Kingdom in 1974, with its ultimate over-700-page length when collected, or Dave Sim’s monumental Cerebus in 1977, which would run 300 issues and some 6,000 pages over twenty-seven years.

Gil Kane, long a star of the DC and Marvel art staffs, created a swords-and-sorcery tale entitled Blackmark (with writer Archie Goodwin), and convinced Bantam to publish it as a mass-market paperback in 1971, the first original comic in book form since Harvey Kurtzman’s Jungle Book. Like Kurtzman’s project, Kane’s failed to convince the publisher to follow with a planned sequel.

Burne Hogarth produced two Tarzan hardcovers for Watson-Guptill in 1972 and 1976, taking the Edgar Rice Burroughs hero from his classic newspaper strips to a new, more direct adaptation of the original novels.

Publishing entrepreneur Byron Preiss began a short-lived line entitled Fiction Illustrated, notable for books such as Steranko’s Chandler: Red Tide (1976), produced in an inexpensive digest format that mixed type and comics art.

Projects across the medium grew larger and more ambitious: Even traditional publishers Marvel and DC united in 1976 to produce a ninety-six-page, tabloid-size Superman Vs. the Amazing Spider-Man comic book story by Gerry Conway, Ross Andru, and Dick Giordano, arguably the most “booklike” project from either publisher and more commercially successful than any previous original graphic novel, if it is to be counted as one.

Each of these projects attempted to stretch the boundaries of comics in ways that were visible to the reader, and less visibly in the ways their business structures were published. There were shifts in pricing and distribution methods, notably on Superman Vs. the Amazing Spider-Man, which expanded on a several-year effort by the mainstream comic book companies to find new outlets with their tabloids that offered retailers a more competitive price per copy than the historically cheap comics (a cover price of two dollars as opposed to twenty-five cents). Richer color and better printing on Hogarth’s Tarzan demonstrated that the higher production standards of Europe could be addressed in America, if not yet equaled.

One of the influences raising this temperature was an increasing awareness of the diverse creativity of comics across the world. In 1977, the publishers of National Lampoon began publishing an American edition of the French bande dessinée magazine Métal Hurlant, showing off the lush artwork and color typical of the albums and magazines produced in much of Europe, but which had virtually never been brought across the Atlantic. A few years later, Heavy Metal would also be the first place to publish a Japanese manga story in direct translation, and its launch helped American comics creators become conscious of the greater respect comics were given in other countries, and of the far greater opportunities for using comics to address different subject matter — even if they often couldn’t read the material.

By 1978, an explosion was about to happen. The only question was, what would be the spark. Ambitious projects were coming to the market that had been developed over the previous few years: Jules Feiffer was doing his “novel in cartoons” Tantrum for Random House; Preiss was readying comic-style adaptations by Howard Chaykin of edgy science fiction novels by Alfred Bester (The Stars My Destination) and Samuel R. Delany ( Empire) for Putnam Berkley as hardcovers; Simon & Schuster’s fireside imprint was preparing to follow its successful Marvel trade paperback reprints with an original story, The Silver Surfer: The Ultimate Cosmic Experience, reuniting two of the men who had made Marvel a phenomenon, Stan Lee and Jack Kirby. And with their focus on the infant market of comic book shops that was springing up all over the country, Dean and Jan Mullaney’s Eclipse Comics commissioned an original from Don McGregor and Paul Gulacy entitled Sabre in the European “album” format. Each of these would be produced with production values beyond anything used either in American comics or in the earlier original experiments.

But somehow, it was Eisner’s A Contract with God that would matter most to the generation of creators who would follow.

***

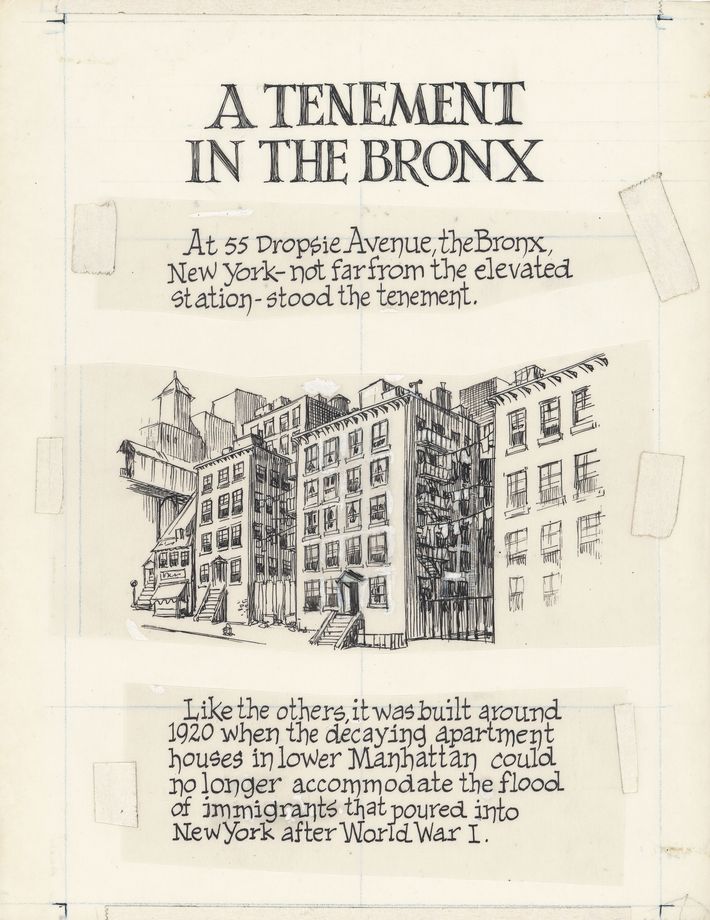

If you picked up one of the 1,500 copies of the first edition of A Contract with God offered through comic book shops, you would be holding a volume that outwardly appeared to be much like every traditional hardcover on your shelf: No illustration marred the type on its cover; there was no dust jacket; and no copy indicated that it was a graphic novel, comic, cartoon, or anything other than the serious literature that Eisner dreamed it could be treated as. But inside you were immediately pulled into Eisner’s world, with endpapers of the dingy alleys of the Bronx, the skyscrapers of Manhattan faintly looming in the distance, and a defeated man making his way up a staircase.

Inside, a heavy cream stock with sepia ink seemed to age the drawn images and helped transport the reader back to early-twentieth-century New York, while adding gravity to the project both symbolically and physically, giving the book a weight beyond that of a prose novel of similar page count. After a brief statement of his history with The Spirit and his intent “to tell how it was in a corner of America yet to be revisited,” Eisner abandoned type and went into the medium he had spent a lifetime mastering, using sequential images and hand lettering to tell his story.

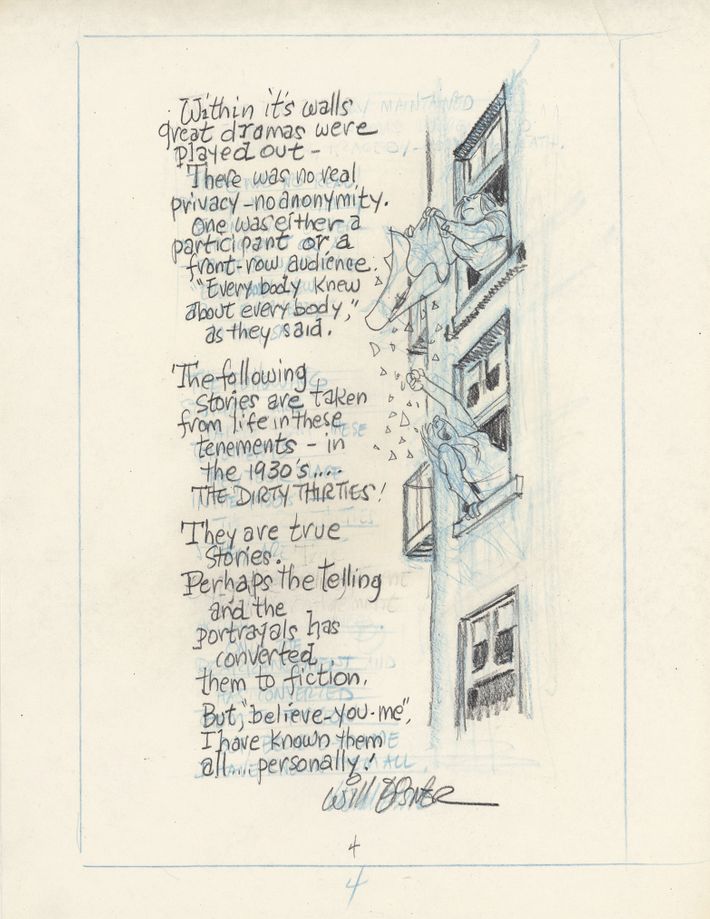

Contract included four stories, one of the arguments occasionally raised against it being a true novel. Yet although the characters never meet, they are firmly linked in place and time, as Eisner’s opening pages about “a tenement in the Bronx” clearly declares his intentions for 55 Dropsie Avenue. From there, he moves to deeply human stories — what Eisner describes as “a narrative with intimate themes.” Part of its impact would surely come from the fact that the subject matter of each story touched upon aspects of the human condition previously reserved for prose or film and rarely glimpsed in cartooning.

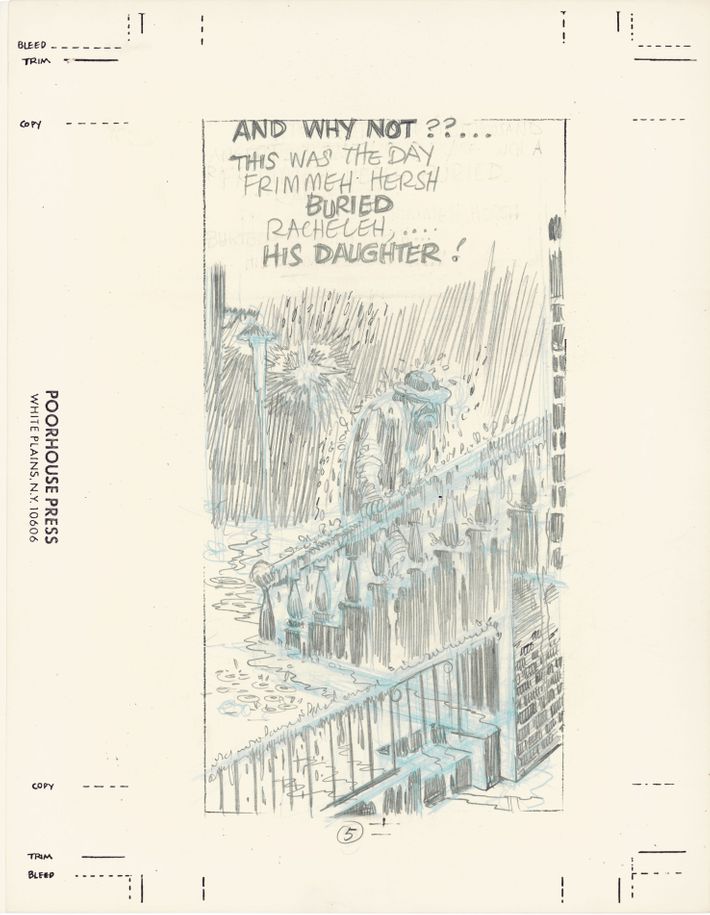

The title story tells of Frimme Hersh, an observant Jew raging that God had broken their contract when his beloved adopted daughter Rachele died at age sixteen. The emotional fury that Eisner was cathartically exorcising here went beyond any captured in his other work. Hersh abandoned his religious practice and moral principles and grew rich. But ultimately he returned to his roots, asking the elders of his tribe to draw up a new contract for him with God, only to have his life end in a sudden heart attack in the midst of his hubris celebrating the agreement. A brief epilogue shows a young man named Shloime Khreks picking up the fallen contract, and the cycle of life begins again.

If the emotional power of the story came from Alice’s death and Eisner’s search for meaning from the tragedy, it’s possible the title was from a different connection to his past. In the years of Eisner’s youth, many popular cantors had recorded a folk song entitled “A din toyre mit Got,” which can be translated from the Yiddish as “A plea to God,” or a lawsuit or judgment against Him. Its origin was a prayer by Rabbi Levi Yitzhak (1740–1809), and it has been repeatedly translated into song.

Having addressed the “intimate themes” of death and man’s relationship with God, Eisner moved on in the three shorter stories that round out the volume to deal with sexuality and ambition and the complex motivations that can tie the two together. “The Street Singer” tells of a young man seduced, given hope of apparent opportunity to change his life by a fallen diva, only to lose it in his alcoholic haze. “The Super” of the tenement is the utterly unpleasant Mr. Scuggs, driven to suicide by the innocent-appearing but manipulatively evil ten-year-old Rosie. And the book ends with “Cookalein,” taking some of 55 Dropsie’s inhabitants up to the Catskills for a story of romance and rape, a decade before Dirty Dancing made the setting familiar to people far from New York City.

***

Despite the taboos it had broken and Eisner’s efforts to have it published in dignified form, like each of the other prototype graphic novels of its time Contract had very limited impact in the commercial world. It was neither a bestseller (by any definition of the term) nor something a publisher could look on as a surprise success. Instead, it had its greatest impact on the creative community, serving as a role model, as Eisner himself so often did in his life.

First of all, Contract was ambitious both creatively and in its commercial form. Eisner had talked about comics as an art form for decades, with Feiffer, as his pencil swept across Spirit pages, or to any interviewer who would listen. By the time Eisner was starting up Poorhouse Press, he was determined “to spend the rest of [his] life producing ‘comic literature.’” Initially the Poorhouse projects were either educational or pure fun, but they hardly rose to the test of being considered literature. It wasn’t until the summer of 1976 that Eisner commenced work on something he initially described as “a comic novel.” It was a level of risk that Eisner was unused to taking. “For the first time in my career I had no publisher,” he recalled. “I had nothing presold.”

Contract was not an extended version of something a traditional comic book publisher might have produced, and it didn’t draw on genre conventions, such as the reluctantly adopted mask for The Spirit, or other creative crutches. Consistent with his pattern of later years, Eisner didn’t share his work-in-progress easily; lacking a specific model for his project meant he could explore in many directions. In early correspondence he referred to his project as A Tenement in the Bronx, and it wasn’t until many years later that any but those closest to Eisner knew that he was drawing on the well of the deepest tragedy of his life to shape his story. True art is often personal and forged from pain. For many decades Eisner would not talk of his daughter, Alice’s, death from leukemia at sixteen in 1970, or of the echoing tragedy of their son, John, whose life would be permanently derailed by his sister’s death. But whether his readers knew it or not, the honesty of Eisner’s portrayal of a man torn from God by the death of his daughter shone through every page of the work.

This was adult literature in the best sense: looking at life, death, and the choices human beings make in their journeys. Whether Eisner was successful or not, readers will have to judge, but he would not toss off the stories of his tenement dwellers to get a simple laugh — not without adding the grace notes of tragedy as well.

Eisner’s quest for respect came through in the package, the publisher, and the lengths he went to accomplish both. Each of the other 1978 “experiments” took their physical format cues from a comics presentation: European albums, where comics were produced more lavishly; American comic book proportions, merely printed on better paper and more securely bound; or the horizontal orientation of the comic strip. Eisner wanted a book that could sit comfortably on a bookstore’s shelves next to prose novels as their equal. He was determined to have a “New York publisher” behind the book, counting on that to ensure solid distribution and marketing. He was turned down by publishing’s wise men and went with a smaller but still mainstream company, Baronet Press, for whom he had done sports-themed calendars through Poorhouse Press. If necessary — and ultimately it was — he was even prepared to quietly invest in the project himself to achieve his aims. He overcame the production limitations that had defeated Kurtzman two decades before, with his story, now called A Contract with God, full of perfectly reproduced artwork, even rendered in sepia ink to evoke the times past he was depicting.

Second, Contract was centered in a form that evolved from comic books. Eisner had spent a lifetime learning the tools a cartoonist could use to communicate with different people in many different ways, and he brought them all to A Contract with God to make it something new without moving it too far from its roots in comics. He wanted a new audience, but there was a recognizable continuity with what came before, too. As Neil Gaiman commented about Contract, “It used panels.” Feiffer would keep Tantrum recognizable to readers of his strips; Preiss’s projects fought against their predecessors with cold type, static layouts he forced on his artists, and a dependence on writers from science fiction either for adaptation or as originals that remained squarely within genre; and McGregor said he “wanted to give [comic book readers] a choice” with Sabre, making it a more mature take on genre tropes.

Third, Contract was unexpected. While Eisner was highly regarded as a founding father of the comic book world, and a brilliant cartoonist, his reputation was based on The Spirit and, to a lesser extent, on his work from Poorhouse Press, which was educational or harmlessly amusing and certainly niche. Suddenly, Eisner was taking on very serious subject matter, not merely doing a longer or better produced story in the genre or style he’d previously used, which would be the perception of the other experiments of 1978: a step forward, where Contract was a leap.

Fourth, Eisner was unashamed. After toying with using the subtitle “An Experiment in Storytelling,” the trade edition of Contract bore the words “A Graphic Novel” in big, bold type, inviting readers to a new experience as no publication had before. (The limited-edition hardcover, intended for Eisner’s existing fan base, had only a sedate title treatment and Eisner’s stylish signature on its case.)

And perhaps ultimately most important, Eisner was persistent in realizing that the theoretical goal he’d espoused decades before was becoming attainable, and that his work on A Contract with God and the graphic novel format could be his legacy. By comparison, Feiffer initially produced Tantrum to fulfill a long-time ambition: “I wanted to do a novel in cartoons by the time I was fifty, and I just made it. Once I did it, I loved doing it, and I swore I’d do more. Then I lost all desire, and having done it once never wanted to do it again.” With neither Knopf nor the public clearly clamoring for more, Feiffer went on to other forms, not returning to the graphic novel for over three decades. Preiss’s books left his collaborators worn out financially and emotionally. Of the 1978 alumni, only McGregor would jump back quickly.

If Eisner felt that God had broken their contract when He took Alice, Eisner had entered into a new contract, as evangelist for a new form, and finally earned the respect he and his fellow cartoonists deserved.

Excerpt from Will Eisner: Champion of the Graphic Novel by Paul Levitz

Published by Abrams ComicArt

© 2015 Paul Levitz