Over the past decade, Alexandre Desplat has quickly made a name for himself as one of the best and biggest film composers currently working in Hollywood. A quick look at his curriculum vitae will prove just how versatile he is, having been at the musical helm of numerous franchise movies and Oscar bait alike, from political thrillers (Syriana and Argo) to subdued dramas (The Imitation Game and The Curious Case of Benjamin Button) to blockbuster fantasy adaptations of Harry Potter and Twilight to, most notably, the idiosyncratic Wes Anderson universe. “I enjoy going from genre to genre, just as I like watching different genres of movies,” he tells Vulture over the phone from Paris. “I try to jump from a drama to a thriller to a biopic or a love story; it allows me to take chances in different territories.” With two new films that he composed the music for out in recent weeks (Suffragette and The Danish Girl), as well as Lucasfilm’s highly anticipated Rogue One: A Star Wars Story space opera coming out next year, we asked Desplat to share the stories and inspirations behind five of his most well-known scores.

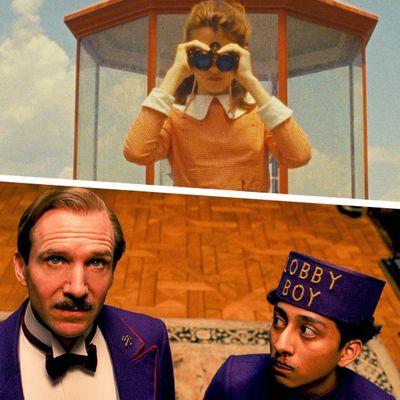

The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014)

Desplat received his first Oscar win for The Grand Budapest Hotel, which was his third collaboration with Wes Anderson. “It might have been closer to Fantastic Mr. Fox because of the unique material. The melodies are definitely catchier in Budapest than Moonrise Kingdom,” he says, noting that it’s much more of a “moving” score in the sense of memorability. “I knew how to appropriately combine and play with the sounds. The great idea that Wes had was to get rid of any string instruments, and that created another dimension of sounds. It created another mood and atmosphere that was very airy, joyful, and light at the same time.”

Desplat also notes that Budapest was the first film that he and Anderson collaborated on that was almost entirely composed of original score — all but four songs. “It was very different to write for all of the action,” he continues. “I must say, music in Wes’s films is crucial. It’s really part of the DNA of the film. What melodies belong to what characters is also an aspect of his music, and captures the aspect of his films so beautifully.” When we ask if there was a scene that was particularly enjoyable for him to compose for, he takes a moment to contemplate. “When we first go into the hotel, there are such rich and stunning images, you can’t help but think about what music should accompany them,” he says. “When Jopling goes to the museum and kills Kovacs, there’s the long chase scene, which was a lot of fun to write. It’s a very sonically intense frame, and Wes gives me a lot of liberty for me to be experimental. He lets me explore and I try to surprise him with ideas. We send ideas back and forth and we’re really excited about what we’re doing. It’s very quick and very enjoyable exchange that we have when we work together.”

Moonrise Kingdom (2012)

Despite Desplat not receiving an Oscar nomination for his work on Moonrise Kingdom, the film (which was his second collaboration with Anderson) propelled him to immense recognition with the score’s playfully quaint aesthetic. “Having already worked with Wes on Fantastic Mr. Fox, I was already exposed to his world of whimsy and irony. So when I did Moonrise, I remember the reference was that it should be peaceful for children. By putting together the strange instrumentation, with the seven parts and the orchestra slowly but surely moving, and the choir building on top of that, it gave the sensation where we were following the path of the two children. We follow them, but they have their own space,” he says, specifically mentioning the epic seven-part suite “The Heroic Weather Conditions of the Universe” that unfolds throughout the film’s narrative.

“They connect with their childhood to the music, but they’re now heading towards their freedom. There was this sensation of freedom that was the goal, giving an excitation,” he continues. “Like when you’re 11 or 12 and you go to camp with friends in the summer, there’s the expectation that there will be adventure and fun and that you’ll meet new friends and maybe make a new love. That was exactly what we were trying to achieve with the music, and I think we achieved it quite well.”

The King’s Speech (2011)

“There were two main elements,” Desplat says of The King’s Speech score, which earned him his fourth Oscar nomination. “There’s the friendship between George and Lionel that will come from their therapy, the friendship between them as two partners, and the possibility of the king finally expressing himself. Very early on in the film I wanted to have the audience feel that. I love when I write a score to be able to present who the character was before the film, or who the character will be after the film – the past and future of a character.” Desplat worked closely with Tom Hooper, the film’s director (who he would later collaborate with again for The Danish Girl), to flesh out the film’s signature sound, which at first proved challenging. “When he’s giving his speech at the very beginning, you immediately think, He can’t talk. But why? There’s more at play there. You look at his past childhood trauma, and it comes through when he’s talking about his childhood. The fact that he can’t speak or express himself is connected, and it led me to write a piece of music that didn’t unfold; it couldn’t be a melody. It took me awhile to understand that it couldn’t be a melody. Because how could it be a melody, or a structure, if he can’t even say three words in a row?”

How was he able to work past this initial sonic conundrum, then? “I remember Tom Hooper saying that [George] was stuck. So the music should fit that, and that’s why I suggested to Tom to just have one note repeating itself,” he says, proceeding to break out into an impromptu singsong of da da da da da da. “The first time you hear these notes getting somewhere is the speech at the rehearsal near the end of the film. George has no actual melody; the only melody is of the friends and the friendship itself.”

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Parts 1 and 2 (2010, 2011)

The final two films in the Potter universe proved to be a new and exciting, albeit nerve-inducing, project for Desplat. “It was my first really huge project of that kind. There were two episodes. It was the end of the franchise, and I was coming after the years where John Williams had been at the helm,” he says. “It was a big challenge for me, and I knew it would be listened to, heard, and criticized. And I knew I had to write for each episode over two hours of music. It was my biggest challenge at the time in the studio, creating that magical, otherworldly sound.”

He notes, though, that composing the music to accompany well-known literary scenes was “very fulfilling” to him as a composer. “I think the challenge I’m currently facing with Star Wars [Rogue One: A Star Wars Story] would be a challenge of the same type, and with the ghost of John Williams’s music in the back of my head again. There’s so much to write and be proud of, and I’m proud of how I did Potter.”

The Queen (2006)

Desplat received his first Oscar nomination for the critically acclaimed drama chronicling the Royal Family’s treatment of Princess Diana’s death. “When I first saw it, it was so good. I remember saying to [director] Stephen Frears that it would work as well without music. But he told me, ‘No, you have to write the music,’” he says with a hearty laugh. “There’s a certain whimsical wit in Stephen’s films, and I felt I should capture that, and that’s what I did by using instruments that would remind us of the 18th century, which is a great time for the monarchy.”

With the film set in the late ‘90s, though, he had to strike a harmonious balance between the ornate and the modern. “I took this angle of the 18th-century palaces and castles and used this sliver of time, but not using it in a Baroque way, but instead using the same instruments that inevitably would remind you of that time,” he says. “I thought it was fun to do that. But at the same time, it’s a tragedy, because the death of Diana is tragic, and the way she was treated was rather ugly. So there’s also watching how people around her despised her and how her death was not really well-handled. That was all of the political subplots, with Tony Blair and such. I looked at the Queen herself with a bit of irony, but also with respect. It’s hard not to be moved by her. These kinds of movies are very tricky to find the tone of.”