“There was no way I was going to just do the voice. C-3PO is an integration — look at the light on that tree!” Anthony Daniels, the only actor who’s appeared in every Star Wars movie, tromps briskly through London’s Regent’s Park on an unseasonably balmy Halloween afternoon. We’re due shortly at his home to catch the Rugby World Cup final. Speaking into the digital recorder he swiped from me at the start of our walk, he recounts his first chat with J.J. Abrams, the director of Episode VII: The Force Awakens.

Abrams offered to put another actor inside the stiff and fussy protocol droid known as C-3PO, thus sparing Daniels a few months in form-fitting plastic. Daniels flatly declined. On our walk, he’s suited more comfortably: chambray shirt, jeans, and a peacoat that hangs loosely on his frame, still slight and sleek at 69. “Now,” Daniels says, as crisply as 3PO, “I’m part of the — what is the word?”

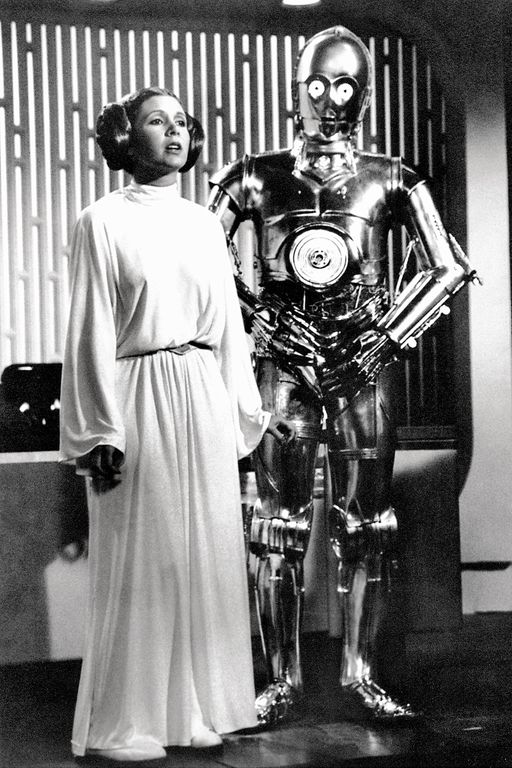

Carrie Fisher recently called them “legacy players.” Mark Hamill, Harrison Ford, and Peter “Chewbacca” Mayhew have all returned for the first proper sequel to 1983’s Return of the Jedi. (Forget George Lucas’s prequels; many would prefer to.) “I keep calling us heritage players,” says Daniels. “I feel more like an heirloom on the mantelpiece than anything.”

Daniels stops short and points beyond the trees, toward another iconic relic, the retro-futuristic cylinder of the BT Tower. “They turned that into the biggest lightsaber in the galaxy,” he says — in celebration of the 2011 Blu-ray edition. “Imagine a huge shaft of light, a bit like the 9/11 memorial, out of the top.” Daniels had the honor of pressing the button that shot the blue beam spaceward. “They said, ‘We never let anybody up here, but you’re special, come inside’ … that was a treat. I get to do treats sometimes.” He pivots back to Force Awakens. “No, the new cast, they have lived the experience of being an audience member. Pretty amazing.”

J.J. Abrams first saw Star Wars when he was 11, and grew up in an age when fandom went from lonely obsession to superhero multiverse. Now he’s gotten to direct its aging stars — action figures come to life. The most loyal among them is a former stage actor who auditioned reluctantly for “some low-budget sci-fi movie” and wound up a golden robot for the rest of his life. Daniels can be a prickly ambassador, publicly tweaking the Ewoks, the suit, the actors, and Lucas himself. But what true fan, Abrams included, hasn’t had a beef with the franchise? Like 3PO and R2-D2, Star Wars and Daniels have something deeper than love: commitment. “People say, ‘What’s it like to go back to C-3PO?’” Daniels says. “Well, I never left him.”

Photographs: David James/Courtesy of Lucasfilm; CBS/Photofest

When Disney paid $4 billion for Lucasfilm in 2012, it acquired a franchise accused of abandoning its biggest fans in favor of flashy CGI effects. Abrams has been vocal about wanting to recapture the corporeality of the early movies. Technology may have evolved since George Lucas’s multi-billion-dollar franchise premiered in 1977, and C-3PO and the Millennium Falcon could easily be digitized, but Abrams wouldn’t hear of it. Behold, they’re both back, and so is Harrison Ford! Ford knows just how real the Falcon is; its door broke his leg on the set of The Force Awakens. (“Accidents happen,” Ford told me.)

Daniels was a witness to the original ship’s destruction. “Do you know I own six pieces of the Millennium Falcon?” he says shortly after we meet at a bookstore near his home. He’s just bumped into a Lucasfilm employee who is in town to work on Rogue One, one of three spinoffs Disney will release during the core trilogy’s off years. “I found them burning it on the back lot one day,” Daniels says of the Falcon. The staffer shakes his head: “The industry was very willing to destroy its own history for many years. Now there’s the realization that —”

“It can make you money,” Daniels interjects.

“There’s a lot of value,” says the employee.

Daniels wasn’t always so fond of sci-fi — he walked out of a screening of 2001: A Space Odyssey — but he built miniature theater sets as a child, and had an early passion for acting. Growing up in Herefordshire (“You could call it ‘Poshville’”), he picked up “received pronunciation” — the Queen’s English so appropriate to a protocol droid. His father, a chemical engineer working in plastics, persuaded Daniels to study law. But he dropped out to pursue hospitality management. He hated that, too, but stuck it out, thinking, “I cannot be seen to be a failure at everything.”

Two years later he went to drama school, and finally thrived. An acting award led to a radio internship with the BBC. Walking to its Marylebone headquarters, he would pass “a magnificent Georgian house,” which he promised himself he would buy one day. “That house is probably 10 million pounds now, but I live next door to it, so that’s as good as it gets.” He also owns a home in the South of France.

In acting, too, Daniels achieved something next door to his ambitions, but those were hazy to begin with. “I never worked out what I wanted to act in,” he says. Recruited by the Young Vic, he arrived at the West End in 1975, in Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead. “He was very dedicated, very serious about acting,” says Christopher Timothy, who played Rosencrantz (and went on to star in All Creatures Great and Small). “We were actors struggling for work.”

George Lucas was holding Star Wars auditions a few blocks away, and the next thing Timothy knew, his friend was playing a robot (he also persuaded Timothy to try out for Han Solo). Daniels hadn’t wanted to audition, but his agent had said, “Don’t be stupid.” During a five-minute tryout that turned into an hour-long conversation, Daniels found himself sucked in by a painting from conceptual illustrator Ralph McQuarrie: An Art Nouveau rendering of C-3PO stares out from a desolate world. “He seemed a bit lost,” says Daniels. “He had a vulnerability that attracted me.”

Six months after being stripped down by “two plasterers in overalls,” he was presented with the finished suit: roughly 30 pounds of plastic and fiberglass, beauty and pain. “I think they didn’t realize our skin actually moves, articulates by itself,” says Daniels. “It was a nightmare. I was cut pretty much everywhere.” It took up to two hours to put on and take off. Sometimes cast and crew would break for lunch and leave him practically immobile in the heat. Daniels once resorted to mutilating an arm piece so they could make one that fit better.

A slightly more comfortable upgrade for Jedi reportedly cost $300,000 (or more than $700,000 in 2015 money). Almost 40 years later, Daniels asked Abrams if they might “rethink” the suit more radically for Episode VII. Now it’s 3-D-printed in-house; if a piece so much as chafes, it can be replaced almost instantly. (And no, he won’t say why 3PO’s left arm is now red.) But back in the early ’80s, he told People magazine, “I really would have liked to smash the costume up with a sledgehammer … I had an awful lot of hostility toward the costume and the character.” He was also initially barred from revealing his role. “I think George wishes that C-3PO was a machine,” he told People. “Performers are a problem for him.”

C-3PO’s lines were muffled by his elaborate headgear on set. So in 1976, Daniels traveled to the U.S. for the first time to rerecord them. “I walked into the sound producer’s stage on Highland,” he remembers, “and the engineer said, ‘Huh, interesting. We spent a couple of months trying to find a voice for your part because George really hates it.’” Lucas had imagined the droid as a used-car dealer from the Bronx. “He’d never thought of him being a British butler. But he had the generosity of spirit to change his mind. Had it not been for that, I wouldn’t have been in Episode V.”

Timothy remembers Daniels’s shock at the time: “Jesus Christ, can you imagine if they hadn’t used his voice? It wouldn’t have mattered a monkey’s fucker who was playing it, would it?” Darth Vader actor David Prowse wasn’t so lucky; he only learned in the movie theater that Lucas had used James Earl Jones’s voice. “It’s basically ruined my whole career,” Prowse once said.

Photographs: Courtesy of Lucasfilm; LucasFilm/Photofest; Courtesy of Lucasfilm; John Wilcon/Courtesy of Lucasfilm

Less than a year after dubbing C-3PO, Daniels returned to L.A. to sink his feet into the Hollywood Walk of Fame. In those first years after Star Wars, he envied the robot’s fame. On the street he was never recognized as 3PO, but in auditions he was recognized for nothing else.

“People would be very disposed to think I was only 3PO,” he says. “As the years went on, I was getting the sort of television roles that were not in any sense rewarding — the sorts where maybe there’d be an uncomfortable pause in the conversation if I weren’t there.” He played a pathologist in Prime Suspect and a priest in I Bought a Vampire Motorcycle.

That’s not to say he wasn’t in demand — as C-3PO. For all of Daniels’s gripes about Lucas (“J.J. is more collaborative,” he recently said), he still credits the producer as a marketing genius. “The clever thing that George did is what people have called ‘the sandbox,’” he says. That is, Lucas let other creators play with the narrative, unleashing an expanded universe of branded spinoff games and cartoons. Daniels has voiced many of them. He also consults on theme-park rides, writes for newsletters, and narrates a touring Star Wars concert. He learned a lot, he says, while trapped in plastic as tech repairs dragged on. In 2004, Daniels traveled to Pittsburgh for C-3PO’s induction into the Robot Hall of Fame. It serves as a showcase of Carnegie Mellon’s Entertainment Technology Center, a master’s program for future Imagineers. The faculty was so impressed with Daniels that he was hired as a “visiting scholar.” Two weeks every semester, he lectures on great moments in robot history (mostly his own) and samples games as a “naïve user.”

“He is the perfect play-tester,” says the ETC’s Shirley Saldamarco. “But his biggest draw is that he genuinely cares about the students. People come away really liking Anthony Daniels, and I think that’s because he really likes people.”

During lectures, and especially at conventions, he finally gets to play a character other than 3PO, not a fussy robot but a self-consciously vainglorious emcee. At this year’s Star Wars Celebration in Anaheim, Daniels aborted his first entrance by giving the presenter a new introduction (“Congratulations! You have proved your superior intelligence by selecting the No. 1 show to see at Celebration!”). Properly presented, he reentered through the crowd, milking applause in a glimmering gold jacket, the bastard child of Ricky Gervais and Stephen Colbert.

He’s an emcee with an edge, and so is the actor who plays him. Daniels has a history of candid gripes over cast, crew, and costume. (See the recent Metro U.K. headline “Why C-3PO Ain’t Too Popular With Fellow Star Wars Cast Members.”) R2-D2’s Kenny Baker once called him “the rudest man I ever met.” Daniels usually avoids comment on Baker (as he did with me), but he has said that R2 “might as well be a bucket,” and recently revealed that the three-foot-eight, 81-year-old Baker doesn’t appear in Episode VII at all — credited only out of respect for a “talisman.” (A Baker spokesman says that he did visit the set, but only as a “consultant.”) Yet C-3PO is a talisman, too. Every artifact of the old Star Wars, from the Millennium Falcon to John Williams’s score to Princess-now-General Leia, is a talisman of retro authenticity. Why else would you have Chewbacca played by a 71-year-old with two knee replacements?

What’s really at stake for Daniels is what kind of talisman he is. Is he man or robot, the agent of his own destiny or just an exceptionally well-articulated collector’s item? In a 2008 documentary, Baker remembered asking his taller half at a convention, “Why don’t you and I go out on more of these and we’d clean up, just the two of us?” Daniels had begged off, saying, “I don’t do many of these.” That may sound snobbish coming from someone who lives off the same brand. But maybe you could forgive an actor for distancing himself from nonspeaking players cast purely for their size.

Harrison Ford warns against the common mistake of confusing Daniels with the droid. “He’s greatly more sophisticated,” says Ford, “and he’s got a wonderful English sense of humor — dry, droll.” That drollery can get Daniels into trouble, as it did in September, when he told the Daily Mail, “What is funny is C-3PO looks the same — Harrison, Carrie, and Mark, not so much … Poor Mark. He was a young, lovely-looking lad when he was first Luke Skywalker, and now … well …”

Daniels tells me he meant no harm. “I’m very fond of Mark, and I actually love the beard,” he says, confirming the elusive Luke Skywalker’s new facial hair. “I regret the way some of the things I’ve said have been misinterpreted … I try to be realistic, to balance gently the good with the not so good. Otherwise, I come off Pollyanna: ‘Everything is awesome!’” He says the last bit in a goofy American accent he uses mainly to imitate journalists. “This sounds self-aggrandizing, but my sense of humor can confuse some people if their synapses aren’t …” Daniels has a flair for meaningful ellipses.

“There are times I have felt belittled,” he says. “And I think occasionally it makes me overly pretentious, clever, didactic. I want somebody to know I’ve got a brain. Most people are allowed to wear their brain on their face, but my face is hidden, and I do such a wacky job. People think, What an idiot, what kind of actor would do a performance like this? I like C-3PO, I’m very fond of him, and if anybody belittles him, they belittle me.”

And how important is C-3PO? In a sense, he is the most dispensable main character in the franchise — an arthritic diplomat in a world at war. Okay, he translates occasionally, but R2-D2 smuggles Death Star blueprints. Ewoks ambush the Empire in Jedi. Chewbacca throttles people. C-3PO mostly quavers and complains. And yet he is the engine of exposition and continuity, given the first line in A New Hope and the last in Revenge of the Sith.

He is also the last human robot. Descended from oversize vacuum cleaners with accordion arms, he gave way to the interchangeable CG bots of Attack of the Clones. But he survived alongside them (even exchanging body parts with them while uttering tragic lines like, “I’m quite beside myself”). The one constant in an evolving universe, he’s a literal relic, “a piece of the true cross,” as he puts it. “Each time I would appear on the set in full regalia, George would say, ‘Ah, now Star Wars has arrived.’” He is the droid we are always looking for.

Hurrying over to Daniels’s handsome Beaux-Arts apartment building, the one that neighbors the magnificent Georgian house, we return to the subject of his next-door life. “Would I like to be Benedict Cumberbatch onstage playing Hamlet? The responsibility night after night is huge, terrifying,” he says. “I know there are people who do these things way better than I do.” No regrets, then? “It’s always tempting to have regrets,” he says. “I would like to think that if that were the case, a second voice would come in. ‘Yes, but aren’t you lucky?’”

Four minutes before Australia and New Zealand kick off in the final, we enter the long foyer of Daniels’s home. Christine Savage, a former executive with an efficient blonde bob, offers beer and Parmesan crackers. She and Daniels married, after many years together, in 2013. Two neighbors, Geoff and Liz, come by in accidentally matching rugby shirts. Daniels cedes two modern white couches and sits cross-legged on the floor. He’s rooting for New Zealand, mainly because “we really liked it when we visited.” Two built-in bookshelves hold little more than Star Wars novelizations and travel guides.

The match is thrilling, especially when punctuated by joyous claps from Daniels. New Zealand wins with last-minute tries (rugby touchdowns) in both halves. The injuries are brutal, the players and fans incongruously polite. “Lots of fans come from public school,” Geoff explains, “what you call private school — educated. And rugby players are professional, doctors and people like that.”

Daniels is reminded of cosplaying conventiongoers. “One seminal moment for me was patronizingly saying to a group of stormtroopers, ‘What do you do when you’re not dressing up?’ One was a surgeon, and one of them was an oceanographer. After that, I shut up.” On our way to his building, Daniels had cheered early trick-or-treaters on the street, but then added, “I’m not a big Halloween person. I dress up for a living.”

In the apartment, there are precious few visible traces of that strange career. The décor is spare but eclectic — walls and fixtures stormtrooper-white, adorned with wall-mounted North African antique doors and muted modern paintings. The only Star Wars artifact is in a sitting room separated by French doors: a stocky, 18-inch yellow-brick Lego C-3PO.

That’s where, during halftime, Daniels takes a few more questions — “Keep them short, and I’ll try to keep my answers long.” Reportedly, I say, he’s made millions. “Who says I’ve made millions?” It seems perfectly plausible. “It’s not an extravagant life,” he insists. “We’re not here to talk about money, but if I appear in a commercial or a cartoon, yes, I get paid, because that’s my job.” But he doesn’t own the character. “In no way do I get a penny for every Lego brick that’s sold.”

Daniels dwells on the less tangible rewards of the franchise: security, recognition, belonging. Those, too, have appreciated over the years. “On group emails it now says ‘Team Star Wars,’ and that feels really good. Nobody’s ever used that term before.” Was there a single moment, I ask, when C-3PO, this golden cage that hobbled him for months and pigeonholed him for decades, became someone he could inhabit indefinitely? He traces an exponential curve in the air. “I recently watched Dr. Strangelove again, or: How I Stopped Worrying and Learned to Love the Bomb. What a way to put it. I have learned to love this. I’ve become attached to him, and I think he’s fairly attached to me. And as you can see” — he gestures around the room, encompassing the Lego robot and the other accouterments of his surprisingly uncluttered life — “there are benefits. A droid with benefits.”

*A version of this article appears in the November 30, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.