Herman Wouk has never been one for half-measures. His two-volume World War II saga, The Winds of War and War and Remembrance, ran to nearly 2,000 pages and was adapted into a corresponding pair of TV miniseries. His third novel, The Caine Mutiny, won a Pulitzer, spawned a Broadway play, and gave Humphrey Bogart a defining role of his career. Wouk’s meaty, breezy fiction (on the Navy, the Holocaust, Israel, Nixon, a starry-eyed Jewish girl who called herself Marjorie Morningstar) earned him millions of readers but precious few glowing reviews. Still, even as he aged out of both the cultural center and the typical human lifespan, the strict Orthodox Jew kept on writing.

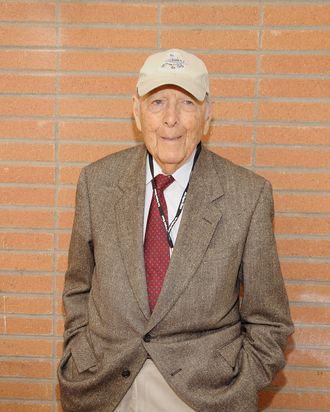

Last week, at the age of 100, he finally published a memoir — of sorts. Sailor and Fiddler skims his life story in two parts: “Sailor,” devoted to work and show business, and “Fiddler,” on Israel and religion. At 160 pages it’s shockingly brief by Woukian standards but, given his privacy, unusually candid. He writes for the first time about the early death of his firstborn son, but mostly sticks to the genesis of his novels and his distracting dalliances with pop entertainment (Broadway, Jimmy Buffett). Wouk used to decline all interviews, but old age seems to have loosened his tongue. He spoke to us via video Skype — why not? — from his book-lined office, wearing a loose shirt, a large yarmulke, a long and sparse beard, and a wide grin.

You’ve written nonfiction and autobiographical novels before, but what made you want to write your first memoir at 100?

I didn’t just decide to write an autobiography at this time in my life. Harboring a project for 20 years is not unusual for me at all. I thought that someday I might do something about it. Sailor and Fiddler was a title and nothing else; I tried to use it a couple of times but always found myself writing about the moment. Whatever this is, it isn’t about the moment. The first picture I had in mind was Sinbad the sailor, but, because as you know from reading the book, I hadn’t had a very adventurous life.

War, travel, fame, fortune — seems pretty adventurous to me.

That’s perfectly true, but in what sense was I a sailor? I was only at sea for three years during World War II, and after that I came back, married a gal, and became a writer. I’d started my career writing jokes with Fred Allen. Are you too young to be familiar with Fred Allen?

I’ve seen a few old clips of What’s My Line, including those you guest-starred in. Did your five years writing radio gags teach you anything useful for 1,000-page war sagas?

It didn’t help me in the least. It was a different set of values, attitudes. As a nice Jewish boy growing up in the Bronx, all I wanted to do was to make a living. And in the depths of the Depression, I ended up making $150 a week for writing jokes. That was then an awful lot of money, and I had a very pleasant youth, you might say. But I knew it was completely ephemeral. So did Fred Allen. He wrote this excellent book called Treadmill to Oblivion, and that’s what television is right to this day. If a man or a woman gets distinguished, they go up into pictures, although television has enormously improved. The British series in particular are exceedingly good. But that had nothing to do with me once I came back from the Navy.

You blow right past your childhood in this book, refusing to write about it “for love or money.” But you also say a lot of it was lifted straight into City Boy, your second novel.

My boy’s book, as it were. I was going against the tide because, at the time, James T. Farrell and others were writing very violent books about childhood. Well, I had a very relaxed and pleasant childhood up in the Bronx. We spent a lot of time out in open spaces on the banks of the East River. It was not intended to be anything other than my homage to Mark Twain. He had a tremendous effect on me. My mother bought this set of Mark Twain books because the bookseller said, “This is the American Sholem Aleichem.” I found these volumes and started to read them, and now they would call it an epiphany. Now I knew what literature was, where I wanted to go, what I wanted to do with my life.

Do you ever think about whether you’ll have a reputation after your death — that in 50 years some child will read Caine and think, That’s literature?

I could quickly say almost not at all. Let me elaborate on that. Of course you want to last, but I think it was Twain who said no one knows what you’re worth until 30 years after you’re gone. And Stendahl said every novel was a lottery ticket for 100 years from now when the payoff comes. If you’re a serious writer you don’t worry about that — you write the books the way you feel; you write the things you see. I don’t know if they’ll be around 50 years from now. I hope so. I think it. As you know well, critics are divided on my work, but they all seem to agree, at the worst, that Winds of War and War and Remembrance are a very good popular history of World War II. That in itself is a chance for hanging on for a while.

How did you celebrate turning 100?

I wasn’t very interested in celebrating it, but my son lives here in Palm Springs, and my staff was all for a big hoo-ha. So we ended up having a lunch and a nice cake in the most middle-class possible way. Members of my synagogue came in and danced around a bit, and then I went back to work.

Work? In Sailor and Fiddler you said you were done writing.

It’s a rhetorical flourish as it were. I’m always working, as long as my health allows it. It may not cohere into a book, but it might. I don’t care that much. This is a story that I like to tell and I’d like to believe it’s true: Faulkner was also a very reclusive guy; he gave very few interviews, but he went to his daughter’s high-school graduation and spoke to the girls. One of them asked him, “Do you write on a regular routine?” He said, “Well, as a matter of fact, I can write only by instinct. I’m just very fortunate that instinct strikes me every morning at a quarter after nine.” So for me it’s about the same.

I’ve seen you referred to as a recluse.

Well, I don’t think of myself as a recluse, but on the other hand I don’t search out interviews like this. This was represented to me as something I should do. Although I’ve been very uncooperative earlier in my career, here’s a book that I’ve written at 100 years old, and I don’t know if anyone wants to read it, so well, okay, and here we are. When I started I was very eager to get interviews, and then I found out what interviewing was, and I thought, This isn’t for me.

What was your main complaint?

Invasion of privacy. That’s what it is, you know. You’re sitting there in New York and talking to me out here, and Skype has just made it worse.

I can only see a little piece of your office right now.

That’s perfectly true, but you can ask me about a lot of things.

Speaking of which, what made you decide to write, for the first time, about your son’s drowning at 4 years old?

That’s a hard question to answer. When I came to that part of my book it was something to do, something to say, there and never before and never since. I don’t know. I just wrote it there because it seemed right. It’s a darker note in a light book. I tend to work the sunny side of the street, some would say. And I know how dark the world is.

You have written at length about Auschwitz, after all, in War and Remembrance. But it seems Marjorie Morningstar, about a Jewish girl’s coming of age, is the book younger generations are still talking about. What if that’s the one that endures, rather than the war books?

If one of my books is remembered at all, I’ll settle for whichever it was. Marjorie was kind of a technical exercise, though of course it is much more than that. Henry James’s technique of putting you inside one person’s head and holding it there, while everything’s happening around that person, is striking. Here’s a book where, from the first chapter to the last chapter, the reader is inside a growing girl’s head — which can be rather a dumb place to be, but there you are. Everything that happens in the world occurs through this young girl’s head.

David Frum argued recently in The Atlantic that your unpopularity with critics is due to your conservatism and support for the Establishment.

I don’t think much in terms of criticism. I only wrote one book review in my life. When I finished my first book, here I was an author, now what? I talked to my editor and he said, “I’ll talk to Rita Van Doren,” who edited the book-review section of the New York Herald Tribune. She gave me a book to review, and it was about the radio business. It was atrocious. I mean, it was a wonder to me it got published. As a writer, I just couldn’t be mean about it. Whatever I wrote was kind of on the indulgent side, and I just let it go at that, and I felt completely dissatisfied. In my case, in midlife I said, “To hell with this stuff.” Now, I’ve always called myself an FDR Democrat. Even in college, we’re talking about the middle ’30s, the hot thing was to be a Communist. My attitude toward the liberals, so-called — they were never very deep thinkers — was total irony. What they’re saying is very unconvincing in the way it’s told, shrill, uninterested in other views, and all that kind of thing.

You call yourself a “cheerful centenarian” in Sailor and Fiddler. What does that mean?

Well, centenarian needs no explanation. It’s cheerful that requires some … Well, setting aside the infirmities that come with it, it’s a great time of life. I wake up every day and I’m thankful to the Lord. I’ve arrived here, four arms and legs, eyes still working, ears still working. That there is a reason to be cheerful if one thinks about it. As for the infirmities, that’s part of the game. You’ve got to pay, and what you pay on the way out depends on how far you go, I guess, to see how long the coupon will last. It’s very hard to be cheerful nowadays if you want to get to the depth of it. I have a grandson who’s very concerned about sustainable development. Everybody realized that we really do live not on a platform which is infinitely big. It’s a really very, very small place. For those who think about it, it’s very sobering. In any case, it’s not a question of forcing good cheer. It’s a person’s nature. My grandfather had three sons and two wives die of typhus in the old country, and he was probably the most cheerful man I knew in all my life.