The culminating scene in Sunday night’s premiere of Vinyl centers on the collapse of the building housing the Mercer Arts Center, a music-and-theater venue in Greenwich Village. It seems too good to be true, a metaphor for the vibrant-but-rotting city of 1973 and also the vibrant-but-rotting life of the lead character, a record executive named Richie Finestra.

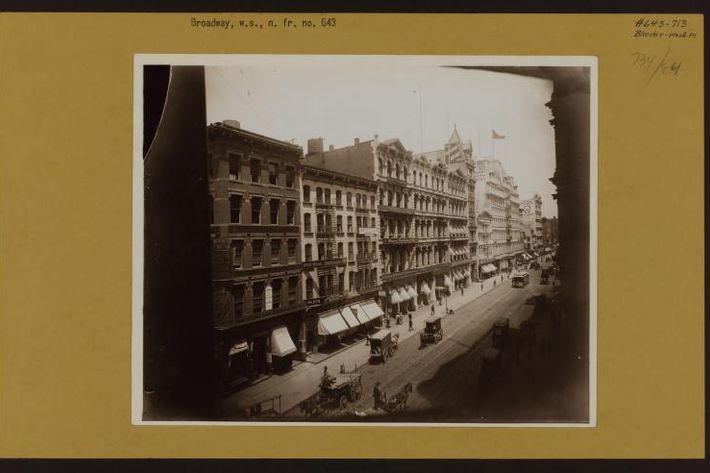

And although the screenwriters of the pilot (including Martin Scorsese, who directed and co-wrote it) have bent a few details slightly to suit the story, it’s no fiction. The Mercer Arts Center, and the eight-story building housing it, was a very real place at Broadway and West 3rd Street that collapsed, in a very real cloud of dust, on the evening of August 3, 1973.

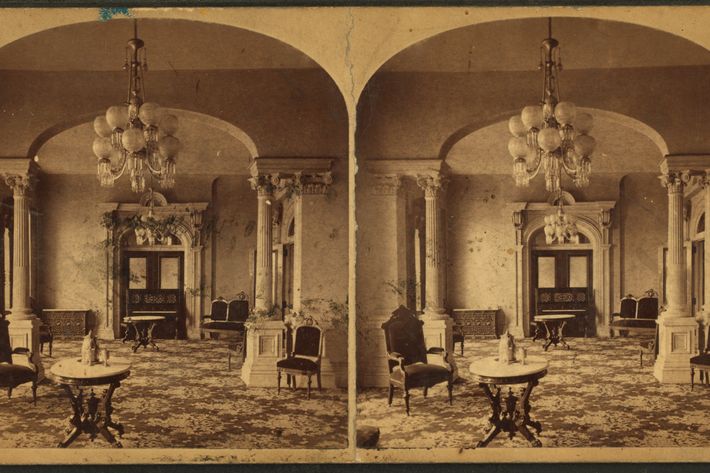

Like a lot of things in New York in the early 1970s, the building was a wreck, living on borrowed time. In the early 1870s, by contrast, it had been one of the city’s great hotels, called the Grand Central.

With eight marble-faced stories and 600 rooms, it was a huge structure, going clear through the block from Broadway to Mercer Street with entrances on both ends. (For a sense of what it looked like, stop by the Grand Hotel, which still stands at Broadway and 31st Street, and was built by the same architect for the same owner.) Within a couple of years of its opening, the Grand Central Hotel gained notoriety after a prominent gent, financier James Fisk, was shot in a second-floor corridor, apparently due to a love triangle. (The killer, Edward Stokes, went to Sing Sing.) But the hotel had better days, too: The National League was founded here at a meeting of baseball-team owners in 1876. Diamond Jim Brady was a regular guest.

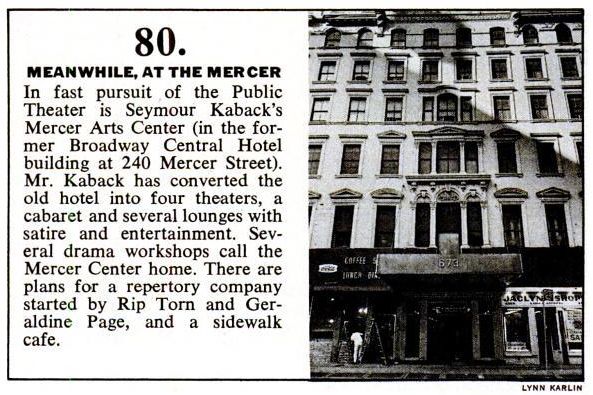

As often happens with aging hotels, the Grand Central slipped from luxurious to utilitarian. It later changed its name to the Broadway Central, housing servicemen during the Second World War. By the 1960s it was a well-known dump, a welfare hotel where small crimes seemed to happen constantly. (Among other things, 30 small fires broke out there, or were set there, in just three years.) It was renamed again, now the University Hotel, with an eye toward reinvention. In 1971, a theater impresario named Seymour Kaback rented the decrepit public rooms and catering areas and remodeled them, tucking in four theaters plus some lounges and a cabaret, and calling it all the Mercer Arts Center. An experimental-arts workshop in the old hotel kitchen was called the Kitchen.

The Mercer Arts Center was not without successes. The Effect of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds, by Paul Zindel, had its New York premiere here in 1970, won the Pulitzer Prize the next year, and might have kept running indefinitely except the theater leaked so badly, the production had to move out. It was a music venue, too: Charles Mingus played the cabaret room, and the New York Dolls, who are on stage when Richie arrives at the Mercer in Vinyl’s premiere, performed here regularly. (Marlene Dietrich is said to have shown up to see them one night. Just imagine that: Weimar glamour gal in gone-to-hell Victorian hotel watching boys in eyeliner and heels play punk rock.) This very magazine suggested that Kaback was giving Joe Papp’s Public Theater a run for its money.

Still, the Mercer was in a very crummy building, and some questionable renovations decades earlier had silently but seriously weakened the structure. Kaback knew something bad was coming, too — for months, he’d been reporting fresh cracks and alarming bulges in the walls, and after a bunch of foot-dragging, the city had issued some violations. On August 3, 1973, the day of the collapse, Kaback saw bricks fall and heard beams groaning, and over the course of the afternoon he began sending up flares to everyone: the hotel’s owners, its manager, the Buildings Department. “We were expecting 2,000 people that night,” he later told the Times. At about 5 p.m., as the signs grew more ominous, Kaback himself bolted, then ran back in for his wallet, and got out just in time. The south section of the building came down at 5:10 p.m. (In Vinyl’s CGI version, it happens late at night as the Dolls play, and the feeling is that sheer guitar power causes the collapse.) About 300 people got out in time. Four were killed.

Today, an NYU Law School building occupies the site. But two traces remain. As the blogger Keith York City points out at the top of this excellent post, you can still see out the tar outline of the Grand Central Hotel’s mansard roof on the building next door, just as you can in the photo above. And the Kitchen survived the collapse, two moves, and a Hurricane Sandy flooding, and has kept on cooking, now far away on West 19th Street.