Are Batman and Superman allies or rivals, at their core? They’re definitely not enemies, and that’s only partly because they’re both superheroes. For long stretches, particularly when the characters were new, they had a deeply chummy relationship, with Batman like a non-superpowered Superman — a lesser, but cheerful, do-gooder who also fought for truth, justice, and the American way. (It was kind of adorable, with Batman almost acting like a kid who smilingly looked up on his star-athlete older brother.)

And yet, for the past 30 years, the relationship has been punctuated by a series of spectacular fights — a gruesome tussle over ideology in 1986’s graphic novel Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, a dramatic dust-up due to mind control in the 2003 comic-book story line “Hush,” and, of course, an upcoming gladiator match in this weekend’s big-screen tentpole Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice. At this point, nobody really remembers that early, sunny friendship — when it comes to superheroes, pure friendship’s boring. Batman and Superman are both, of course, good guys, but what we so often want to see is them fighting.

But why? Why are fans so desperate to see superheroes in conflict that they urge superhero writers to employ absurd narrative contrivances like mind control or alternate universes to make happen what would otherwise be vanishingly unlikely fights (a tactic used well over a dozen times in the history of Batman-Superman tales)? One big answer is no answer at all — who wouldn’t want to see them fight? Every comics geek’s inner adolescent is perpetually asking, What’s the point of having two heroes if you aren’t also going to game out who’d win? As comics critic Chris Sims put it in a column on the topic, “When you have characters and all you see them doing is winning, it’s natural to wonder who would win harder if they ever had to compete. For that question, Superman and Batman make the perfect contenders.”

But we also want to see them fight because, to an unusual degree even for comic books, the fights mean something. That is, they are about something — or some things. Namely: how to make a better world, with Superman operating through hope and inspiration, and Batman through fear and intimidation. As the villain Lex Luthor puts it in the new movie, it’s “god versus man, day versus night.”

Let’s start with “god versus man.” Superman is an alien — which is to say, celestial — creature, born on another planet but here completely alone, completely singular in his powers, which have at times included feats like reversing the spin of the Earth to turn back time. Batman is not just a man but a broken one, who inhabits a broken universe, his parents killed by a petty criminal and raised in an era of rapid urban decay — “an old-money billionaire, a human, an orphan who has seen the worst of the world and let it all but turn him to stone,” in the words of critic Meg Downey. Superman, by contrast, “is a farm boy, an alien, raised with a stable adoptive family, who has seen the worst of the world and let it teach him a profound sense of empathy.”

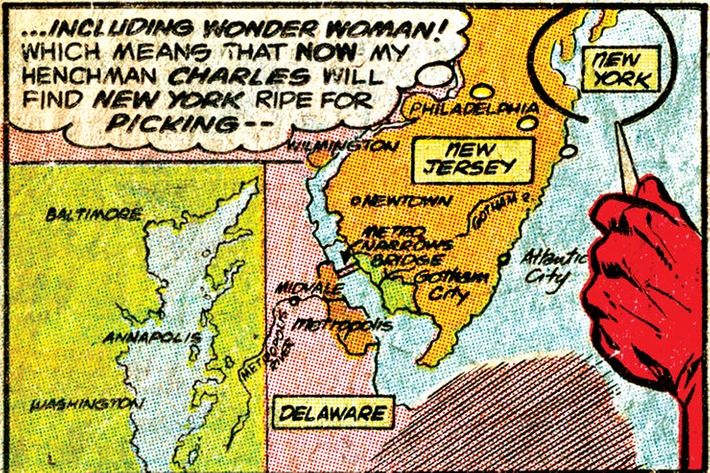

Which leads us to “day versus night.” Superman has faith that humanity will tend toward goodness if you give it trust and hope; Batman lacks that faith and believes the world only gets in line if you grab it by the throat and never let go. The former spends his contemplative moments hoping for the best; the latter spends those moments vigilantly preparing for the worst. But this contrast isn’t just characterological; it’s also historical. The icons were created almost simultaneously, but Superman is unmistakably a figure of his early years — the 1940s and 1950s, an era of buoyant, blinkered wartime and postwar consensus (at least as it might have been felt by most white, boyish comic-book readers), when it seemed appropriate to deploy a godlike do-gooder to do things like help cats out of trees or return purses to de-pursed Metropolis women. (One of his early nicknames was the Man of Tomorrow, after all.) Batman came of age later, beginning in the 1970s, the era of American malaise and urban decay, using cynicism as a weapon for good and training his sights on a Gotham City so broken it often looked like a war zone (often fighting super-criminals who hoped not just to plunder the city but overturn any lingering faith its denizens had in the virtue of compassion and social order). Which of these two worldviews provides the better way to live a good and productive life? You can do both, of course — just as you can love both characters and write them in such a way where they get along with one another. But readers don’t just want that — readers want to see the conflict.

And, in a real-world sense, most of them are on one side. Today, Batman is a far more popular character than Superman, and he typically wins whenever they go toe-to-toe in a story — which is, of course, ridiculous, considering he’s just an earthling, but that only makes it all the more remarkable as a reflection of reader preferences and prejudices. Outside of comics and movies, too, his worldview predominates, in the form of a perennially apocalyptic vision of the near future. In all ways, Batman is winning in the battle of Batman vs. Superman, which is especially strange given how little New York today, say, looks like the Gotham of The Dark Knight Returns. But we’ve been living so long in Batman’s universe that it can be hard to remember his worldview didn’t always have the upper hand.

They began as friends — almost as doubles. Superman was created by Cleveland cartoonists Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster and debuted in 1938 in the pages of Action Comics No. 1. At first, Superman only barely resembled the big blue Boy Scout we know today: He smirked while punching out slumlords, domestic abusers, and loan sharks and he seemed relatively unconcerned with preserving individual human life. He was, as Superman historian Glen Weldon puts it in his exhaustive and fascinating Superman: The Unauthorized Biography, a “bully for peace.”

He was also an instant sensation. DC Comics knew it had a hit on its hands, but wanted a bigger one — which means they needed their star to be as family-friendly as possible. As comics historian Gerard Jones recounts in his chronicle of the era, Men of Tomorrow: Geeks, Gangsters, and the Birth of the Comic Book, DC exec Jack Liebowitz saw the nascent Man of Steel as “something that could be built and sustained here, a kind of entertainment that kids liked better than pulps and would continue to if given reason to keep coming back.” Accordingly, in 1940, he and editor Whitney Ellsworth drew up a pristine code of conduct for superheroes that, among other tenets, forbade DC heroes from knowingly killing. It was not unlike the onset of the Hays Code in Hollywood, and by the time U.S. soldiers were being sent off to war in 1942, Superman had become cheery, lovable, and status quo-respecting.

Those were not adjectives you could use to describe the initial depictions of Batman. He was first published in DC’s 1939 comic Detective Comics No. 27, the creation of Bob Kane and Bill Finger. At first, he was a “weird figure of the dark” and an “avenger of evil,” as one of the early stories put it. Unlike Superman, he had no special powers other than being exceedingly wealthy. He was more or less a rip-off of pulp hero The Shadow and spent his time in the darkness, attacking — and occasionally even murdering — evildoers. But, like Superman, he was also an instant smash — which meant the same image-buffering fate. In his new history of Batman, The Caped Crusade: Batman and the Rise of Nerd Culture, Weldon tells of newspaper editorials and church bulletins railing against dark, violent comic books.

As a result, the editorial leadership pushed Batman out of the shadows, making him brighter and poppier, and even turning the weird loner into a kind of doting father figure to a scrappy young ward named Robin (a relationship that could’ve really gotten dark and weird in different hands). “Adding Robin was no mere cosmetic tweak,” writes Weldon, “it was a fundamental and permanent change that placed Batman in a new role of protector and provider.” He stopped killing. He worked cheerfully with the Gotham police. He walked around in broad daylight. The Batman and Superman brands were more or less in sync.

Of course, Superman was a much more natural family-friendly sell than Batman, because comics writers couldn’t quite eliminate all of the darkness from the character of the Dark Knight, as later they’d have trouble trying to turn Superman into something approaching an antihero: One of these characters was a benevolently powerful space-god, the other a weirdo orphan wearing bat ears. This probably, at least in part, explains Superman’s bigger stature through the 1940s — his persona was a near-perfect vessel for imperious American confidence and social order. But Batman had his clean-cut pitch, too: He may not have had superpowers, but he was a kind of icon of self-improvement, since he had willed himself to reach the peak of human physical potential (well, willed and spent) and had fought a delightful gallery of enemies.

Oddly enough, it took DC a long time to figure out that these guys were two great tastes that could taste great together. Superman and Batman first appeared in an image together on the cover of a 1940 promotional tie-in comic for that year’s World’s Fair, but the interior pages showed no story where the two of them interacted. In 1941, there was a comic in which they stood side by side to help with a fund-raising drive for war orphans, but they had no dialogue with each other. That same year, they started appearing alongside one another on the covers of a new comics series called World’s Finest, and on those covers, you saw them wordlessly playing baseball or going skiing — but once you opened the comic, you saw no stories where they actually hung out.

Superhero fiction has been a trans-media enterprise for longer than many give it credit for, and the genius notion of having Batman and Superman actually solve crimes together — as opposed to just convention-bid in tandem — apparently didn’t materialize until a 1945 episode of Superman’s spin-off radio show, The Adventures of Superman. Their first printed co-narrative came in Superman No. 76, published in 1952. There, Bruce Wayne and Clark Kent — who had no knowledge of each other’s secret superhero-ing — found themselves in the same cabin on a cruise ship. When some criminals start a massive fire, Bruce turns out the cabin’s light to change into his costume, and Clark takes the opportunity to do the same. But suddenly, they get caught in the act by light from the flames passing through the porthole. “Why — why, you’re Superman!” Batman exclaims. “And you, Bruce Wayne … you’re Batman!” Superman counters. “No time to talk this over now, Superman!” Batman says as they rush out of the cabin.

Their ensuing adventure set a template for the way they’d interact for the next 20-odd years: They complete each other and accentuate each other’s different power-sets while having the same squeaky-clean tone and goals. Readers rarely saw a true ideological conflict between the two, and Batman subscribed to the Superman-ish notion that good can always triumph over evil, so long as we live clean lives and partner up with fellow do-gooders. The only difference between them was their skill sets. “They had Batman be the master technician and Superman be the big jock,” says Weldon. “Batman would be the ultimate brain and Superman would come over to Gotham for help on a case because It’s just too hard for me to figure!” Occasionally, the two would have friendly contests (for example, No. 76 saw them performing feats of strength to win their respective cities the right to host an electronics convention), and they would occasionally challenge each other for the betterment of each (in No. 149, Batman and Superman each use an amnesia machine on themselves so they can try to re-discover each other’s secret identities).

There were also real conflicts, though typically they unfolded under odd circumstances. “The logic of that time was heavily driven by covers,” says comics historian and longtime DC executive Paul Levitz. You wanted to grab lucrative young eyeballs with insane vignettes on the front of a comic book and “two heroes fighting was a classically successful cover.” The story on the inside was of secondary importance, largely built up to satisfy what was on the front. Irwin Donenfeld, the executive vice president of DC throughout much of the late ’50s and early ’60s, was particularly fond of this tactic, so you got nutso covers like that of World’s Finest No. 109, in which a flying (!) Batman throws a massive cinderblock at Superman while a horrified Robin gazes at them and thinks to himself, The sorcerer’s spell that’s been cast over Batman is forcing him to fight Superman — and now he has super-powers to do it with! Such stories satisfied a fannish desire to see the two fight, but what made them even more exciting was how perverse they were — there’s no way, after all, that these two would ever really have a problem with one another, right? And, whatever the fun of seeing them fight, you never had to worry too much about a permanent rupture: There was always some wacky explanation, like mind control, mistaken identity, or simply explaining that the tale was an “imaginary story,” wholly removed from normal continuity. The chummy status quo would always return by the next issue. The gods were in their heaven, all was right with the world.

It was only in the ’70s and ’80s that Batman truly emerged from Superman’s shadow, and it’s hard to avoid the impression that the Dark Knight was a product of that time (just as Superman was a product of the mid-century). This was a period shadowed by the assassinations of two Superman-like symbols of hope — Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr. Cities from coast to coast erupted into vicious race riots. A sitting president was tied to an insidious crime and resigned on live television. We lost a war for the first time and the economy skidded into an oil-slicked slowdown. At the cinema, audiences wanted heroes that were less like John Wayne and more like Dirty Harry.

In comics, they got one. For the first time since that brief window of grim violence in his earliest stories, the Dark Knight was dark again. That was a real reversal, given the deep, Technicolor imprint left by the ’60s Batman TV show, which may be the clearest depiction of the soft-focus Batman of the Superman era (what could possibly have been at stake in that always-sunny playhouse Gotham?). The Batman comics, in a bid for brand synergy, got similarly goofy. But viewers grew tired of the show quickly, turning it from a brief hit into a canceled failure and cultural punch line and spawning a wave of angry fan letters asking DC’s higher-ups to revise the character. One such letter, published in the pages of Batman No. 210: “Batman is a creature of the night. [He] prowls the streets of Gotham and retains an aura of mystery,” it read. “Get the super-hero out, and the detective in!”

Batman comics were ailing in sales, so DC’s leadership was willing to give it a shot. Under the guidance of editor Julius “Julie” Schwartz, upstart writer/artist team Denny O’Neil and Neal Adams were put in charge of Batman. As O’Neil recalls it, “I walked into Julie’s office and he offered me Batman like this: ‘We’re going to keep publishing Batman, obviously, but we’re not gonna do the camp thing anymore. Whaddaya got, my boy?’ What I thought was this: we’ll go back to 1939.” O’Neil looked to Batsy’s grim origin story for inspiration: “You’ve got this dark guy who’s seen his parents killed and he spends his life symbolically avenging that death,” he says. “That version of Batman seems to be the one that’s right.” O’Neil and Adams opted to have Batman scowl instead of smile, go out in the darkness and eschew the light, and meditate on how few people he could truly trust. “Superman has more faith in the system,” says comics critic Ardo Omer. “Batman was created because the system failed him and continued to fail Gotham.”

Batman was a much more natural icon of 1970s angst and anomie, but the darker turn in comics also came to Metropolis, where Superman’s virtues — once taken as self-evident — were being questioned in his own stories. O’Neil was brought on to write Superman tales, too, and felt it was no longer interesting to read about a perfect man who did only good. “The essence of fantasy melodrama is conflict,” O’Neil says. “You’ve got a guy who, at his strongest and most powerful, could blow out a sun! How are you going to create conflict for that guy?” DC’s leadership agreed. Through various in-story machinations, his powers were weakened for a while. But more important, doubting Superman became the order of the day. A 1972 tale penned by Elliot S. Maggin was boldly titled “Must There Be a Superman?” and saw the Man of Tomorrow realizing that he can’t fix structural problems like poverty and oppression. “You stand so proud, Superman,” read the opening narration, “in your strength and your power — with a pride that has found its way into the soul of every man who has stood above other men! But as with all men of power, you must eventually question yourself and your use of that power.” Wait, were we talking about Kal-El of Krypton, or the United States of America?

As Americans began to distrust power, so too did Batman begin to distrust Superman. They still fought side by side in the pages of World’s Finest and on the roster of DC’s premier super-team, the Justice League, but there were cracks in the façade. In 1973’s World’s Finest No. 220, written by Bob Haney and drawn by Dick Dillin, the two are trying to crack a case, and the Kryptonian is turning up his nose at their villain’s quest for “illegal revenge.” “I can understand revenge,” Batman says with a condescending scowl. “I took it myself against Joe Chill, my parents’ killer! It’s a human emotion — revenge! Trouble with you, friend, is you’re not human!” The ticked-off Superman punches a tree and asks, “Who’s not human!?”

An ascendant Batman and Batman-ist worldview made concrete conflict almost inevitable, and matters came to a boiling point in 1983’s Batman and the Outsiders No. 1, written by Mike W. Barr and drawn by Jim Aparo. During a meeting of the Justice League, Batman declares that he’s had enough of the Superman-led squad’s law-abiding approach to saving the world. He says he’s going to break international regulations to rescue someone and when Superman tries to stop him, a furious Batman slaps his old friend’s hand away and says he’s resigning. Superman tries to appeal to the better angels of Batman’s nature: “We’ve always served as an example to the others —” But the Dark Knight cuts him off. “I never asked for that, Superman!” he barks. “I never wanted men to imitate me — only fear me!”

Nowhere was their ideological conflict more pointed than in the most famous Batman story ever told, which is also the greatest Batman-Superman fight story ever told: writer/artist Frank Miller’s 1986 masterwork The Dark Knight Returns. It’s a dense tale set in a dystopian Gotham City tattooed with graffiti and beset by violent youths. Miller had been living in New York during its Koch-era nadir, getting mugged and seeing the tabloids scream about urban decay and the vigilantism of men like Bernhard Goetz. When Miller was commissioned to write a Batman tale, he decided to make Bruce Wayne what he called a “god of vengeance”— a pretty good description of Dirty Harry, actually, or other iconic antiheroes, like Travis Bickle and Rambo, who had already passed into American myth. “If he fights,” Miller wrote in his notes for Batman, “it’s in a way that leaves them too roughed up to talk.” His ideal Batman “plays more on guilt and PRIMAL fears.”

The result was, indeed, steeped in primal fear. In The Dark Knight Returns, an aging Bruce comes out of retirement and goes on a Death Wish-esque crusade to clean up the streets by any means necessary. He has also come to hate the sunshiny outlook of Superman, a figure who — in Miller’s depiction — has a naïve faith that it’s morning in America. Miller’s Superman has made a Faustian pact with the government, taking orders from President Reagan. (Well, he’s not technically called Reagan, but any reader will recognize the fictional commander-in-chief’s wrinkled smile and folksy chatter.) “I gave them my obedience,” Clark thinks to himself while destroying some Soviet weaponry. “No, I don’t like it. But I get to save lives — and the media stays quiet.” When Batman leads an army of vigilantes during a night of chaos in Gotham, Superman is ordered to take down his erstwhile ally.

The fight that followed was the most perversely inventive one in the canon. Superman arrives in Gotham and Batman completely beats the shit out of him. As it turns out, Superman may be strong, but Batman has two advantages: wealth and paranoia. His distrust of the Metropolis Marvel led him to come up with a cunning plan in preparation for the battle, and he can throw as many toys into it as he likes. He fires missiles at Superman; he wears a massive battle-suit that he plugs into the city’s electrical grid, then punches Superman hard; he has a pal hit the Man of Steel with some synthetic Kryptonite (Superman’s historic weakness); and he ultimately wins, knocking Superman to a standstill. All the while, he takes pride in hurting Superman and meditates on their differing worldviews. “You sold us out, Clark,” he thinks to himself. “Just like your parents taught you to. My parents taught me a different lesson — lying on this street — shaking in deep shock — dying for no reason at all — they showed me that the world only makes sense when you force it to.”

A similar exchange punctuates writer/artist John Byrne’s miniseries The Man of Steel, another influential recast of the Batman-Superman relationship, published the same year as The Dark Knight Returns (though less well-known). Issue No. 3 chronicled a wholly rebooted version of the heroes’ first meeting, devoid of the charming cruise-ship meet-up. Instead, the two of them, early in their careers, join together to catch a criminal — but they immediately question each other’s approach to the task. Batman beats up a lowlife thug in an alleyway for information; Superman finds Batman right afterward and calls him an “outlaw” and an “inhuman monster.” They decide to focus on taking down the villain, and, as they part ways, they reach a tense détente. “Well, I still won’t say I fully approve of your methods, Batman,” Superman says, flying away, “and I’m going to be keeping an eye on you, to make certain you don’t blow it for the rest of us … but good luck.”

But let’s get back to The Dark Knight Returns. “In political terms, Superman would be a conservative and Batman would be a radical,” Miller said when I interviewed him a few months ago. Miller himself identifies as a libertarian, so his protagonist’s distrust of power makes all the sense in the world. But the political question of the book is, in my view, only a symptom of a larger philosophical matter. This Batman is utterly without faith in anything beyond his immediate control. Sure, he can trust his butler, his sidekick, and his weaponry — but that’s about it. Everyone and everything else needs to be throttled and bent into shape, in order to wrestle with a world otherwise almost beyond repair. What’s more, Batman hates Superman because Superman does have faith: faith in the government, faith in Reaganite prosperity, faith that Batman might be able to see reason and give up. In Batman’s eyes, these are failings.

No one had ever before attempted to show these two being in such opposition, and so filled with bloodlust. But the crazy experiment was a massive success. For the first time, Batman comics started consistently outselling Superman ones, but the transformation went beyond mere sales. “It’s difficult to overstate the influence The Dark Knight Returns has had on comics and the culture that has risen around them,” Weldon writes. Thanks to Miller, the vision of Batman as a pitch-black bruiser and schemer was carved into the rock of superhero fandom. In 1989, Tim Burton’s Batmanhit theaters and, while it lacked the deep gothic mood of later screen hits like the influential Batman: The Animated Series and Christopher Nolan films that followed, it offered many of the dark, angry pleasures that Dark Knight Returns had surfaced — and it was a box-office smash unlike anything a DC character had ever seen.

Very few tales since then have dared to put the two heroes so viciously at odds as they were in Dark Knight, but every story of conflict since is shadowed by Miller’s and Byrne’s characterizations. In 1988’s Batman story line “A Death in the Family” — written by Jim Starlin and drawn by Jim Aparo — Robin is brutally murdered by the Joker and a complicated diplomatic situation makes any Bat-revenge legally tricky. Clark flies in to tell Bruce to stay in line: “There’s nothing you can do here,” he says. Bruce fires off a massive punch to Clark’s jaw, which of course doesn’t even bruise the Man of Steel. “Feel better now?” Superman asks, frowning.

Even when they got along, after Dark Knight, there was often a steely sense that things could go awry between them. A 1990 Batman-Superman crossover story called “Dark Knight Over Metropolis” dealt with the theft of a ring made out of Kryptonite, and at the end, Supes opts to give the ring to Batsy for safekeeping, just in case someone evil ever takes over Superman’s mind and he needs to be taken down. “I want the means to stop me,” Clark says, “to be in the hands of a man I can trust with my life.” It’s a sweet moment, but also a grim one. Indeed, for all the talk of trust, Superman was dourly preparing for the worst and acting out of fear. In other words, much as Batman had acted like Superman in the middle of the century, we had somehow entered a world where Superman was acting like Batman.

Perhaps more important, the Batman mentality — paranoid, fatalistic, violent — was setting the pace for superhero fiction generally. Superman was killed by a rampaging monster in 1992. One year later, a brutal villain snapped Bruce Wayne’s spine, and a younger, more vicious successor took over the Bat-mantle. Superman came back from the dead and the original Batman took back the cape and cowl, but they still fought increasingly apocalyptic threats that required harsh pragmatism to beat. The best-selling comics across the industry in the early- to mid-’90s were violent and oozing with themes as dark as the colors. America wasn’t as decrepit and frightening as it had been in prior decades, especially in its cities, but in an age of increasing cynicism, Batman felt far more au courant than the Metropolis Marvel. As a new century dawned, conflicts between the two became more frequent in comics and, in nearly every one, Batman kept winning.

There was 2000’s Justice League story line “Tower of Babel,” written by Mark Waid and drawn by Howard Porter, in which we learned that Batman had detailed and brilliant plans to take down every member of the League, just in case — including Superman. There was the 2003 alternate-history tale Superman: Red Son, written by Mark Millar and drawn by Dave Johnson and Kilian Plunkett, which imagined a world where Kal-El of Krypton landed in the Soviet Union and became a Stalinist dictator — only to be challenged by an anarchist Russian Batman who uses his superior wit to knock the snot out of Soviet Supes before killing himself with a suicide bomb. There was that same year’s Batman No. 612, written by Jeph Loeb and drawn by Jim Lee, where Batman uses that old Kryptonite ring to knock a mind-controlled Superman onto his butt. There were 2014’s Batman Nos. 35 and 36, written by Scott Snyder and drawn by Greg Capullo, wherein Superman gets mind-controlled yet again and Batsy spits a tiny pellet of Kryptonite-like material into Supes’s eye to put him down. “Who wins in a fight?” Batman muses to himself in that last story. “The answer is always the same. Neither of us.”

It’s a nice rhetorical flourish, but in the real world, Batman iswinning. Not only do creators nowadays think stories work better when he comes out on top, but he also outsells Superman on the comics stands and — much more important — at the box office. Way back in the earliest days of big-budget superhero filmmaking, 1978’s Superman: The Movie was a sensation — but its sequels showed massively declining returns and that incarnation of the franchise was canned after 1987’s loathed Superman IV: The Quest for Peace. Two years later, Batman struck big with the aforementioned Burton flick, which got two hit sequels: 1992’s Batman Returns and 1995’s Batman Forever. The failure of 1997’s Batman & Robin put DC Comics-based movies in the wilderness for a while, but it was Batman who led them back to the Promised Land. Christopher Nolan’s Batman Beginshit theaters in 2005 and was a surprise critical success, but the real action came with its two sequels. The Dark Knight and The Dark Knight Rises each made more than a billion dollars worldwide — numbers that were unthinkable for a superhero flick just a decade earlier. As many film critics noted, in the age of the War on Terror, this Batman seemed to be the hero we deserved.

Superman, on the other hand, couldn’t get airborne. Bryan Singer’s Superman Returnshit theaters in 2006 and it was as sunny, colorful, and hopeful as you’d want a Superman story to be. But Warner Bros. was disappointed in its performance and cancelled plans for a sequel. After years of failed proposals, a new Superman movie finally hit theaters in 2013: Zack Snyder’s Man of Steel. It was a hit, raking in $668 million worldwide and giving Warner the confidence to use it as the starting point for its new DC Comics-based “shared universe” of interconnected films, the next of which is Batman v Superman. But at what price to his soul did Superman get this box-office victory? Man of Steel is a very dark movie. The visuals play out with gritty, color-drained filters. Superman spends much of the movie moping over a dead parent and wondering what the point of everything is. In the end, he has a horrifically violent battle with a fellow Kryptonian that levels Metropolis. He even grimly concludes that the only way to end that fight is to kill his rival (something the comics versions of Superman and Batman never do). The whole endeavor shows us a Superman who is brooding, angry, and pessimistic. In other words, it seems like the only way to do a successful Superman movie is to make it feel like a Batman movie. With Batman v Superman, they’ve just made another one.

The Batman perspective has some things going for it, of course: The world can indeed look pretty dark, as our collective anxieties and casually apocalyptic political mood testify daily. But it is also not the 1970s or ’80s anymore, and new threats like ISIS and climate change aside, the urban hellscapes which gave rise to the Dark Knight are distant memories at this point. Which does make you wonder: How much is the cynicism of Batman a logical response to a terrifying future, and how much a self-perpetuating worldview with a locomotive logic of its own? And then there’s the cost to comic-book narrative: If Batman and Superman are going to keep fighting, could we maybe let the Man of Steel win? Because if the political worldview of superhero fiction is going to hang in the balance with each battle, the least we could ask for is a little genuine suspense about which one of the do-gooders is going to come out on top.

*A version of this article appears in the March 21, 2016 issue of New York Magazine.