The Story

American Crime Story: The People v. O.J. Simpson, the pulpy series that airs its finale tonight, can’t possibly re-create one thing: the degree to which the Simpson trial intruded into Americans’ lives. Because it was broadcast live, and streaming was way in the future, offices ground to a halt every time the news took a major turn as people sought out the nearest television.

On October 3, 1995, everyone did. The previous afternoon, the jury had informed Judge Lance Ito that it had reached a verdict after only four hours’ deliberation, and he had instructed them to wait till morning to deliver it. The only TV in New York’s headquarters was a small set in the office of the editor-in-chief, Kurt Andersen. As the jury came back, the staff crowded in to watch. At 1 p.m. New York time, Simpson went free.

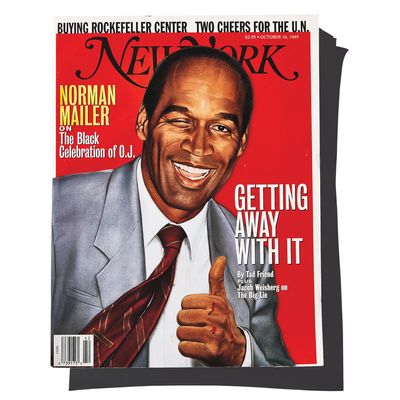

It was a Tuesday. Back then, New York went to press late on Thursday night. In the next 60 hours or so, the staff pulled together three stories and a cover designed to stand out on the newsstand. GETTING AWAY WITH IT read the headline, as a painted image of O.J. — reworked, in the interest of speed, from one that had run in the magazine two weeks earlier — winked and threw a thumbs-up at the reader. The illustrator, Tim O’Brien, put an actual smear of blood on Simpson’s hand.

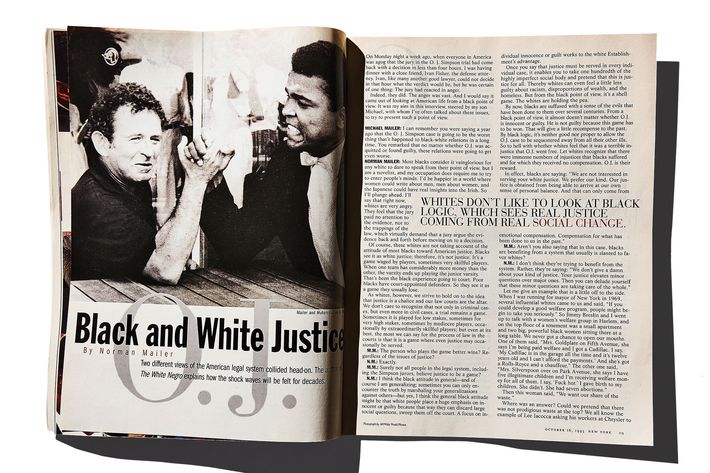

Jacob Weisberg (now editor-in-chief of the Slate Group) and Tad Friend (now at The New Yorker) quickly delivered opinion pieces. Friend wrote the title essay, about the ways in which the powerful wiggle their way free where others can’t. Weisberg’s column called the verdict “some of the worst racial news in years,” and connected black and white-liberal righteousness with conservative politicking of white resentment. But the showcase story was by Norman Mailer, author of “The White Negro: Superficial Reflections on the Hipster” and arguably the most interesting and infuriating writer of his era when it came to American violence. (He could be right, he could be ridiculous; he was rarely boring.) He was also a man, remember, who had stabbed his second wife. It was a coup to get him on a few hours’ notice, and it was, Andersen recalls today, “a case of, What we can do that goes beyond what the other guys can?” The “other guys” were Time and Newsweek, and to some extent the Village Voice and Tina Brown’s New Yorker. The New York Times Magazine had a one-and-a-half-week lead time and wouldn’t have been able to catch up. Not one of those outlets had a website yet.

Mailer agreed to do a long Q&A with his son Michael. That way, “he didn’t have to write it,” Andersen recalls, “and he could get his son a little attention.” This being the era when email was mostly for the young or the technologically inclined — and Mailer was neither — an assistant took a car service to his house in Brooklyn to pick up the results.

Which evinced a certain despair. “We’re even farther away from bridging anything. The verdict was good for black emotion but terrible for whites,” Mailer told his son. “If we can’t find some way for blacks and whites to come together, this country is going to head for fascism … if we have a major economic wipeout in America, we’re on the way toward barbed wire.” And then: “Celebrity has become our first national disease. It’s the price we pay for having neither gods nor leaders.”

The Reaction

Mailer aside, most of the attention went to the cover. “I’m glad we did it,” Andersen says. “It was slightly transgressive, it was interesting: right there on the edge. And you could still, with an oh-my-goodness cover like that, have impact that you might in the age of Twitter. That’s a social-media-fied cover. In the pre-internet day, to have a mainstream magazine come out and say ‘No, he’s guilty’ was unorthodox, and the image and the cover line were a bit extreme for the pre-Gawker age.”

Judging by the letters-to-the-editor page a few weeks later, they were. The cover was “truly revolting,” read one letter. “Outraged,” said another. “A disgrace,” read a third. One correspondent was more thoughtful, if no less critical. “So you need someone to explain black people’s feelings about the justice system. Fine. But the best you can do is Norman Mailer?” That came from Jessica Lustig — who would, a few years later, become an editor at New York, running the front-of-the-book section in which this column appears. Today she’s deputy editor of The New York Times Magazine. “We were talking here the other day about cranks who write letters,” she says, “and I had to admit that I had been one.”

*This article appears in the April 4, 2016 issue of New York Magazine.