The background radiation is still there, two decades later, from the infamous 1993 Whitney Biennial — the so-called multi-cultural, identity-politics, political, or just bad biennial. Establishment art history circa 1993 was a broken model, built on white men and Western civilization and certain ossified ideas about “greatness” and “genius.” New artists looking for new ways to speak to new audiences couldn’t get their voices heard or work seen.

There had been artists fighting this fight before, but that 1993 show was the major crack in the façade. George Holliday’s 1991 ten-minute videotape of the Rodney King beating was included as an artwork, and one of the biennial’s admission buttons, designed by artist Daniel J. Martinez, famously read I CAN’T IMAGINE EVER WANTING TO BE WHITE.

What followed was war: white-male critics gone wild. The Times’ Michael Kimmelman opined, “I hate the show,” blasting the art as “grim,” “political sloganeering and self-indulgent self-expression.” Robert Hughes said the show was “a fiesta of whining” and “preachy and political.” Newsweekdetected the “aroma of cultural reparations.” Jed Perl thought the show was calculated to get “white male critics into … [a] sweat of guilt and remorse and accommodation.” Hilton Kramer — referring to the biennial’s one African-American curator, Thelma Golden — said there was an “awful logic in having Ms. Golden on the curatorial team.” Even The Village Voiceraged that the art was angry, portentous, condescending, groaningly didactic, hateful. I was then still driving a long-distance truck and only wrote about the biennial in a now-defunct magazine. Political but no firebrand, I nevertheless suspected that the show was important precisely because of the vehemence of the art-world rejection. I quoted James Baldwin, saying that “the rage of the disesteemed” was upon us.

Amazingly, it looks like I was right about those critics. Just as amazingly, they were right about the show. Art did change! So did everything! Look around. We are living in a moment of white rage (“Make America Hate Again”), and what white America is angry about is the loss of its monopoly ownership of American culture. The story is the same in art: That biennial marked the effective end of visual culture’s being mainly white, Western, straight, and male.

And yet the transformation unleashed by the culture wars is not just about representation, diversity, numbers, and good little humanists wagging self-righteous fingers. It’s about the way culture is formed, how art is made — and what counts as art. For the first time, biography, history, the plight of the marginalized, institutional politics, context, sociologies, anthropologies, and privilege have all been recognized as “forms,” “genres,” and “materials” in art. Possibly the core materials. That shift put the artistic self front and center, making it perhaps the primary carrier of artistic content since the 1990s.

We’ve been living so long now in a culture of self-assertion that it may be hard to remember just how new this spirit is. The Impressionists were not overtly making work about “identity” or “the self”; nor were the Cubists, or the Fauvists. The entire engine of modernism, while powered by larger-than-life artistic personalities, subjugated art to work that was primarily “about” form and technique. Fast-forward to the postwar period, and the story is the same: Think of the grandiose universality of Mark Rothko’s Abstract Expressionism or Richard Serra’s and Carl Andre’s materialistic minimalisms. We think we know these artists by looking at their work, and we do; but the work is not about who they are. Even Warhol said, “If you want to know all about Andy Warhol, just look at the surface … There’s nothing behind it.”

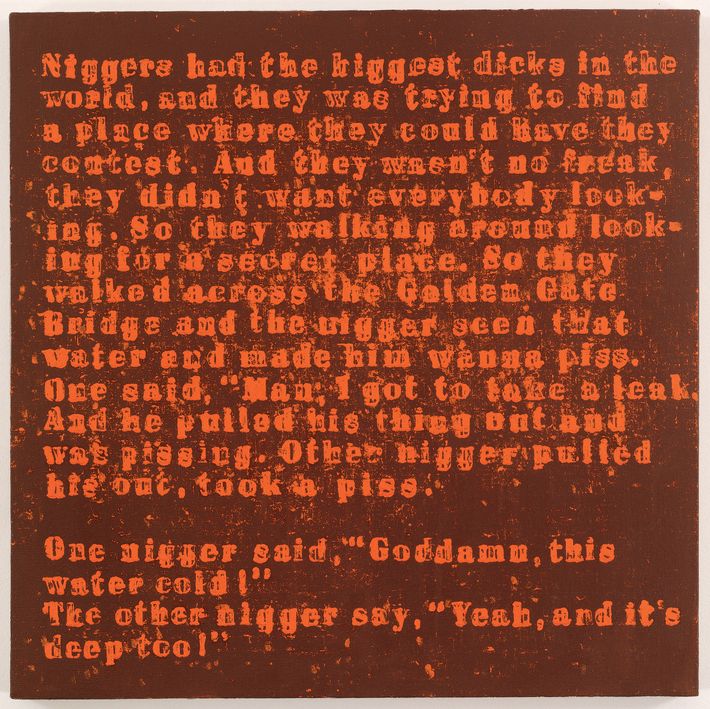

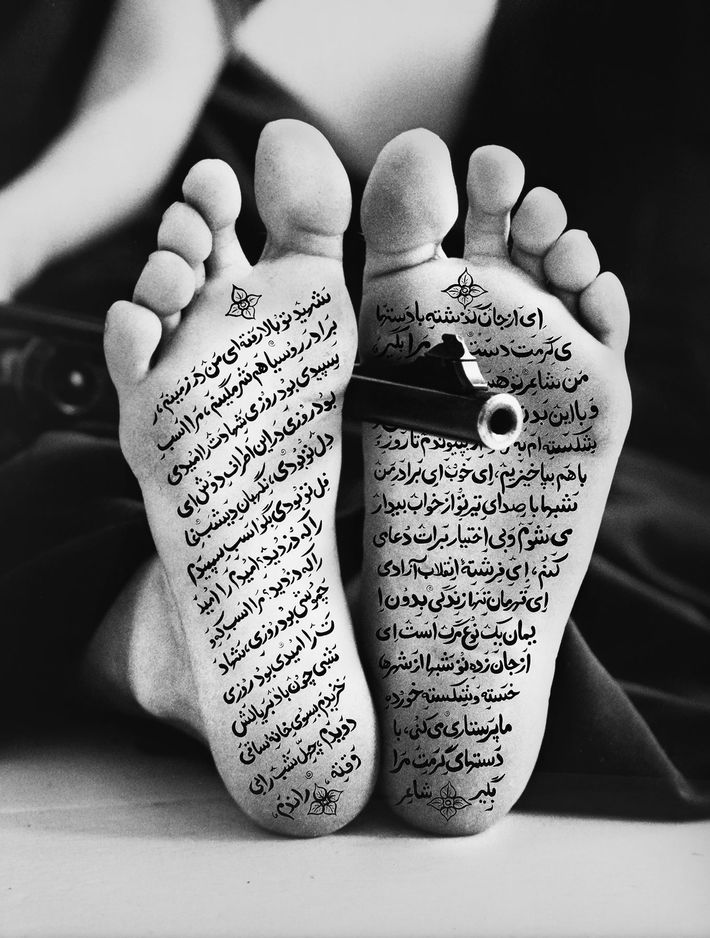

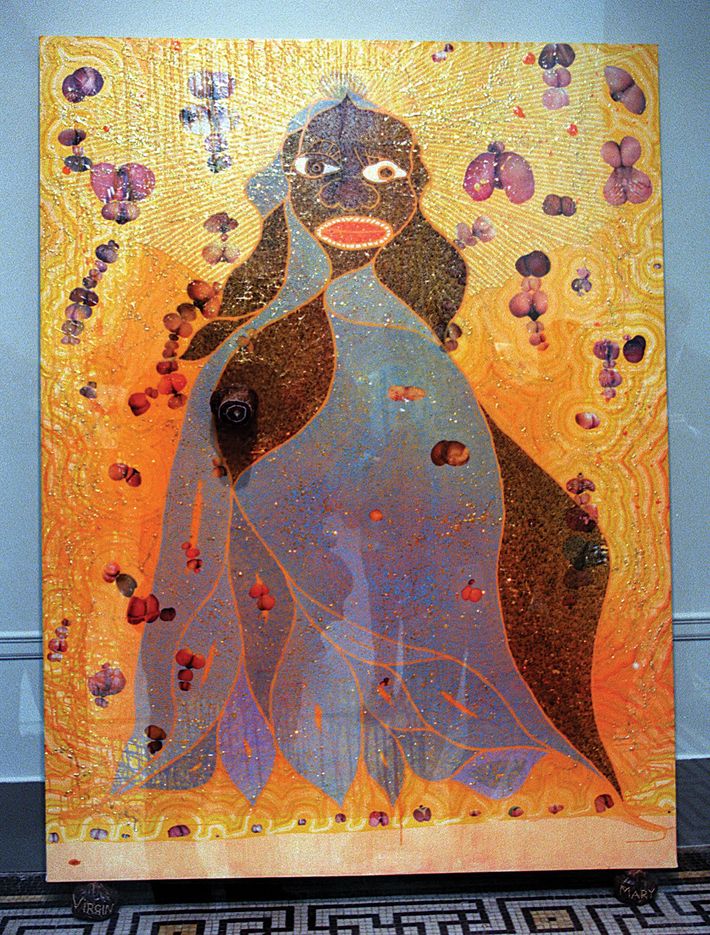

To be sure, this new transformation had roots going further back than the 1990s, especially among artists, who for decades were actively preoccupied with politics, black power, women’s liberation, gay liberation, and more. Warhol’s swishiness was revolutionary; so was Lynda Benglis posing naked with a double-headed dildo and Cindy Sherman disappearing into her film stills. But the culture-wars era, which ran roughly from 1989 to the late 1990s, brought the whole struggle to the foreground. In that period I remember seeing Kara Walker’s first cut-out panoramas of antebellum black horror at the Drawing Center and knowing that a new American Goya was unleashed; Chris Ofili’s glittery, dotted, day-glo colored paintings with elephant dung of the Virgin Mary were wildly irrational, beautiful, shamanic. Shirin Neshat created melodramatic formal films of a modern Arab world on the edge of crisis. Glenn Ligon made paintings of fraying texts from Baldwin that melted in viewers consciousness like superheated political plasma. Video artist Steve McQueen, who won the Academy Award for 12 Years a Slave, made enigmatic videos of what looked like a dead black body on a morgue table. Wael Shawky made old Italian puppets tell the story of the crusades from the Islamic point of view. Rirkrit Tiravanija served free Thai food to visitors in museums and galleries. It wasn’t just a new genre for the disenfranchised, either: white male identity was plumbed, as well, in epic operatic films of Matthew Barney dancing as a genital-less satyr. More recently, we’ve gotten the insane overload of sound, color, sensibilities, cults and tribes in Ryan Trecartin and Lizzie Fitch’s videos and the JPEG, YouTube circularity data in Hito Steyerl’s walk-in videos, films and sculptural installations.

After the ’80s, we seem to have lost the reflex to recognize or name new art movements — maybe because in the sprawling new art ecology there were so many isms sprouting at once; plus we’ve always categorized things by formal, medium-based, and geographical attributes. But something has happened here, over the last 25 years, that I am sure will be recognized with great clarity by art-history students very soon. Art in this era has veered dramatically toward an approach that hasn’t been seen in the West for more than 1,000 years: a concerted urge, almost a rage, to be totally communicative to the largest possible audiences, addressing cognoscenti, novices, and newcomers in the same register, telling stories of social, political, and philosophical conditions. Of course, not everybody today is making this kind of work. But taken together, it does constitute a real aesthetic movement, one that is biographical, autobiographical, personal — the art of the first person. — Jerry Saltz

THE BEGINNING, REALLY, IS AIDS.

1984-1991

In the Reagan ’80s, photographers like Nan Goldin and Robert Mapplethorpe document a demimonde that looks like it might go extinct. The losses from AIDS deeply affect and enrage the artistic community; identity becomes political, and so does the art. In 1987, the filmmaker and artist David Wojnarowicz captures in film and photographs the death of his lover, Peter Hujar. The New Museum stages shows like “Difference: On Representation and Sexuality” (1984), “Homo Video” (1986), and “Have You Attacked America Today?” (1989) — which led protestors to throw garbage cans through the windows over Erika Rothenberg’s DIY flag-burning kits.

The Establishment doesn’t love that stuff …

1989

Senator Jesse Helms denounces Andres Serrano’s photograph of a crucifix submerged in urine, and 107 outraged congressmen threaten to cut NEA funding in retaliation for Piss Christ and a planned Corcoran retrospective of Robert Mapplethorpe. “ ‘There’s a big difference between The Merchant of Venice and a photograph of two males of different races’ in an erotic pose ‘on a marble-top table,’ ” Helms tells the Times. The Corcoran cancels the Mapplethorpe in response, And in July, Helms introduces legislation that would prohibit the government from funding “obscene or indecent” art. Representative Dick Armey of Texas said that if the NEA did not adhere to new moral guidelines he would show his colleagues the Mapplethorpe images and “blow their budgets out of the water.” Thus begin the culture wars.

… But the art world won’t back down.

1989–1990

Protesters respond to the Corcoran decision by projecting Mapplethorpe’s photographs onto the museum’s façade. And other marginalized artists join in.

The “masked feminist avengers” known as the Guerrilla Girls — still active, still anonymous — conducted a “weenie count,” finding that less than 5% of the artists in the Met are women (but that 85% of the nudes are female). The Guerrila Girls plaster their posters around town, and later visit the CalArts class of photographer Catherine Opie: “They said, ‘Girls sit on this side, boys sit on this side,’ and then they threw bananas at the boys. I thought they were brilliant.”

Inspired by protest-art groups like ACT UP spinoff Gran Fury — which produces “campaigns” like “Kissing Doesn’t Kill: Greed and Indifference Do,” “Art is Not Enough” and, most famously, “Silence=Death,” a neon sign which hangs in the window of the New Museum — the activist group Visual AIDS persuades hundreds of art organizations to institute a “day without art,” and shroud work in “mourning and action in response to the AIDS crisis.” Many of them display informational posters and brochures over the shrouded works.

And Godzilla, the Asian American Art Network, lambasted the new Whitney director for the lack of Asian-American representation in the museum’s last biennial. “Of course, we were fully aware that David Ross had not been involved with that biennial,” says Eugenie Tsai, now a curator at the Brooklyn Museum. But “after, receiving the letter, David, to his credit, invited a contingent from Godzilla to speak to him at the museum.”

(Nor will right-wing standard-bearers.)

1990

A grand jury indicts the Cincinnati Contemporary Arts Center and its director, Dennis Barrie, on charges that images in its Mapplethorpe survey are obscene.

Ultimately a jury finds Barrie not guilty, but he finds it “very hard to get back to life as normal after that,” he says. “And the CAC wanted to leave it behind. It had impacted funding and alienated certain audiences, so they were saying, ‘Let’s get on with it and never talk about Mapplethorpe again.’”

In February, California congressman Dana R. Rohrabacher asks whether the prostitute-turned-performer Annie Sprinkle’s show at The Kitchen — “Post Porn Modernist,” during which she recounted tales of sleeping with 3,000 men — sounded “like an appropriate use of tax dollars to you?” Sprinkle defended herself: “My money goes to a lot of things I don’t like. I’m paying for nuclear bombs. I’m paying for wars… My tax dollars are going for art that I think is really stupid and boring and trivial.”

Later, the NEA begins requiring that its grantees declare in writing that their work would not be obscene and vetoes grants for four artists, including Karen Finley, who was known for smearing herself with chocolate and for inserting yams into her body. (“It was all about the body and shoving yams up one’s ass, and I was like, ‘whoa she’s really going for it,’” says Catherine Opie.) When Finley leads a First Amendment suit against the NEA, she becomes a kind of martyr to the cause.

The New Art is immediate, political.

1990

The New Museum presents “The Decade Show: Frameworks of Identity in the 1980s.” It is “a turning point for sure,” says Lisa Phillips, now director of the New Museum. “It took up homosexuality, gay sensibility, gender issues, and issues of race and identity. These were firsts in the museum world. I remember very clearly an art historian saying to me that the next decade is going to be all about artists of color.”

“It was exciting,” says Steven P. Henry, who was working in public programming at the New Museum then. “It felt like you were part of something that was really important to the discourse of culture.”

Carrie Mae Weems puts the black female experience in front of the camera.

1990

In a series of self-portraits, Weems plays solitaire, puts on lipstick, and sits with her family. “I was really excited to see a theme that felt familiar to me in the context of great art and the historical canon,” says the artist Rashid Johnson. “I know that scene — you know, I sat with my mother at that kitchen table. Less familiar was Henri Cartier-Bresson. Very familiar was Carrie Mae Weems.”

Glenn Ligon makes idiosyncratic annotations of older artwork.

1991

Ligon starts to annotate Mapplethorpe’s 1986 photography book of nude black men, The Black Book. He eventually hangs each page separately on a wall, accompanied by a notecard annotating it with quotes from writers like bell hooks and James Baldwin. He titles it “Notes on the Margin of the Black Book.”

A later work features crate sculptures embedded with recordings inspired by the story of escaped slave Henry “Box” Brown, who mailed himself to Philadelphia in a crate, and, when he emerged, began to sing. “I vividly remember coming up the stairs from an art history lecture and seeing that installation — and then returning again and again,” says Darby English, now a consulting curator at MoMA. “That was the period of my first really intense curiosity about what it would mean to be an ‘art intellectual.’”

Felix Gonzalez-Torres and Rirkrit Tiravanija make art so intimate you can eat it.

1991

Gonzalez-Torres creates a “portrait” of his partner, who has died of AIDS, in the form of a mound of candy that gallery visitors are invited to take from. The next year Tiravanija (a Thai-Argentine) serves Thai curry to gallery and museumgoers. (“The smell of the cooking was part of the piece,” remembers gallerist Jack Tilton.) Later, he re-creates a perfect model of his East Village apartment in Gavin Brown’s gallery, where visitors hang out and party; some even have sex.

David Hammons becomes the movement’s godfather.

1991

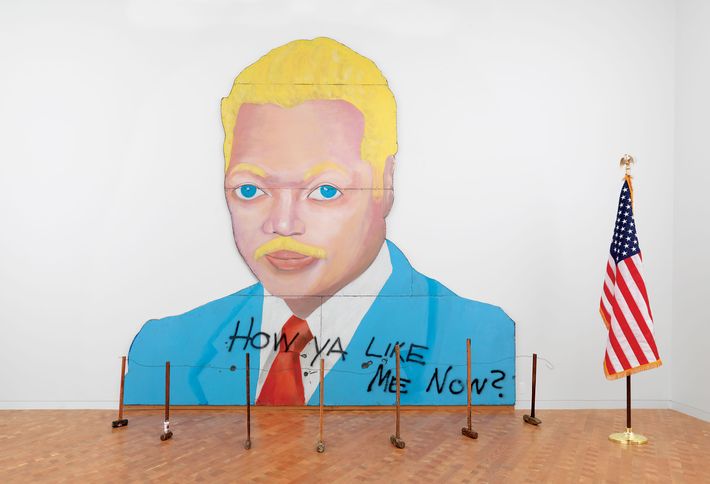

The legendary outsider wins a MacArthur “genius” grant, having produced politically charged art since the ’70s, like his paintings of a white Jesse Jackson and a three-story basketball hoop. In possibly his most talked-about work, Hammons, who once said “I can’t stand art, actually,” sets up next to street vendors to sell snowballs priced according to size. “In a way what happened in say the late ‘80s or beginning of the ‘90s was that finally the art world’s scales fell from their eyes and they realized that, wait a second, all this is real and we don’t know anything about it,” says the sculptor John Ahearn. “I think it started with David Hammons.”

Artists make work explicitly about exclusion …

1991

Fred Wilson completes Guarded View, an installation of headless museum security guards wearing uniforms from New York City’s art museums. “I didn’t know I could be an artist before I saw that work,” says Rashid Johnson. “I didn’t know that people like me were making that art about themselves and the complicated experiences they had. I was maybe 19 or 20 then. Before that, to me, art was Gauguin. Or maybe Pollock. It really changed my life.”

Brooklyn Museum curator Eugenie Tsai cites the work today to show how little has changed: in nonprofit cultural institutions, 79% of curators are white and 21% are people of color, while 31% of security staff is white, versus 69% people of color.

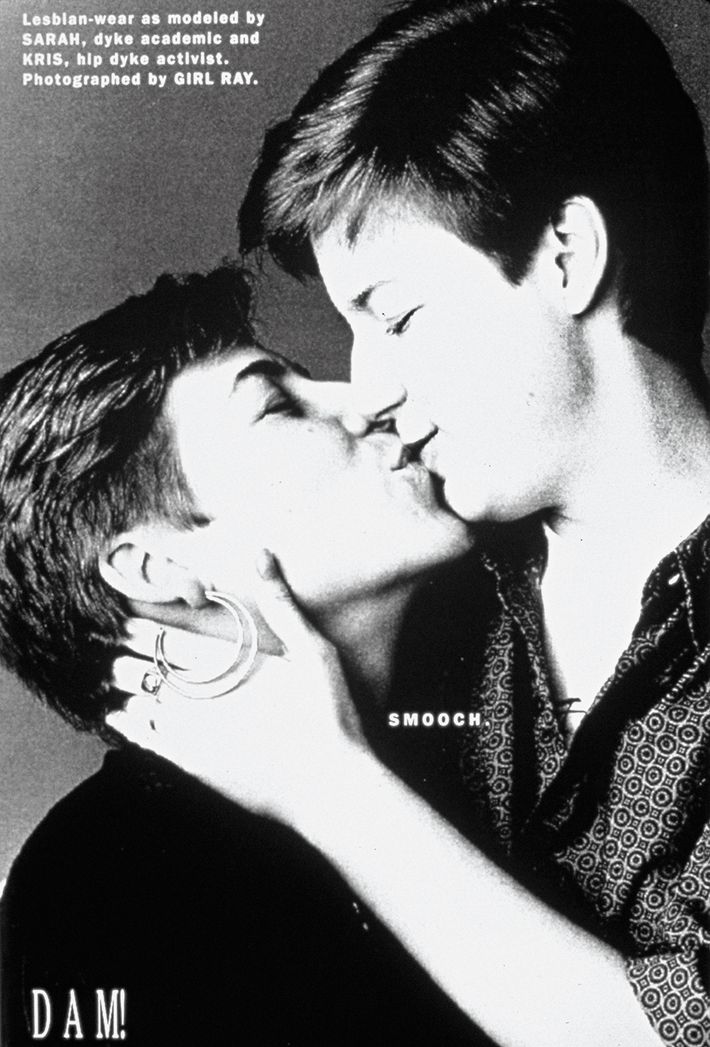

… And place that art right where the public can see it.

1991

Carrie Moyer and Sue Schaffner form Dyke Action Machine, a fauxadvertising duo; their debut campaign mimics Gap ads, but with photos of women kissing. “There was a lot of excitement about our projects in the queer community and we developed quite a following,” says Moyer. “They critiqued the world — with great graphic style and cutting humor — from the dyke-on-the-street’s point of view.”

THE WHITNEY BIENNIAL BREAKS THE LEVEE.

1993

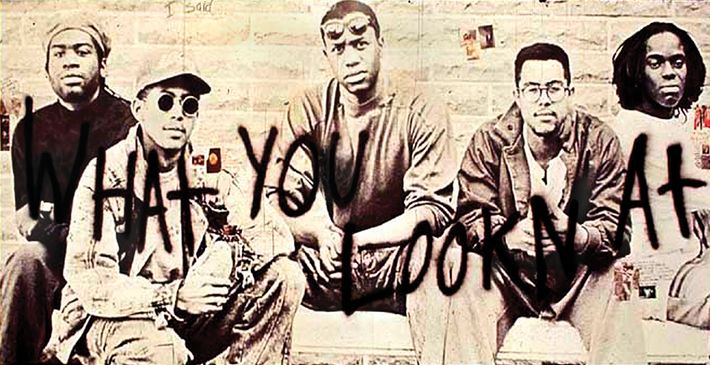

Overseen by Elisabeth Sussman, the biennial has a singular vision. “Artists insist: know thyself,” the then-director David A. Ross writes in the show catalogue. “By any means necessary!” Insist they did: Robert Gober’s handmade newspapers with headlines about the gay “threat” to marriage; the graffitilike scrawl on Pat Ward Williams’s mural of five young black men asking viewers “What You Lookn At”; and Pepón Osorio’s installation of a cramped Latino home featuring a corpse covered with a bloody sheet — The Scene of the Crime (Whose Crime?). Elsewhere in the show, a video replays the Los Angeles police beating of Rodney King in its entirety, without comment.

David Hammons declines to participate. “We all hoped he would, but he didn’t want to,” recalls Ross. “But on the night of the opening, there he was, standing silent and alone under the streetlight on the northwest corner of Madison and 75th Street. He seemed to be simply watching people coming into and leaving the opening. I’m not sure what he meant this nonaction to communicate, if anything. But I read it as a message that this exhibition, despite our attempt to reflect an understanding of that particular moment, should not be confused with a solution to the problem.”

Critics can’t stand it.

1993

The show becomes one of the most widely criticized exhibitions in the museum’s history. Michael Kimmelman writes in the first paragraph of his New York Times review: “It has brought various New York critics of usually discordant opinions into rare harmony: at the least, they dislike it. I hate the show.” Robert Hughes’s Time review was subtitled “A Fiesta of Whining.” Peter Schjeldahl of The Village Voice says the show “really may have been the worst ever.” “The show was rough and vulgar,” says Schjeldahl now. “I reacted against that. I resisted the truth that it embodied a necessary force of history, squaring the little art world with big values of democracy. But truth will tell, and I came around. Art survived just fine. The event was good for society and, gradually, by the way, for me.” Michael Kimmelman is less contrite: “My 93 piece in retrospect seems to me heartfelt and clear,” he says. “It’s not against the idea of a more politically engaged biennial or art world, but against the specifics of that show. Politics matter.”

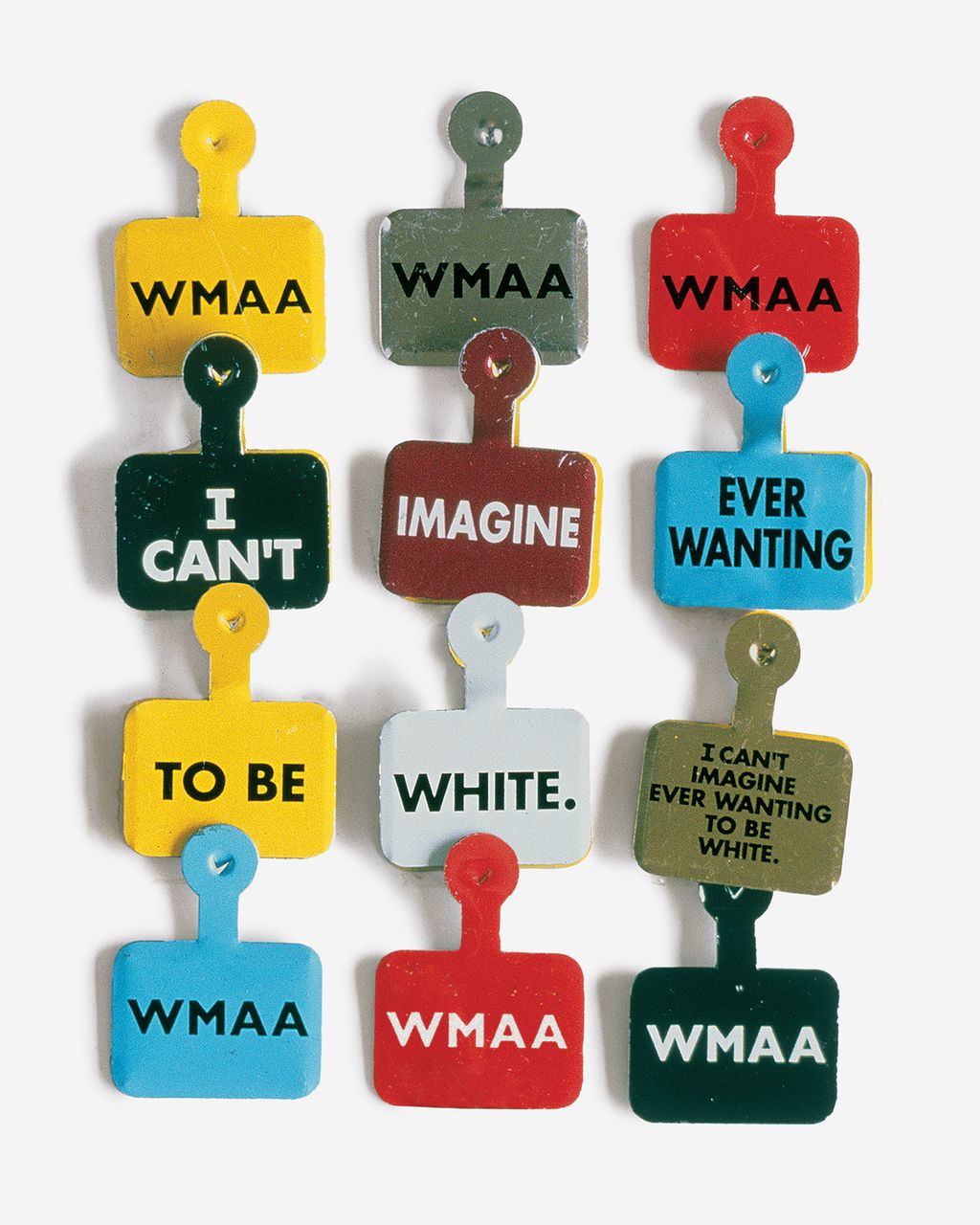

Especially Hated Are the Daniel J.Martinez–Designed Buttons.

1993

Martinez, an L.A. multimedia artist, has already been making provocative, politically charged art before being tapped to make the entry buttons for the show. “Before the tags I had all kinds of museums and galleries wanting me to do shows,” he says. “Then the biennial happened and I couldn’t buy a show. No one would touch me. The tags themselves are completely misunderstood. Arthur Danto was beside himself with anger. Like most white people, he didn’t know what to do with it. People started every article saying, ‘Daniel Martinez is a reverse racist’ and I was like, ‘That’s the best you got?!’ I relish anyone with an intellect who is really willing to do the work, but instead what you got was a bunch of responses from people I wouldn’t even ask to pick the colored towels in my bathroom.

My piece in particular completely changed the identity of the Whitney Museum. They were never able to go back the same way because it had altered its institutional profile. We believed the battle had been won. We thought that if you could have the Whitney commit its resources to [this conversation] then it only seemed logical that everyone would follow suit. We didn’t think the reaction would be, ‘this is the worst thing that ever happened.’ It should’ve been a cue to anyone that art could be richer, more fantastic, and why would anybody want less? Instead the response was the most neo-con reaction possible. There were 800 or 900 reviews written and they were basically like, ‘Who let the queers and minorities into the museum?’ instead of embracing a reality of inevitability in this country. We were wrong. We were wrong.”

Even the show’s curator is stunned by the response.

1993

“By the end of the 1980s, anyone who was working as a curator knew they had to bust out of the white ghetto,” says Sussman. “But these were arguments contained at the margins, not the center of the art world, and I’d consider the Whitney the center.” Inspired by downtown spaces like Kenkeleba House, the New Museum, and Exit Art, Sussman works directly with collectors, curators, and artists, rather than galleries, to find new voices that hadn’t yet been screened by the market. “It was absolutely important to take on what I, as the lead curator, thought was the most important thing happening at that moment in America,” she says. “Biennials are always controversial; you know that going into it. But I certainly did not expect it to this extent. The reviews were very aggressive. It was Kimmelman who really got the argument up to the high decibel, and he was a new critic at that time. It was like a field day for critics. I didn’t go to the board meetings, but I felt as staff that I had to be protected in some way. These were not easy times.” But the show changes things, for sure. “I think it’s taken for granted now that biennials will take a political position. It’s almost a cliché now. They’re now seen as a platform for diversity and progressive thinking — if they don’t do that then it seems like they haven’t done their job. That wasn’t the case before 1993.”

IDENTITY FLOODS INTO THE ART WORLD

1993–1999

Led by Thelma Golden, the 1993 biennial’s one black curator. Golden is not yet 30 when she curates “Black Male” at the Whitney, which features work by Fred Wilson, Adrian Piper, Leon Golub, and Barkley L. Hendricks. “One striking thing was a certain antipathy toward the exhibition, if not necessarily toward Thelma, by an older generation of African-American artists who believed their work had been ignored by museums in the city,” remembers Okwui Enwezor, then a young transplant from Nigeria (and later a Venice Biennale curator). “What was revealing to me as a young curator was the schism that suddenly seemed to exist between my generation, of which Thelma was a definite leading light, and the generation of cosmopolitan, sophisticated, and accomplished artists who had never been properly foregrounded within American art history. ‘Black Male,’ as the title so astutely and polemically underscored, was not only a psychic battlefield but also an epistemological battlefield. It was such an unforgettable, generation-defining exhibition. Step into any American museum today, and you will see the imprint of the show everywhere. It was absorbing, disturbing, salient, and analytically incisive.”

“Golden is a story unto herself,” says Coco Fusco. “How influential she has been in helping my generation of black artists to break in into major museums and collections in a very significant way. Prior to the late 80s or early 90s there was very little hope that could happen. The people who kept artists alive — they are few and far between.”

Artists pick up the gauntlet.

1994

Shirin Neshat launches her “Women of Allah” photography series. Anna Deavere Smith’s Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992, a one-woman show dramatizing the Rodney King beating, is nominated for a Tony. “Instead of using a kind of documentary form, instead of writing a play or making an artwork, she actually used her own body,” says Harvard professor Homi Bhabha.

Then, the world is introduced to Kara Walker.

1994

“Kara was in her last year at RISD when she sent her slides to us, and they totally knocked us out,” says Ann Philbin, then the director of the Drawing Center. Walker has just begun working with cut-paper silhouettes, using them to depict not idyllic Victorian scenes but antebellum horrors. “Honestly, it didn’t happen that often that we would be that surprised and impressed. The work was like nothing we had ever seen before. We called and asked her if she could transfer the silhouetted cutouts that she was putting on paper and scale them up to a wall surface. I recall that weeks went by before she called us back and said she could do it. The work she presented in our exhibition was extraordinary, shocking, and intensely confrontational on the issue of race. Its ambiguity was very provocative, and a lot of controversy swirled around Kara. She was a black woman, but who did she speak for? And was the work’s message politically clear enough?”

Later, artist Betye Saar would criticize Walker on PBS: “I felt the work of Kara Walker was sort of revolting and negative and a form of betrayal to the slaves, particularly women and children; that it was basically for the amusement and the investment of the white art Establishment.”

And the shock-and-awe biennial model gets exported.

1995

All the way in Korea, the Gwangju Biennale is founded in response to the Whitney Biennial. “Nam June Paik was our kind of unofficial sponsor,” says curator Elisabeth Sussman. “They loved it there. They were in total awe. I don’t think they picked up any of the outrage about political art. They thought it was hot and controversial and, as a result, they started their own biennial which is now world-famous.”

And artists of color finally find galleries to call home.

1990s

“It’s not just about selling but finding rep-resentation,” says the curator Robert Storr. On that front, Jack Shainman “had done more than anybody.” In 1997, Shainman’s gallery moves to Chelsea. “There was a shift once artists of color started being represented and showing in galleries; they actually had a presence in the marketplace,” says Steven P. Henry, the director of Paula Cooper Gallery. “You still had Romare Bearden and Jacob Lawrence, but they were always framed as black artists, whereas Jean-Michel Basquiat was a superstar, and I think his success did redefine how an artist of color could be collected.”

Coco Fusco sees the boom a little differently. “Collectors, it doesn’t take very much. There aren’t very many in the US that buy contemporary art to begin with and all it takes is a few and then it takes off. If one person turns out to be a good sell then other gallerists follow suit. They say, ‘I’m gonna get my black person,’ and that’s essentially what happened.”

“Bank balance is the most effective measure of alienation or inclusion,” says artist Kenya (Robinson). And not everyone makes money, even in a boom. “Kara Walker has an amazing market, Glenn Ligon,” says the critic Antwaun Sargent. “But it’s just too few.”

This is no paradise of inclusion — particularly for women and Latino artists.

1990s

“Unfortunately, I think the art world today is possibly more sexist,” says Lisa Spellman, pioneering gallerist of 303 Gallery. “Whatever gains have been made are hard-won, inconsistent, and precarious,” says Douglas Crimp, a professor of art history at the University of Rochester.

“Many marginalized artists were briefly included in the mainstream art world only to have their art dismissed as examples of ‘identity politics,’ ” says Bridget R. Cooks, author of Exhibiting Blackness. “The term was used to degrade work that critics did not want to spend time understanding because it dealt with histories that they believed did not belong.” “The way white America perceives its fulfillment of diversity is caught in this binary of black and white,” says Jorge Daniel Veneciano, executive director of El Museo del Barrio. “Look at how many shows by a Latino most major museums have done, and it’s often none or only a couple in their entire history,” says artist Teresita Fernández.

“I always felt alienated because I used to say no to being included in Latino-art surveys,” says artist and writer Pedro Vélez. “I think institutional folks took it as an insult. Maybe they felt I was being ungrateful. What did the 1993 Whitney Biennial achieve, when we had, like, four white Artforum writers trying to explain racial inequality in Miami Basel during the Black Lives Matter protests?”

But art institutions are taking note.

1994–1999

In 1994, the Bronx Museum stages the landmark immigrant-art show “Beyond the Borders,” which Shirin Neshat says “established my career”; in 1995, the UC Berkeley Art Museum does the same for queer art with “In a Different Light.” In 1996, the New Museum launches a retrospective of Carolee Schneemann, most famous for reading from a scroll she extracts from her vagina. Kara Walker wins a MacArthur “genius” grant. And in 1999, “The American Century” opens at the Whitney. “What makes someone an American artist was suddenly impossible to state without a lot of discussion,” says the critic Thyrza Nichols Goodeve, who worked as a consultant on the show. “While ‘American’ made sense as an organizing principle of the first half of the show, the whole point of the late 20th century was that ‘American’ had became a contested term because of the rise of globalization, identity politics in the art world and international biennials.”

Museums even invite artist Fred Wilson to reassemble their collections to openly display their prejudices. (That work, beginning with his landmark “Mining the Museum,” “showed me that the stakes of institutional critique could be higher, or perhaps deeper, than navel-gazing aestheticism,” says Mark Tribe, an artist and founder of Rhizome.) “It’s the first time that you see a real embrace, institutionally and commercially, for the work of artists who’ve had a difficult time being embraced prior,” says Rashid Johnson. “I had assumed this was to be an uphill battle and the mainstream would prevail,” says Lowery Stokes Sims, who was the Met’s first African-American curator. “Thirty-five years later, it was evident that the work and struggles of me and my colleagues had had some effect.”

As are art critics.

1998

Holland Cotter, who began publishing in the New York Times in 1992, is hired full-time in 1998 — and (himself a white man, though gay) writes almost exclusively about queer artists, artists of color, and the previously excluded. “It seems like a waste to do the 1,000th Richard Serra show or whatever,” he says.

And when Rudy Giuliani launches his crusade against this painting, it marks the end of the culture war …

1999

Some suspect that the outrage against Ofili’s The Holy Virgin Mary, which prompts the New York mayor to threaten to evict the Brooklyn Museum, is driven less by the elephant dung used to adorn the Virgin than by the color of her skin. In cosmopolitan New York, Giuliani’s crusade is a PR disaster.

… With art values victorious.

1999

(It’s the year Karen Finley appears in Playboy, after all.)

THE THEATER OF THE SELF IS BORN

2001-2016

Golden asks: Can black art move past multiculturalism?

2001

At her new post at the Studio Museum in Harlem, Golden curates “Freestyle,” which coins the term “post-black” to describe artists who might seem liberated from identity politics by the market boom in black art. “The whole hullabaloo around the Freestyle exhibition, and around the term post-black, which makes some people very angry, is the subtext that black artists don’t have to complain anymore; now they can make art about whatever they want,” says artist and writer Coco Fusco. “They don’t have to talk about slavery, racism, the abject. The political edge of black art doesn’t have to be there anymore for the work to be authentic. But what is that really about? A certain part of it is complacency that comes from economic well-being. If you’re selling to collectors why are you going to be upset? That’s one of the effects of the market. There’s a new set of goals and a different set of goals today: one about instant fame, success and money, not about a less-commercially driven pursuit of ideals. When I go to see shows now with very young black artists it’s very clear what their goals are: they’re commercial, very commercial.”

“I thought it was a really good show,” says Rashid Johnson, one of the younger artists included. “It’s hard for me to look at those exhibitions and think ‘this is a bad idea’. Mark Bradford comes from that exhibition initially. I do, so does Julie Mehretu, Eric Wesley. But I don’t know what the fuck post-black is. I currently am and have been black from the time I can remember so I’ve never been post-black. It was probably quite necessary for [a previous generation of black artists] to essentially teach white people about the black cultural experience. But I grew up in the BET generation, so white people knew a lot about black culture. I didn’t need to tell them about my hair. They knew what dreadlocks were. They understood the vernacular. These issues have been so importantly addressed by artists before me that I never felt I really had to address them.”

And other doors crack open …

2002

Betty Tompkins exhibits her “Fuck Paintings” — which she began in the ’70s but could never show before. “I was totally rejected in the ’80s and ’90s and totally rejected by the feminists,” Tompkins says. “I was making work that involved pleasure, and there was one segment of feminists who were against making work about female pleasure.”

… Giving way to a whole new genre — performing who you are.

2003

Kalup Linzy creates his mock soap opera, All My Churen, which he often plays in drag. “It was inspired by comedians like Eddie Murphy and Martin Lawrence and growing up watching soap operas,” he says. “I wanted to create characters that explored the definition of stereotypes and archetypes, and not have them be one-dimensional. I was also exploring my personal identity in relationship to family.”

In 2005, Performa launches the first performance biennial, with identity-focused artists including Marina Abramovic, Ron Athey, Sharon Hayes, and Clifford Owens, whose later show at PS1, “Anthology,” restages the whole history of performance art from the perspective of excluded black artists by performing particular “scripts” — one of which, written by Pope.L, is “Be African-American. Be very African-American.”

Performance art has histor-ically been a vessel for exploring identity, says Performa founding director RoseLee Goldberg. “What better way to make people pay attention very directly than to say ‘Look at me, I’m standing right in front of you.’ ”

Even art by white men starts to look different.

2000s

“Matthew Barney’s a trans artist, but not in the contemporary sexual sense,” says Homi Bhabha. “He’s doing it by translating the experience of boundaries across materials and practices while acknowledging the peculiarity of each medium. He takes questions of gender and sexuality into his own body and complicates them.” And newer work by white men shows the performative-identiy influence: The video installations of Ryan Trecartin tackle sex, culture, and race; men become women become clowns become micropersonae become mirrors.

The Establishment really begins buying in.

2000s

In 2007, Lorna Simpson, who often combines images of black women with her own text commentary, gets a retrospective at the Whitney. “Walking through the show, I cried,” says gallerist Jeanne Greenberg Rohatyn, who shortly thereafter begins representing the artist at her gallery.

The same year, Kara Walker gets her own Whitney retrospective at just 37. “As I went through the show, I began to own a history in a way I never had before,” says Laura Hoptman, curator of painting and sculpture at MoMA. “I realized that the history that Kara was mining was my history as much as hers.” Later in 2014, Walker takes over Brooklyn with A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby, a monumental “mammy”-sphinx at the Domino Sugar Factory in Brooklyn. “I saw the Kara Walker, and all I could think about was a great Biggie line, ‘Sweetness, where you parked at?,’ ” says Jay Z. “Genius at work.”

This often still means support from white patrons.

2008

“’You’re out of your mind to be white collectors doing a show by black artists,’” recalls Mera Rubell about “30 Americans,” the 2008 Rubell Family Collection show featuring work by David Hammons, Kehinde Wiley, Renée Green and other black artists. People were saying, ‘you’re walking into a beehive here. You’re going to be accused and embarrassed’ and, honestly, there was a moment where we wondered as a family, are we willing to take the risk? Artists would say, ‘I don’t want to be ghettoized, I’d rather hang with Richard Rrince than be in a show with “black artists” because what do I have in common with black artists as such? But we met with Rashid Johnson at a round table at Balthazar and we said you’re one of the younger artists we’re curating into the show and we want to know how you feel about it. Do you feel it makes sense to do a black show? And he says ‘why not? You own the work.’ I don’t know if he even knew Glenn Ligon or Mickalene Thomas was in the show then, but he said it would be such an honor to be in the same show as Hammons. At some point we ran into Kerry James Marshall on the street in Chelsea. We were on our way to Jack Shainman and I said, ‘Can we borrow Jack’s office for a few minutes to have an intense conversation with you?’” she says. “We walked out of there like we were walking on the moon because we finally had the blessing from who we really thought was the priest.”

“There’s an affinity people have for aesthetics belonging to a culture other than their own,” says Taylor Renee, co-founder of Arts.Black. “I’m reminded of a recent Ebony Magazine cover that stated; America Loves Black People Culture, with a strikethrough the word ‘people.’ This is nothing new, America has appropriated Black culture for centuries, but I think in a time where black bodies are becoming more and more visibly disposable, there is this innate form of resistance by black Americans that is warranted. We are experiencing a tipping point where black Americans are holding historically all white institutions accountable for their injustices against marginalized groups.”

Though some icons of diversity resist being labeled.

2000s

“The identity politics of the ’90s were quite formative for me,” says artist K8 Hardy. But today, “I feel that my work is minimized by simple references to identity politics, so I’m hesitant to discuss!” “Being transgender, I never saw myself represented anywhere,” says artist Leidy Churchman. “But I am a selfish artgoer. And I’m really looking for little bits of excitement and content for my own work.”

And wonder just what can be achieved.

“Artists respond to their culture and the world they’re living in,” says the artist Martine Syms. “By 1993 HIV became the leading cause of death for black men 25-44, and the second cause of death for black women. We lost a generation of Americans during the AIDS crisis due to a prolonged, dehumanizing campaign that targeted queer, poor, people of color. Not to mention, millions were being imprisoned under the auspices of a war on drugs at the same damn time. I think ACT UP was incredibly successful, but I feel like focusing on that is missing the point of art. Did their work end structural racism, um, no I guess not… “

With social media, artists can now speak even more directly …

2010-2015

Artist Jayson Musson debuts his “Art Thoughtz” YouTube series, starring his alter ego, Hennessy Youngman. In “How to Be a Successful Black Artist,” he advises, “Appear to be angry, be unpredictable and exotic to white folks. Appear to be in line with black intellectual fads and what have you. Exploit slavery in the production of art objects in order to satisfy the voyeuristic needs of bourgeoisie white consuming audiences and say you’re doing it to ‘challenge’ them so basically when they leave your provocative and challenging solo exhibition they have something to talk about while they eat dinner at the Russian Tea Room. Follow that and you’re gonna be a very successful nigga artist.”

In 2014, the artist Shikeith creates the hashtag and video project #Blackmendream. “It’s a way for black men to talk about their fears and anxieties; it’s also about black male sexuality, the way we perform it, live it, and dream about it. It’s a work that’s really getting out there,” says the critic Antwaun Sargent.

The next year, artist and “conceptual entrepreneur” Martine Syms dissects the mannerisms of black women in her performance video Notes on Gesture. “She works in ways that black artists are more drawn to these days: videos and online platforms,” says Sargent. “Notes on Gesture has to do with black female gestures that have traveled across the internet. She has an actress doing performances of those gestures and it’s really ridiculous, but the point being a meditation on black femininity and languages that are not easily captured, but that definitely exist among black women.”

… And sell and market work themselves.

2011–2014

Kimberly Drew of the Met starts the Instagram @MuseumMammyand founds the Tumblr Black Contemporary Art. “I think what’s going on now is a bit different,” she says. “I’m a total digital kid. I’ve had a computer since I was 6. I wanted constant contact and couldn’t find it. So I just decided to start my own site.”

In 2014, Jessica Lynne and Taylor Renee start the online journal Arts.Black. “As much as there is an under-representation of black people within art museums and cultural institutions, there is also a void of black writers being published within the field of art criticism,” says Renee.

“Today artists are saying, ‘I want to sell my work the way I want to sell it, talk about it the way I want to talk about it,’ says Antwaun Sargent. “Even if there is a market, the other structures that make up the ‘art world’ are still also very white and I think people are a little frustrated with that.”

IRL artists carry the activist torch

2000s

In 2010, Theaster Gates’ Rebuild Foundation begins revitalizing underserved communities in Chicago through arts and culture initiatives. In 2011, Carrie Mae Weems helps launch Operation Activate, a public-art project against gun violence. In 2015, Mark Bradford, collector Eileen Harris Norton, and activist Allan DiCastro open Art + Practice to provide cultural programming in low-income Los Angeles neighborhoods.

And the signs of revolution are everywhere.

2000s

The 2010 Whitney Biennial features a majority of women artists for the first time. Glenn Ligon’s “America” retrospective opens at the Whitney. Megagallery Hauser Wirth & Schimmel inaugurates its mammoth L.A. space showcasing 50 years of female sculptors, and Jack Shainman opens two new gallery spaces. The first show composed entirely of black artists goes on view at Yale, M.F.A. student Awol Erizku’s “13 Artists.” (“It was not an initiative of the faculty; the students did it because they weren’t getting what they wanted,” says Rob Storr, then the dean of Yale’s art school. “Faculties are not diverse. They’re not entirely monochrome, but they’re overwhelmingly monochrome.”) The ambassador to South Africa is trying to bring “30 Americans” to Johannesburg, says Mera Rubell. The Brooklyn Museum mounts a Kehinde Wiley retrospective. (“It was my awakening moment,” says Kimberly Drew. “I felt something happening in me — there was a considerable shift. I’d been coming to museums throughout my life and I had never seen anything like that before. Just being in that room and seeing people that looked like me was incredibly profound and moving.”) Frank Benson’s sculpture of Juliana Huxtable’s nude, transgender body becomes one of the most-talked-about works in the New Museum Triennial. The Whitney calls the major exhibition, drawn from its own collection, with which it opened its new building, “America is Hard to See.”

As are the arguments.

Today

When in 2014 white artist Joe Scanlan introduces a character played by a black woman into the Whitney Biennial, the mostly queer and black Yams Collective withdraws from the show. “We are protesting institutional white supremacy and how it plays out,” a Yams member told Artnet News. “A main part of our message is that we want to move the idea of white supremacy away from caricatures of white supremacy: neo-Nazis, KKK members, crazy kids who live in the mountains of Arkansas. White supremacy is embodied in these institutions that tokenize us, that invite us into spaces where they have absolutely no interest in ceding power. That’s the most important thing to get about this.”

Unsurprisingly, Scanlan sees himself working in pursuit of the same values. “Donelle Woolford springs from the fact that, while museums have made great strides in expanding the points of view in their programming, there is still an expectation that in order for artists of color to gain access they have to make work about their identities,” he says. “That is, requires them to demonstrate they’re authentic. This was and remains a kind of trap that disciplines all artists who don’t make work about their identities and constrains those artists who do. Even when an artist of color plays with this authenticity and control — say Adrian Piper or Pope.L — their actual identities are still used as proof of a momentary, but authentic achievement of diversity. We wanted to see what would happen if a character like Donelle Woolford entered this system, what would happen when her identity was revealed to be performed, inauthentic. Needless to say, her presence has been transformative. The protest and withdrawal by the Yams Collective wouldn’t have been effective without the catalysis of Donelle Woolford. The same is true for all museums and curators who now feel compelled to take their commitments to access seriously. As Marcel Broodthaers said, ‘Fiction enables us to grasp reality and, at the same time, that which is veiled by reality.’”

“We are at an interesting moment in America today,” says Okwui Enwezor. “One that I believe is quite analogous to what has been termed the ‘heyday’ of identity politics in the late 1980s and 1990s. This in my view is very welcome, particularly in the way different forms of engaged art and activism bring a spotlight to the types of clueless and insipid formalism that was running amok in galleries and museums recently in the name of a revitalized painting.”

Which makes first-person art, undeniably, an art-historical movement – the movement of our time.

Today

Jerry Saltz: “Artists now work at the scale of medieval cathedral façades, meant to tell universal stories in highly accessible ways. But they do so with their own personalities, histories, biographies always front and center — speaking, imploring, knocking us down with the idea of a self.”

—History by Rachel Corbett

This project was assembled from interviews with John Ahearn, Dennis Barrie, Frank Benson, Homi Bhabha, Claire Bishop, Francesco Bonami, AA Bronson, Susan Cahan, Dan Cameron, Rodriguez Calero, Leidy Churchman, Bridget R. Cooks, Lauren Cornell, Holland Cotter, Douglas Crimp, Vaginal Davis, Kimberly Drew, Grace Dunham, Peter Eleey, Darby English, Okwui Enwezor, Awol Erizku, Teresita Fernández, Karen Finley, Hal Foster, Coco Fusco, Massimiliano Gioni, Alison Gingeras, RoseLee Goldberg, Claudia Gould, Thyrza Nichols Goodeve, Paul Ha, K8 Hardy, Steven P. Henry, Dave Hickey, Matthew Higgs, Laura Hoptman, Chrissie Iles, Jay Z, Rashid Johnson, Pepe Karmel, Jennifer Kidwell, Christopher Y. Lew, Kalup Linzy, Glenn Lowry, Jessica Lynne, Daniel J. Martinez, Steven Henry Madoff, Carrie Moyer, Jayson Musson, Shirin Neshat, Linda Norden, Catherine Opie, Clifford Owens, Ann Philbin, Lisa Phillips, Pope.L, Laura Raicovich, Taylor Renee, Kenya (Robinson), Jeanne Greenberg Rohatyn, David A Ross, Mera Rubell, Anne-Marie Russell, Antwaun Sargent, Joe Scanlan, Peter Schjeldahl, Carolee Schneemann, Jack Shainman, Shikeith, Lowery Stokes Sims, Lisa Spellman, Robert Storr, Ali Subotnick, Elisabeth Sussman, Martine Syms, Nato Thompson, Jack Tilton, Betty Tompkins, Mark Tribe, Eugenie Tsai, Pedro Vélez, Jorge Daniel Veneciano, and Joel Wachs.

*A version of this article appears in the April 18, 2016 issue of New York Magazine.