The 2016 Emmy race has begun, and Vulture will take a close look at the contenders until voting closes on June 27.

Who can blame Matt Servitto for thinking back often to his experience on The Sopranos? After all, he had the chance to spend several years appearing regularly — as Tony’s nemesis-cum-FBI insider, Agent Dwight Harris — on a series the 50-year-old actor says he and his fellow actors refer to simply as “The Show.” Eight years since its final episode aired, Servitto — enjoying a hot toddy spiked with Irish whiskey to complement his beet salad and smoked trout at Manhattan’s trendy Maysville bar-eatery — still tells time by the leather-strapped watch his late co-star James Gandolfini had engraved for him and the cast. And even as our conversation passes over numerous stops and starts across his 27-year onscreen career, it frequently wends its way back to HBO’s pioneering mob drama. On the topic of today’s oversaturation of scripted series, he nostalgically cites how The Sopranos singularly rallied viewers’ interest, and how on Monday mornings, he’d encounter people on the train who would shout at him, “What the hell was that bullshit? Where is the Russian?”

But in the blink of a decade, those days of watercooler common ground have given way to what Servitto himself describes as a “cultish” atmosphere surrounding even the most prestigious TV. It’s required that he and other character actors remain nimble and not too discouraged at some of the paradoxes therein.

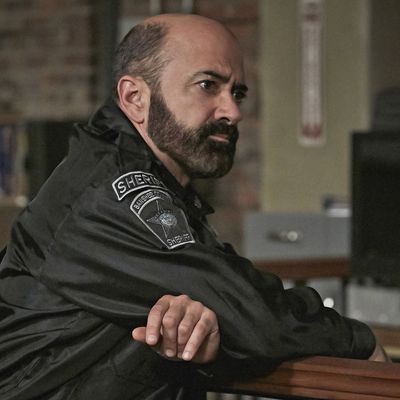

“As my agent says, ‘We’re all working twice as hard to make half the money,’” says Servitto, who now appears in a featured part as a small-town cop on Cinemax’s hyper-violent drama Banshee, which ends its four-season run tonight. Careful to avoid naming names, he shares, “I was talking to one actress, and she’s got like three recurring roles — a premium-cable show, a cable show, and a network show. That’s kind of the deal now.” What that boils down to in terms of dollars and cents for an ostensible freelancer is, as Servitto lays out, “They don’t want to contract you. They’ll give you a good recurring rate so you’re not beholden to them, they’re not beholden to you, and they’ll just check and see if you’re available and write story lines around it. So it’s an embarrassment of riches as far as the amount of work that is out there for the legitimate actor, but we all only have so much time. I don’t know what this explosion of content means.”

Some would argue that Servitto’s insinuated himself into the pop-culture consciousness nonetheless. And not just on account of his tenure as Agent Harris, but thanks to steady gigs on the big and small screen (in addition to occasional theater work), spanning from his start on soap opera All My Children circa 1989 up through Banshee and the devil incarnate on Adult Swim’s satirical Your Pretty Face Is Going to Hell. In between, there have been wide-ranging stints as a sketchy politician on Showtime’s fan-favorite crime saga Brotherhood; one-episode tours through Suits, Sex and the City, The Mentalist, Grey’s Anatomy, and myriad other prime-time shows; supporting roles in indie flicks like Woody Allen’s Melinda and Melinda and The Wrestler writer Robert Siegel’s Big Fan; not one, but three films under the directorship of infamous Cannon Films head Menahem Golan (“Menahem seemed to always find me at these financially vulnerable moments,” he laughs); and as the most irrefutable validation of his working-actor credentials, repeated turns as different characters on Law & Order.

“Instead of a SAG [Screen Actors Guild] card, every New York actor should have a Law & Order card,” he suggests. “That was the stamp of approval on your career. Then it was all about trying to complete the trifecta, cause you’ve done Law & Order, then they added SVU, then they added Criminal Intent. The thing that supports more hard-working actors in New York is [Law & Order creator] Dick Wolf.”

Servitto, who recently moved from Manhattan’s Upper West Side to suburban New Jersey with his wife and three children, says that more than just geography has isolated A-list opportunities. Shortly after breaking through on the soap-opera circuit, the handsomely featured Midwestern Italian upstart began losing his hair, all but dashing his leading-man aspirations overnight.

“All of a sudden, you look in a mirror in the makeup room, and you’re like, ‘What the hell? I can see the light shining through my hair,’” he explains. “It takes your breath away. And then you have to come to terms. Am I gonna try and hold on to this or start embracing it and shave my head a little bit?”

His mother actually offered to help pay for transplants, but Servitto immediately recognized his altered look was more blessing and curse. “I said to my mom, ‘Will you accept that the best thing to ever happen to my career was losing my hair?’” he recounts. “I looked very Italian with a full head of hair. It didn’t help that I had a bit of a mullet. But once it started to go, I looked like an Everyman. I could be Hispanic, Jewish, Italian … I just looked like a guy. I began to realize those smaller roles were far more interesting.”

His thinning hair availed him of what he describes as every drama-school student’s “delusion of, ‘I’m a leading man.’” (Unless, he clarifies, “that lead is a put-upon, frustrated, 40-year-old suburban dad.”) “There are moments in time where I look at number one on the call sheet of a TV show or movie and think, ‘Damn, that’s a lot of the work,’” he continues. “I don’t mind being number three, number five, very often getting the jokes, not having to carry the cross of the show on your back.”

Still, he concedes that, after Sopranos, there was a natural assumption that he’d rarely have to audition again, and superlative scripts would be beckoning for his involvement. To be sure, Servitto stayed busy, as his resume bears out, but for every Brotherhood, there was the necessary trade-off of ad campaigns for Campbell’s or NyQuil (he no longer does commercial work) to help support a growing family.

“There is the actor in me that feels like, ‘I’m on the iconic TV show. And now that’s in my back pocket,’” he says of his mindset after Sopranos wrapped in 2007. “You fall in the habit of checking your IMDb star meter. At the end of Sopranos, it rose higher than it ever had. You begin to want that currency to be cashed.”

Between his own personal cult renaissance via Your Pretty Face and Banshee’s final season, Servitto might finally be able to bank on that equity. Where his Banshee alter ego, Deputy Brock Lotus, has thus far by definition been second-in-command, and on the aforementioned call sheet, to Antony Starr’s Sheriff Lucas Hood, the final episodes put Brock — and Servitto — front and center. And after so much time somewhat out of focus, he’s more than ready for his close-up.

“It’s the best work I’ve done in television,” he declares. “We have such good writers, and they came to me at the beginning of this season and said, ‘We’re gonna funnel almost every story line through your eyes and let the audience see Banshee — both good and bad — through your character.’ Is that be careful what you wish for? No, man, I wanted that.” Though harkening back to the contemporary windfall of quality TV, he cautiously reiterates, “You just gotta hope people see it.”