In this age of superhero saturation at the box office, one of the unique delights of the X-Men franchise is its use of time: It considers it, it travels through it, it grapples with it. Ever since 2011’s soft reboot X-Men: First Class, each movie has taken place in a different decade: 1962 for First Class, 1973 for X-Men: Days of Future Past, and 1983 for last weekend’s X-Men: Apocalypse; naturally, the as-yet-untitled next episode will be set in the 1990s. Each film is filled with period-specific set pieces, references, and — often most delightfully — musical choices.

It makes sense that the X-Men movies would incorporate chronology more than any other super-series, as the X-Men comic books have a long history of time-hopping narratives. The X-mythos is filled with tales — many of them insanely convoluted — in which characters leap backward and forward in the timestream. Although they don’t age in real time (e.g. Cyclops was depicted as a teenager in his 1963, and comics today depict him as being somewhere in his late 30s or early 40s), theirs is still an intensely generational saga, filled with parents, children, and grandchildren. You don’t find that kind of stuff nearly as often in comics about other super-teams like the Avengers or the Justice League. There are a pair of reasons the X-Men archetype is so germane for stories about time travel — both in the sense of going into the far future or past and in the sense of just living through changes and seeing yourself grow old while younger people enter your life.

The first reason has to do with bigotry. The X-Men’s resistance to it is an essential part of the group’s history. Although the team has too often comprised a majority of straight, white characters, the struggles of this team of mutants — that is, humans with genetic abnormalities that grant them superpowers — have long reflected the struggles of real-life marginalized groups. It’s a blunt metaphor, but an effective one: Mainstream society finds mutants suspicious because they’re different and because of the actions of a few bad apples. “Sworn to protect a world that fears and hates them” is a phrase that repeatedly shows up in introductory text for X-stories, and that idea has been baked in since their earliest adventures.

When you tell stories that take place in the past and the future, you can talk frankly and depressingly about bigotry. Prejudice and hatred are as American as apple pie and as human as opposable thumbs. When the movies acknowledge the passage of time from era to era and show bigotry existing in the past, present, and future, it underscores how hard it is to crush. In the comics, we see it in the seminal 1982 story God Loves, Man Kills, where a hateful televangelist launches an anti-mutant campaign; we see it when his son picks up his father’s torch in a 2013 story in the series All-New X-Men. Time can perpetuate prejudice as much as it can diminish it.

Sure, many narratives can use time travel to talk about how racist, misogynist, and homophobic the world used to be by hopping to a particular era in the past — for recent examples, just look at the CW’s Legends of Tomorrow or Hulu’s 11/22/63. But the X-Men movies have a take that’s more sad in its comprehensiveness: We’ve seen tableaux of intolerance in the ‘60s, the ‘70s, the ‘80s, the ‘00s, and even 2023. Time after time, decade after decade, we see it persist. One of the primary X-characters, Magneto, is a Holocaust survivor, situating his views firmly in one of humanity’s historical nadirs — and in film and comics alike, he’s always there to point out that humans executed genocide not so long ago, and that they’re perfectly capable of doing something like it again. That’s the message: No matter how hard you fight, how many gains you make, there will always be more hills to climb in order to see a world free of discrimination. In an oft-overlooked X-Men mini-series, 1994’s The Adventures of Cyclops and Phoenix, we even see a discriminatory world millennia in the future. One of that story’s protagonists has kept the dream of the X-Men alive and translated the team name into the parlance of that era: Clan Askani, or “Family of Outsiders.”

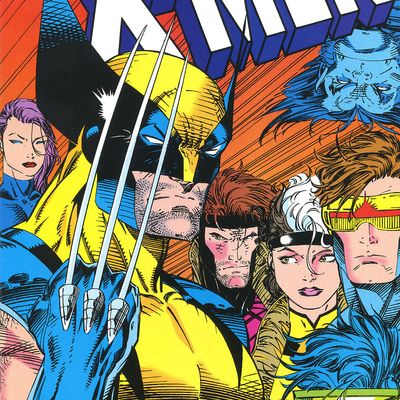

That concept of family — how it endures and how it shifts — is the other factor that makes time such a germane theme in the X-Men legendarium. Although the X-Men were originally formed as a group of teenage students learning to control their powers, what has kept readers coming back is the notion that the group is actually a kind of constructed family. As Andrew Wheeler of Comics Alliance put it a few years ago, the X-Men are not unlike a “house” in the queer drag scene: a makeshift family that, once joined, offers a safe haven from biological family members who look at you with fear, disgust, or confusion. You can find new parents who love you harder, more unconditionally than the people who actually gave birth to you. What’s more, there will always be young runaways and outcasts showing up to bring the house into the next generation.

But the families of the X-mythos are not just constructs — there are also families of birth. Most notably, you have the clan that centers around Scott Summers (a.k.a. Cyclops) and Jean Grey (a.k.a. Phoenix and Marvel Girl). The details of their family are baffling for someone who doesn’t obsess over comics (e.g. they have a daughter who was born in a possible future and came back in time; Scott had a child with a clone of Jean and that child was raised in the distant future before coming back older than Scott; Scott’s dad was presumed dead but actually ran away to space to become a cheerful pirate), but suffice it to say that much ink has been spilled over the ways that family’s various generations are formed, estranged, and reunited.

And what is family if not something that travels through time? Can you truly understand your significance if you don’t look backward in your bloodline to see the circumstances your forebears endured? Can you go through your life without making decisions about whether or not to have children, and if you do, what you’ll pass on to them for use in an uncertain future? There’s a potent scene in Apocalypse in which Michael Fassbender’s Magneto sings to his daughter — a Yiddish tune his parents and their parents had, and which he wants her to have. There’s nothing like that scene, where four generations are linked in one quiet moment, in, say, Deadpool or Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice, nor would it really make sense in either of them. But in an X-Men narrative, it feels perfect.

Of course, time travel and period pieces can lead to narrative problems. The timeline of the X-franchise movies is hopelessly screwed up at this point thanks to shifts in creators and creative direction. As Vulture’s Kyle Buchanan pointed out, the time jumps also mean Fassbender is, in defiance of all visual cues, supposed to be in his 50s in Apocalypse. And it’s even crazier in the comics. A few years ago, the present X-Men allied themselves with a team of past X-Men and future X-Men to fight an entirely separate team of future X-Men in one supremely insane crossover.

However, though the details may make you cock your eyebrows, the core idea stands: The X-Men mythos uses time to let us see the twin persistencies of bigotry and family with a vividness that one loses in sagas mired in an eternal present. It’s been true of the characters for decades; I can’t imagine it’ll disappear as we continue tumbling into the future.