“Can you believe I have a fucking pool?”

Walton Goggins is showing me the lush backyard of his 1922 French Tudor home in the Hollywood Hills on a hot June afternoon in Los Angeles. Even after living in the house for five years, he still can’t believe he actually lives here. “I mean, this pool was carved into the mountain,” says Goggins, whose lingering Georgia accent infuses every declaration with the earnestness of a Southern preacher. “I’ve been gone a lot lately, so anytime we’re all together as a family, we’re out here. It’s our own little paradise, you know?”

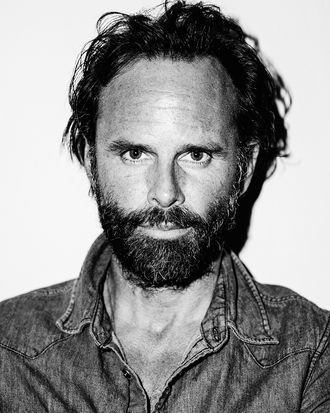

As Goggins takes our tour inside, we are greeted by his cherubic 5-year-old son, Augustus, and wife, writer-director Nadia Conners, who kisses Goggins newly bearded face — a makeover due to his upcoming role in History Channel’s Navy Seal drama Six, filming in North Carolina — before she rushes off to a meeting. “I wake up every morning with one of the smartest people I have ever met,” he gushes about Conners. “I have unfettered access to her brain; a very specific, all-encompassing worldview every single day. I’m truly the luckiest son of a bitch in Hollywood.”

To call him lucky in Hollywood would be to skip past the 25 years he’s spent playing That Guy. He logged countless supporting roles in indie films (The Apostle), studio movies (Cowboys & Aliens), and cable dramas (The Shield, Justified) before finding a crazy fan in Quentin Tarantino. The director shifted Goggins’s career into overdrive by casting him in 2012’s Django Unchained and in last year’s The Hateful Eight, telling Vulture last fall, “Watching him for six years [on Justified] do faux-Quentin dialogue let me know that he’s got the right kind of tongue.”

This week, Goggins, 45, returns to TV for his biggest (and most ridiculous) role yet in HBO’s latest entry from Eastbound & Down creators Danny McBride and Jody Hill, Vice Principals — an 18-episode, two-season comedy about two Southern high-school administrators, Lee and Neal (Goggins and McBride, respectively), who channel their loathing for each other into taking down the school principal. Goggins spoke with Vulture about how growing up poor and as an only child in the South led him to acting, how he fought his way into Hollywood, and why he “loves” Harvey Weinstein.

What appealed to you about HBO’s Vice Principals?

I truly think Danny McBride is Woody Allen for fly-over America. But Vice Principals isn’t as adolescent as Eastbound & Bound. But then again, remember the end of Eastbound’s first season when Kenny Powers leaves his girlfriend at the convenience store? Shit! Kenny is a fucking flawed human being. That’s why it all works. And Danny and Jody are always walking that line. I really believe what they do is sublime. Vice Principals also gets fucking dark. Dark and deep.

It’s also arguably the most over-the-top comedic material you’ve ever done. Is it a different exercise for you playing a part like this?

I actually feel like I’ve been doing comedy forever. The Shield was actually one of the funniest shows on television. Justified was another level of comedic intelligence. It was Elmore Leonard–sophisticated humor.

Elmore wrote the way we wish people really spoke.

Yeah, exactly. And Quentin does the same thing. His sense of humor feels like it can take place inside a bar or at the Met Museum. Similarly, Danny’s sense of humor is as adolescent as you can get, but when you look behind the curtain, there’s a lot going on. It’s extremely sophisticated.

How does it feel, after 25 years in Hollywood, to no longer be struggling or be seen only as “that Southern guy with the spiky hair?” I mean, you’re on Quentin Tarantino’s actor roster now.

It’s incredible, but mostly a total fucking relief not having to work so hard just to get a seat at the table. Playing Boyd Crowder [in Justified] was actually a real cross to bear for me personally; he was a real mantle I was carrying for a long time, and in order to rise above the stereotypical portrayal of Southern people as …

Rednecks and white trash.

Yeah. I’m proud of Boyd because I feel like I was able to educate people in urban areas about the struggles that people have in rural America. And then to have moments, like I did at Comic-Con for Django, where I’m sitting on the dais with Jamie Foxx, Christoph Waltz, Samuel L. Jackson, and just like, How the fuck did I get here? What is happening right now? I’ve had a lot of those in my career: “moments of manifestation,” I call them. Doing Shanghai Noon with Owen Wilson was one of those. Bottle Rocket was one of my favorite movies, and as soon as I saw it I thought, “I’m just gonna focus on this dude. I want to work with this guy.” And I did.

So Bottle Rocket comes out in 1996 while you’re in L.A. still looking for your big break as an actor. How did you pay the bills?

Well, first I refused to work in a restaurant. [Laughs.] Nothing against waiters and waitresses, but I couldn’t do it. I didn’t want to be that actor in L.A. having conversations with other actors about acting. I usually run away from those things. I generally don’t hang out with actors in between takes. I’m an only child, so I’ve always been off in a corner somewhere. I think it’s actually taken some learning to know how to be around other people. But the one thing I never had a problem with was listening. My mother was a great listener. And so I never had to compete for her attention because I was an only child.

What did your parents do for work when you were growing up?

My mother made $12,000 a year working for the State of Georgia in Workers Comp. My father sold insurance. But my parents divorced when I was 3. He and I had an on-off relationship for most of my life. So growing up it was me, my mom, and father’s father, oddly enough. He was the one consistent male figure in my life. I was the apple of his eye. I was mostly raised by extraordinary, highly dysfunctional, crazy Southern women. My mother’s mother was an actress in New Orleans in the 1930s. She met my grandfather and moved to Warm Springs, Georgia, and he was good friends with Franklin Delano Roosevelt. He had a thousand acres growing peaches and pulpwood. They had this beautiful life, and my mother and her three sisters were born into it. My mother remembers Roosevelt stopping in the yard saying, “Hiya, neighbor!” Then they went from this incredible cultured bucolic life to my grandfather dying from diabetes in my mother’s arms when she was 14. Then the house burned down, my grandmother went insane. She was a nurse and got addicted to amphetamines because of the grief of losing her husband and raising four girls ages 4 to 17. It’s a passel of amazing fucking stories. I had a front row seat to the real Steel Magnolias. But we were all fucking black sheep.

Who first introduced to you to the arts and performing?

Another aunt of mine wound up being a publicist for B.B. King, Phyllis Diller, and Wolfman Jack. But because my mom had me when she was 23, after they had lost everything, all we really had arts-wise was a lot of storytelling. Our family time was never about TV or cinema. And a whole bunch of her friends were always stopping by. There was a dude named Rabbit who was a locksmith and a small-time pot dealer who’d park his van in our yard, open our windows, and use our electricity to make his keys. Another dude named Be-Bop was also always there. He gave me my first job —selling hope chests for young girls who wanted to get married. [Laughs.]

Did you act at all in high school?

No, but I grew up watching another aunt perform on stage from the time I was 6. I stayed with her while she was doing dinner theater, and I’d see these beautiful women changing backstage, the whole life, the bohemian lifestyle, the reaction from the audience and thought, “I want to do that. It’s very powerful.” So I went to this casting director’s office in Atlanta, a woman named Chez Griffin — I didn’t have an appointment, so my mother drove me down there, I was only 14 — and I knocked on her door and said, “I want to talk to Chez. My name is Walton Sanders Goggins Jr. I don’t need an appointment. Just tell her.” And she came out and said, “Okay, who is this kid?” I told her, “I don’t know how to do this, but I know that I’ve had an interesting life, and I know that I feel things deeply. With some guidance and help, I can do this.” And she said okay. Then I started working in Georgia, and did a movie in 1990 called Murder in Mississippi.

Did you consider college at all?

I went to Georgia Southern for one year. I had good grades and probably would have gone into philosophy or political science. I was also really good at math. I had a good memory if nothing else. I think it helped that growing up I was given a lot of responsibility. I was a latchkey kid. I’d get home after school when I was 7 and be left alone until my mother got home. That was life in 1970s, man. She’d call me, “Did you make it home? Are you still alive? What are you gonna have to eat? Okay, I’ll be home at six.”

Can you imagine doing that with your kid now?

No. I was only two fucking years older than my son is now!

So you leave college and move to L.A. at age 19 by yourself. That must have been very difficult and isolating.

Yeah, it was. But I actually got my first job after being here for one week — a role opposite Billy Crystal in Mr. Saturday Night. I was the Nervous Kid in a flashback sequence. It didn’t make the movie, but it made the DVD. [Laughs.] That was a really big deal. I actually ran into Billy about three years ago. I wasn’t gonna say anything, but he looked at me and said, “You’re not so nervous anymore!” But even getting a role to play a role like “Guard at the Gate” was a struggle. I worked a lot at night, too. I had a valet parking business. I had six restaurants and three parking garages as clients in the Valley — places like the Moonlight Tango Café, the Great Greek, and Cha Cha Cha. I also sold cowboy boots. Around that time I got a part in The Next Karate Kid with Hilary Swank. I was twenty-fucking-one years old and the main bad-guy part was down to me and a guy named Michael Cavalieri. So I went in first, and nailed it. It was like, Wow, my life’s about to change! I’m the bad guy in Karate Kid! Everyone’s gonna know who I am. This is real work! And then he got the part.

That knocked you down a peg.

Yeah. I told myself, “Don’t cry in front of these people. Hold it together, walk off this lot right now.” And on my way out, I walked passed Warren Beatty. I had tears in my eyes and he looked right at me; I’m sure he could tell what was happening. He nodded kindly and kept walking. It was like he knew, you know? So I go back to my boot-selling job on Pico. I’m helping somebody find a size 10 and I’m like, “You know what, man? Fuck this!” I pick up the phone and call Warner Brothers and say, “I need [late producer] Jerry Weintraub’s office.” The director Chris Cain picks up the phone and I tell him, “I understand why I didn’t get the part. But the character has a best friend. I’m calling to see if I could audition for that part. I just want to learn from you.” He says, “Hold on a second. Jerry!” He comes back and says, “Okay, the job’s yours.” And I was with Hillary in Boston for four months and made $21,000 — more money than my mother made in two fucking years. And I continued to work pretty steadily until I got The Apostle three years later and was able to quit all my other jobs.

Your most significant creative relationship has been with fellow Southerner and creator of Rectify, Ray McKinnon, an actor-writer-director with whom you’ve made numerous films and won an Oscar for the short film The Accountant. When did you first meet?

On Murder in Mississippi. He played my father, even though we are only 15 years apart [laughs]. I remember walking into the table read and sitting right next to him, which made sense because he was playing my father. And the first thing he says is, “Don’t sit near me. You need to sit somewhere else.” He told me later, “I don’t look old enough to play your father and if you sat next to me, they’d see that I wasn’t old enough to play your father and they’d fire me.” But actually 15 isn’t far stretch from where I come from to have kids. I’ve got a couple of buddies at home who had kids at that age! Years later, we decided to be partners. And we became very close. I love him like a brother. The short film and movies we’ve made I’m as proud of as anything I’ve ever done. We are now 26 years into our friendship. He’s the first person I call in a crisis.

Did you see an immediate boost in acting opportunities after working alongside Billy Bob Thornton and Robert Duvall in The Apostle in 1998?

Yes and no. I remember being at the Toronto Film Festival and people whispering in my ear, “Man, this movie is going to change your life. This is it!” And then after it came out, everybody thought that I was just a local hire from Louisiana, so it didn’t do shit. [Laughs.] But when I was 29, The Shield comes along. And even then I was almost vomiting thinking, “I don’t want to get fired, please don’t let me get fired.” And the execs did want to fucking fire me after they watched the pilot! They were like, “This guy’s just fucking annoying.” I only had four words in the pilot! [Laughs.] But [creator] Shawn Ryan, unbeknownst to me, told them, “Give me one more episode with this guy.” And episode two was all Shane, my character, and Vic [Michael Chiklis]. Then they said, “Okay, never mind. He’s the guy.”

Since 2012, you’ve appeared in two Tarantino movies, Django Unchained and The Hateful Eight. What have you learned from him about storytelling?

He’s an analog storyteller. His approach to the work is a confirmation to me that, no matter what, the story is king. And you are in the service of story regardless of how fucking difficult it is. Quentin enjoys the entire process. He brings you into the history of film and contextualizes your place in it. We are not singular in this expression, but we’re a part of one of the greatest inventions of human history.

And he is becoming increasingly more singular in his approach to making movies.

Yeah, it’s him, Paul Thomas Anderson, and a few others.

Sadly, women directors are never credited with having the same impact on the craft.

Yeah, and that’s fucking crazy. One of my directors on Six is Lesli Linka Glatter. She’s a baller, man. She’s on par with the best directors I’ve ever worked with. Also on the show was Kimberly Peirce. She is an artist. She’s intense. I also want to throw Gwyneth Horder Payton’s name in there. She was first AD on The Shield for six years and is now running her own shows.

From an acting perspective, what are the distinct differences you see in having a woman director?

Having been raised by women, I understand them. Unless I’m in a relationship with them, and then I don’t have a clue, man. [Laughs.] But the biggest difference is their ability to process stress. They are usually more even-tempered. They are as aggressive as men when they need to be, but generally more accessible. And the ego doesn’t seem to be as prevalent. It’s a really nice energy to be around. There is just this fucking evenness to the day when a woman is at the helm, like Buddhist directors. I’ve worked with some of those, too!

Six is an ambitious project for History. What made you say yes?

Well, Harvey and Bob Weinstein are producing it. I love Harvey.

What do you love about him?

We’ve all heard Harvey stories, you know? [Laughs.] I got to know him well over the course making Django, but was still extremely intimidated by him. He walks in a room and sucks the air out because he’s fucking Harvey Weinstein. And thank God a person like him still exists in the world. An authentic, larger-than-life personality, which are slowly being weeded out of Hollywood. We’re all so fucking marginalized now. But I told them, I’m not going be used as a propaganda for the American military. I have my own views, which are very level-headed. I’m not anti-military. I am in a place in my life where I am not really anti-anything.

Are you anti-Trump?

[Pauses.] Yes, I am. I am fucking anti–Donald Trump 100 percent. So I said if I do the series, I want to be sure both sides are equally represented. You honor the person that is asked to fight and then talk about what that does to them spiritually and psychologically and emotionally. That’s why I got involved. And they have lived up to my expectations. I’m excited because I think it’s gonna poke people with a sharp stick on both sides of the conversation.

How would you describe your relationship with fame? Are you able to enjoy it?

[Laughs.] Well, I’ve gotten to a place in the last four or five years where people actually know I’m Walton Goggins.

And not Walter Goggins as you’ve been called many times.

No, not Walter. Except at Starbucks [laughs]. Come on people, it’s very easy, Walton. Walton. But if people see me on street, and they care, they think, “Yep, I’m talking to that guy. Hey, man, love your stuff. I want to talk to you about shit!” Unless I’m with my kid, I’m like, “Let’s do it!” I like that I’m a dude people want to talk to. There will be a time and when the acting part of my life over. I’ll live in another country and do something completely different, whatever that is. But for now I am having the time of my life. And there’s no pressure, because I don’t need to be Brad Pitt!

And Brad doesn’t even need to be Brad Pitt anymore. He probably just wants to get fat and lazy and lay around the house.

[Laughs.] Exactly. I just want to just tell good stories, aggregate all the fucking cool friends that I’ve made along the way, drink some wine, work really, really hard and be a great father and a good husband — at least 60 percent of the time.

This interview has been edited and condensed.