Remember when Taylor Swift wasn’t a villain?

It’s hard to imagine now, after a week that saw her go up against Kimye and seemingly confirm every bad feeling you may have had about her, but as recently as two years ago, a lot of smart, progressive people were on her side. Glamour once cheered her for “making too cool uncool,” while the Times dubbed 2014 “The Year of Taylor Swift.” You can still find hints of this vanished era if you stumble through old blog posts — we once lived in a world where it was generally accepted that Swift was a kind, genuine person.

Now, though? Now a site can publish a roundtable called “When Did You First Realize Taylor Swift Was Lying to You?” and it’s among the nicer Swift takes. When did the media turn on the woman who, for a brief, shining moment, was one of the chattering class’s most beloved pop stars? That’s what we’re here today to find out.

(Caveat: When we talk about the media, we’re mostly talking about the think-piecing-coastal-elites media. The mainstream tabloid media — People, Us Weekly, etc. — has always been Team Taylor.)

Swift didn’t start out in our good graces, of course. She had to work to get there. Even though she hailed from suburban Pennsylvania, she read as culturally “red” at first, with those fiddles, Southern vowels, and heteronormative fantasies of romantic bliss. You didn’t have to look too deeply into her early work to find a conservative streak: “Fifteen” was sex-negative; “Picture to Burn” contained an unfortunate gay joke. In 2009, Sady Doyle wrote the canonical hit piece, dubbing the “You Belong With Me” video “a triumph of girl-on-girl sexism,” and slamming Swift’s “cartoonishly innocent and pure … blonde blue-eyed white girl thing [which] strikes me as just as artificial and calculated as any other pop star’s personal brand, with an added noxiousness due to its edge of moral superiority and ‘50’s-style coy submissiveness.”

Her third album, 2010’s Speak Now, did little to turn things around. “Better Than Revenge” only solidified the idea of Swift as a slut-shamer who didn’t support other women, and her performance of “Innocent” at the 2010 VMAs, which opened with a replay of the Kanye West incident of the previous year, gave the vibe of someone who was a little too comfortable painting herself as the victim of an angry black man. Coupled with the Surprise Face meme, Swift’s star image acquired a sour subtext: She was cold, calculating, fake.

The release of Red in 2012 saw Taylor nab her first No. 1 single and ascend into the upper echelon of the A-list. She wore a lot of bright patriotic colors during this period, and had recently dated a Kennedy; to many, she seemed the musical embodiment of American hegemony — an aircraft carrier in high-waisted shorts. As Foster Kamer and Ernest Baker explained in Complex: “Neither you, nor the charts, nor any man, woman, or mortal being will ever stand in her way. It’s not a terrible thing, or a great thing. It’s just a fact, like gravity … She wasn’t built to lose, in the same way Goldman Sachs wasn’t built to lose, either.”

The Red promo tour saw Swift give a classic nonanswer to the obligatory are-you-a-feminist question (“I don’t really think about things as guys versus girls”), but it also saw the seeds of her eventual transformation. That fall, Swift began a public friendship with Lena Duham — about as “blue” a celebrity as you can get — and the Girls creator soon provided a strong defense of Swift to Vulture: “Anyone who thinks Taylor Swift isn’t good for the girl cause has to be crazy, because any woman who’s dominating the charts, the creative director of her own empire, and made whatever millions of dollars last year is only lifting us up.” This was a very specific version of feminism, but it was a version of feminism nonetheless.

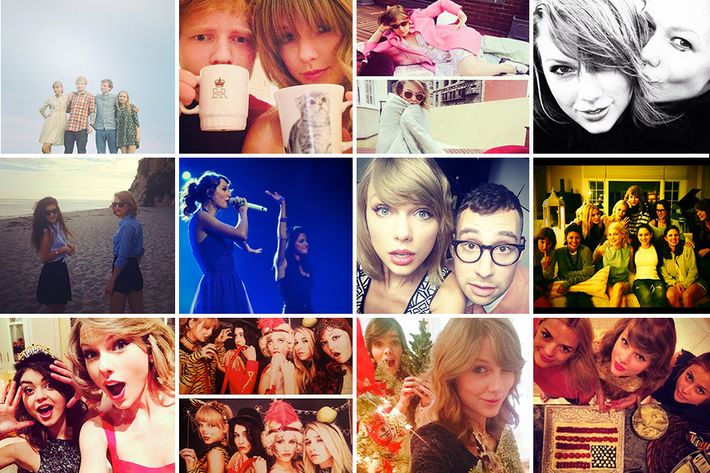

Over the next two years, Swift made a series of major life changes. In spring 2014, she moved to New York City. She joined Tumblr, and started lurking in her fans’ social media. She became friends with people like Tavi, Lorde, and Jack Antonoff. She called out the press for focusing too much on her relationships with men, and gave quotes about the importance of female friendship. In an interview with The Guardian, she came out as a feminist. A charitable read is that Swift was simply growing as a person as she entered her mid-20s. A more cynical outlook is that, in the words of BuzzFeed’s Anne Helen Petersen, she was employing “an incredibly savvy image maintenance strategy.” These interpretations are not mutually exclusive.

Whatever her intentions, the reactions to Swift’s transformation were effusive. (So effusive, in fact, that she was largely able to shake off her first racial-appropriation scandal.) She became one of the few people to ever appear on both the cover of Time and the cover of Maxim, discussing sisterhood and solidarity in both. SNL made a sketch about the feeling of vertigo that came from realizing you enjoyed a Taylor Swift song. Vulture published so many stories about her — including a glossary and a walking tour, both of which I contributed to — that commenters were on the verge of open rebellion. The Guardian mocked the enthusiastic reception to the “Blank Space” video with a post titled, “How Taylor Swift’s ‘Blank Space’ video redefines music, politics and everything else ever,” and that faux-hyperbolic take was just barely an exaggeration of the paper’s actual one. At year’s end, Mic, usually a reliable indicator of the way the progressive wind is blowing, found “9 Times Taylor Swift Was Right About Feminism in 2014.” Through sheer force of effort, Swift had managed to will herself a new identity as a feminist fairy godmother.

Of course, as any woman can tell you, the moment you call yourself a feminist is only setting up the moment you’ll be called a bad feminist. Over the course of 2015, Swift managed to lose much of the goodwill she’d built up in the press. How? It came down to three things:

1. Overexposure

Swift kicked off her 1989 World Tour in the summer of 2015 with a central gimmick: To cement the theme of female friendship, the shows would often see Swift “welcome to the stage” a surprise guest — sometimes one woman, sometimes many women — whom, it was implied, Swift personally admired. (Men were occasionally invited too, especially if they had a hit single Swift could perform.) The content industry’s interest in a topic dries up only when the page views do, so these appearances earned a hefty dose of coverage — which meant that Swift and her suddenly ubiquitous “squad” were in the news every time she made another tour stop. Oh, and the tour lasted six months.

2. The complicated legacy of “White Feminism”

It’s increasingly popular to use celebrities as signposts (or, as Roxane Gay puts it, “brand ambassadors”) for various strains of political thought; an informed observer can now pinpoint all the ways “Tina Fey feminism” is different from “Beyoncé feminism.” This development has been very beneficial for the media — entertainment news spreads better when injected with a dose of political signaling, and potentially abstract political discussions spread better if they’re attached to a recognizable name — and for an artist, there can be definite benefits in having your work linked with a specific politics. But the risks are heightened, too: Your failings become not just the failings of a person, but the failings of an ideology, and must be denounced even more loudly.

As the think pieces about Swift, her “squad,” and feminism piled up, a few writers ran contrary to the hyperbole. At Gawker, Dayna Evans wrote the first major takedown of Swift’s YAAS-QUEEN era. (Full disclosure: Evans, a staff writer for the Cut, is now my New York co-worker.) In a concert review titled “Taylor Swift Is Not Your Friend,” Evans wrote:

To think of [Swift] as womanhood incarnate is to trick oneself into forgetting about “Bad Blood” and “Better Than Revenge.”

Swift isn’t here to help women — she’s here to make bank. Seeing her on stage cavorting with World Cup winners and supermodels was not a win for feminism, but a win for Taylor Swift. Her plan — to be as famous and as rich as she can possibly be — is working, and by using other women as tools of her self-promotion, she is distilling feminism for her own benefit.

In some ways, this was a repeat of the old criticism of Swift as a creature of calculated self-interest. But because she had been so successful at politicizing her image, the critique was politicized as well: Swift became an embodiment of “white feminism,” a brand of progressivism that centers wealthy white women at the expense of everyone else. (Like a hipster or a neoliberal, no one identifies as a white feminist.) Critics soon fell over themselves pointing out that Swift’s clique was really just an exclusive group of mostly white actresses and supermodels. As Mic now put it, Swift’s #squadgoals were “totally disturbing.”

3. The feud with Nicki Minaj

That line of critique might have been too abstract to catch on … until Swift made it painfully concrete in July 2015 by getting into a Twitter spat with Nicki Minaj over the VMA nominations. Once again, Swift tried to paint herself as a victim of a black artist, and this time, she was clearly in the wrong; in the words of The Guardian’s Nosheen Iqbal, Swift was “at best patronizing and ignorant; at worst vacuous and self-absorbed.”

The negative reading of Swift, that she was another white woman whose feminism didn’t extend past her own front door, was widely embraced as the correct one. She eventually apologized — a rare sight — but the damage had already been done. By the fall, Aaron Bady was calling the “Wildest Dreams” video “nostalgic for a time when you could be nostalgic for white supremacy.” Not too long after, even Bustle was writing lists of “5 Important Reasons I Can’t Love Taylor Swift Anymore.”

Swift was savvy enough to catch the mood in the air. “I think people might need a break from me,” she told NME in October of last year, floating the idea of taking time off after the conclusion of the tour. This didn’t happen: West dropped “Famous” four months later, which thrust the spotlight back on Swift. The drama basically hasn’t let up from there.

At times Swift seems to be replaying a darker version of the Speak Now era: Instead of a possibly-fake relationship with Jake Gyllenhaal, there’s a probably-fake relationship with Tom Hiddleston; instead of a vague sense of Swift controlling events to make herself the victim, there’s actual video proof. Now, even a relatively innocuous story about songwriting credits somehow carries a sinister air. The seemingly impossible has happened: Swift experienced a very public invasion of privacy, and basically no one was on her side. Having been manipulated into loving Taylor once, the media swears, it won’t be fooled again.